Abstract

The article is the expression of new approaches that nationally and internationally are emerging about the themes of the Environment and the Territory, with a peculiar focus on the cultural heritage and on the value of the political institutions represented by the Municipalities. Moving from the metaphor of “bone and flesh areas” the article analyzes the abandon process that are experiencing Italian inner areas. In this paper, we also propose a re-birth of these areas, criticizing the dismantling policies of the institutional fabric, which could provoke a crisis for the territorial democracy and for the inner areas development.

“Areas in the bone” is not just a quote: it is the metaphor of the load bearing structure of Italy as well as the plastic representation of the marginalization process of the inner areas of the country that started from XX.

In 1958, Manlio Rossi-Doria, coined the expression “flesh and bone” in order to underline the profound socio-economical feet apart among the numerous inner areas and the few valleys. His analysis coming from his specialization in agricultural economics was focused on the southern agricultural sector, in a historical phase in which were visible the firsts effects of the Riforma Agraria (Agrarian Reform) and of the investments of the Cassa del Mezzogiorno (Fund for the South) started since 1950. The interpretative framework developed by Rossi Doria can be extended to the entire peninsula, where the differences between urban and rural areas, inner territories or the coasts, mountains and valley grew more and more.

Inner areas have experienced a deviation whose principal effects are the depopulation, the emigration, the social and economic rarefaction, the abandon of the soil and the landscape modification.

The setting up of protected areas, the economic and social effects of the tourism and other small local economies have only partially contained, from north to south, a centuries old process that builds in the Italian territory a big peripheral area that acts as a counterpart the phenomena of urbanization and of construction of more attractive littoral zones.

Mountains, inner little hills, and the secondary valley floors have been the sacrificial victims of contemporary economic development, inexorably damaged also on the environmental level: from the hydrogeological vulnerability to the landscapes transformations, from the runaway re-naturalization to the anthropic value losses (human settlements and historic infrastructures).

This has been a national process of the wider processes of “miseria dello sviluppo” (the misery of the development) and of the “grande saccheggio” (the great ransack), using the titles of two books that the historian Piero Bevilacqua wrote to criticize the global capitalistic model.

In the current phase of structural economic crisis of this development model, that have focused the economic interventions in the “flesh areas” and relegated the inner territories, mostly rural and/or agro-forestry and pastoral areas, in a marginal position, starting to study these “bones areas” can open a new way to the renaissance. In this perspective, it is very important to implement pragmatic solutions in order to provide new development frameworks in a wider sense.

In a perspective of territorialization of the policies, meaning with this expression the building up of a new politics less “abstract” and more place-oriented there are four main pillars for the rebirth of inner areas:

1) The preservation of territory and the safeguard of its inhabitants by entrusting to them the management and the care of the territory itself;

2) The Promotion of the natural and cultural diversity by creating a polycentric culture through open networks;

3) The identification of underused economic resources in order to promote the labor market;

4) The Empowerment of the institutional network represented by little municipalities and territorial institutions.

The birth of the Società dei Territorialisti (2011) and the structural re-organization of the University have allowed new multi-disciplinary research experiences on territorial development. These experiences represent a necessary cultural shift that focuses on categories such as “local” and “territory”, underlining the essential role of these categories for both the theoretical and practical frameworks in defining the relationship among the different territorial elements (cities, rural and urban areas, etc.) and its non- dissipative usage.

Starting from the idea of territory as a common, it emerges the value of small municipalities and the local public institutions in a cooperation perspective. These municipalities, that represent almost the totality of the 8000 Italian municipalities, are called “small” but they often are “big” both for territorial extension and for the economic and cultural resources that effectively or potentially they own within their boundaries.

Above all, it is the bone area that preserves a great part of the Italian Cultural Heritage: an interesting mix of products, story, identity, wellbeing and environmental resources. During the second postwar period, numerous intellectuals, with differents academic and professional backgrounds such as Italo Calvino, Antonio Cederna, Mario Soldati, Aldo Sestini, Luigi Veronelli, Cesare Zavattini, focused on the importance of these territories but their warnings remained unheeded.Landscape in this vision represents the apical resource such it has been defined.

A unity of resources and goods whose preservation is ratified in the 9th article of the Constitution of Italian Republic, inserting among the Fundamental Principles of Italian Republic the Preservation and Valorization of the historic and Artistic Heritage of the Nation. The article number 5 affirms the important role of local autonomies and imposes to the Republic to “accord the principles and methods of its legislation to the requirements of autonomy and decentralization”.

In 1947, Constituents, thinking to the long civic tradition of the Comuni (comunes) and taking into account the precedent law making experiences in the field of preservation, included the need to preserve and valorize arts and landscape heritages in the principles that had should inspired the future policies of the Italian Nation.

Today there is the need to reaffirm, to teach and to disseminate the beauty and the value of the Italian territory in its whole, and to revitalize the basic institutional framework. These aspects of territorial development have been overlooked during the past decades while the attention was focused on short-sighted policies and speculative investments.

Salvatore Settis wrote that we are dealing with a sense of displacement, meaning with this expression that we are both losing our orientation and losing our “places”. “Displaced” is also the title of a beautiful book wrote by Antonella Tarpino that analyzes the “abandon places”. Franco Arminio , more poetically, talks about a sort of an abandon and desolation geography while Giuseppe Dematteis invite us to understand the dynamics of a possible rebirth of the mountain areas.

These local territories, with their institutional profiles basically founded on the tradition of the Comune, represent also the primary and basic level of the democracy and of the political representation. The Comune is the central element of a strong Italian civic tradition that starts in the Middle Ages and arrives to the Republican Constitution, going through Carlo Cattaneo, which considered the Comuni, and above all the small and well functioning Comuni, the backbone of the entire Nation. Standing to Cattaneo, whose federalism theory was nowhere near to the interpretation of the Lega and its leaders Umberto Bossi and Matteo Salvini, the federalism policy founds on the municipal self-governance, in a vision in which the small municipalities represent a “nervous plexus of the neighborhood life”.

The Intellectuals of the Risorgimento, suggesting a relationship between the local self-governance and the quality of life, underlined that in Lombardy there were both a general high-standard of living and the greatest number of small and micro municipalities (with less than 1000 inhabitants). Lombardy was, standing to Cattaneo, the Italian region with the higher number of infrastructure, schools, doctors, and with “every other municipal benediction”.

Nowadays, the reading of the words of Carlo Cattaneo could be useful for many detractors of the small municipalities, as well as the supporters of the small municipalities unification, and among them numerous men of government, such as Renzi and Berlusconi, and paradoxically, even some local mayors and public administrators.

In the wave of this historical tradition, during the last 25 years there have been developed profound and seesawing transformations, which have created hopes and disillusions, mixing in schizophrenic way the debate about the federalism theory and the critics to the local autonomies.

Law changes of the last decade represented a regression of the local institution as local economic development agents and as basic expression of the democratic system. During the 90s local governments knew a fruitful transformation phase, with the law on local autonomies (142/1990), with the law on the direct election of the mayors (81/1993) and with the so called “Bassanini Reforms” (1997/1998) on the decentralization of the administrative functions and on the bureaucratic simplification. As a result of these reforms, the municipalities developed the so called “identity associations”, namely thematic associations of municipalities often linked with a traditional product or a distinctive cultural heritage: Wine cities, Olive oil Cities, Pottery Cities, Truffle Cities, Slow Cities and so on.

Later things changed and nowadays it seems long gone the era of the ambition of the local administrators to be the main actors of a local economic development. 90s have been a period of the relaunch of the municipalities, but the later decade has been a regression period, and the difficulties experienced by the small municipalities have grown year after year. Difficulties that have made harder for the municipalities the tasks of territorial promotion, of local development and of preservation and valorization of the huge cultural heritage scattered on their territories.

It seems long gone also the Mayors’ era, namely the phase in which, as a response to the Mani Pulite’s bumps, the local administrators were the point of reference for the municipal and community government, as well as the symbol of a changing Italy, provoking a widespread discomfort within the mayor national parties, whose interest was to lead the innovation back into old frameworks, in order to maintain the comforting status quo.

Also In this phase, there were some mayors that started their political career obtaining good results, but later they’ve been, willy nilly, main actors of this regression trend.

In 1997, with the aim of analyzing the difficulties and the contradiction between new mayors and traditional parties, Maurizio Vandelli, an administrative legal expert, wrote its book Sindaci e miti (Mayors and Miths), with the evocative subtitle Sisifo, Tantalo e Damocle nel governo locale. (Sisyphus, Tantalus and Damocles in local government). The book described the new local administrators, often foreign to the professional politics, where living their work experiences with struggles, frustration and uncertainties.

Another book, La Repubblica delle Città (The Cities’ Republic), by Antonio Bassolino, was published a year earlier, in 1996. The centrality of the Comune is here connected with the Italian history; in the thought of Bassolino, on the wave of the enthusiasm due to the redemption of a complicated city such as Naples, It is needed to pivot on cities and small municipalities because they are the nearest institutions for the citizenship: “We are our cities, but we need to start again in believing it”.

The 90s ended with the book wrote by Vincenzo De Luca, elected in 1993 as Salerno’s mayor, leading a progressive City Council foreign to the traditional parties. The book deals with the issue of public administration and its relationship with the citizenship, by combating the bureaucratic morass that prevents the modernization of the Country, particularly for the South.

Many hopes was been invested in the mayors direct election mechanism. Instead, the new mechanism turned out to be an illusion, an opportunity missed because of the strengthening of Central Governments and the losses of importance of City Councils and Committees. “A deserted revolution”, as defined by Gaetano Sateriale, Mayor of the city of Ferrara from 1999 to 2009.

Nowadays the Comuni seems crushed in their double historical function (local government and democratic delegation) and they’re experiencing difficulties even in the management of their core tasks, namely to supply services to the citizen.

Somebody talked about their unification, in order to demolish the system of the local autonomies, that are the institutions that really manage the territory, that care for its integrity and its resources, the institutions that represent the basic scheme of the democratic system. It has also been proposed to demolish the mountain communities, to the abrogation of the Provinces, and the recent proposal to eliminate the State Forestry Corps.

Nevertheless, and specially in small municipalities, the city council and the mayor still represent the point of reference for the citizenship, as it is demonstrated by numerous experiences of different municipalities situated in the bone area, which represent significant experiences of territorial development, monitored by the Italian Observatory of the Territorialists’ Society.

It is needed a mapping of good practices and of the possibility of an economic, social and territorial regeneration. A benchmark process with a focus on the landscapes of the inner areas, seen as a whole and inserted in the ecosystem of the relationships between cities and rural areas that characterizes the overall Italian History and that is a focal point in the global/local dynamic.

This map of virtuous experiences and possible rebirths should be the basic tool in order to strengthen the progressive weakening process of local institutions. In our mind the role of the Municipalities is still very important, and it anticipates a sort of neo-municipalism without any parochialism. This neo-municipalism could renew the democratic participation processes through a rediscovered local representation, which should be able to combine the political issues and some fundamental themes (territory, economy, culture, environment e resource management, public spaces and services, commons…)

The general attacked launched towards the municipal autonomy and towards the role of the small municipalities, represents one of the main problems of our time, threatening cultural heritage, economic resources and civic tradition.

In the last phase of this “attack” (2011-2012), the implementation of national laws about the containment of public spending, and the consequent regional laws, worsen the equilibrium of many municipalities, strengthening the risks of loss the local autonomies’ system, on which is based the Constitutional Structure of the Italian Republic.

By the effect of these laws, many municipalities have disappeared, particularly in Tuscany and in Emilia Romagna, as said in the very Italian central territory, which has been for long time the cradle of the municipal civilization.

The alarm bells sounded in many territory of Italy, in rural territories with lots of traditions and where the is an huge heritage in terms of agro-environmental, craftsmanship and touristic resources. The process started with the initiative of Regions, or, in other cases, with the Mayors themselves, which, on the wave of public economic incentives, deliberated the start of an administrative fusion path.

It surprised that Tuscany joined this initiative: among the greatest Italian regions, Tuscany has the smallest number of municipalities (less of 300 while Lombardy counts more of 1500 and Piedmont more than 1200).

This process is now, fortunately at a standstill, after the citizenship, through the referendum tool, rejected numerous proposals of municipalities’ merger, causing in some occasions the change of the city council.

The structure of Comune, intended as above described, has medieval origins. During the modern age, its development process joined the evolution of National Countries, grew up by holding out against the bureaucratization and centralization processes, until it has been fully acknowledged by the legitimization within national constitutions.

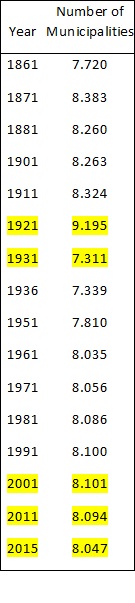

As the table shows, the number of municipalities has always had a positive trend, except for the periods in which there has been totalitarian government (in the table there are underlined the regression periods):

During the XVIII, in Tuscany, during the Grand Duchy of Pietro Leopoldo, an authoritarian public system, numerous municipalities have been merged and there have been a strong reduction of the total number of municipalities.

Similarly, in Italy, the Fascist Measures taken between the 1927 and the 1929 reduced the number of municipalities and reformed the provincial administration. Mussolini himself wanted a reduction of the number of municipalities: in 1927, during its well known Discorso dell’Ascensione, he said: “9000 municipalities are too much. There are municipalities with only 200,300,400 citizens. They can’t live, they have to live with the idea of disappear, and merger themselves with bigger centers.

Actually, a brief analysis on other European Countries does not confirm the idea that 9000 municipalities are so numerous: France counts almost 36500 municipalities, Spain more than 8000 and Germany more than 12000 on an area that is just a little bigger than the Italy.

This evidence is still valid if we make a ratio between the number of municipalities and the total citizenship: In Italy there is a municipality every 7500 citizens, in Germany every 7200, in Spain every 5600 and in France there is a municipality every 1700 citizens. European Union counts a municipal district every 4.100 inhabitants.

Dismantling the municipalities and depriving small centers of the institutions represents a wound in the democratic system and it contrasts with the need of a socio-economic re-development of inner areas. Fabrizio Barca, already Italian Minister for the Territorial Cohesion, has the same opinion: in one of his recent work papers, he affirms that the evaluation of inner areas is one of the strategic options in a perspective of a necessary territorial-led development policy addressed to the places.

Fortunately, there are also signals that benefits small local realities, as the plea addressed to the Government and to the Regions made by the Territorialists’ Society for the safeguard of local autonomy and of the role of the small Italian municipalities. Another positive signal is represented by the law proposal, presented to the Chamber of the Deputies by almost 80 Deputies (whose first signatory is Ermete Realacci) for a support and evaluation policy addressed to the municipalities with 5000 inhabitants or less, and for the mountain and rural areas.

Nevertheless, the bill, as for a similar proposal submitted in 2014 by the deputy Patrizia Terzoni, is still under the comment of the Parliamentary Committees of the Environment, Territory and Public Works and of the Budget Committee of the Chamber of Deputies.

“Italy”, declared Realacci, “in order to be more cohesive and competitive should invest on small municipalities, on the strength of the territories and on its widespread beauties”. It is the same spirit of “Voler Bene all’Italia” (Loving Italy), the manifestation realized by Legambiente that consists in almost 200 events and itineraries all over Italy and whose intent is to increase the knowledge about places, little communities and small villages that should be developed. A manifestation that aims at narrating a changing Italy, which want to create new development with a focus on its widespread landscape heritage, which is its main richness. Not everybody is of this same opinion, not even in the Parties in which Realacci and Terzoni are.

In the meantime, among appeals and bills, we should avoid in causing irreversible damages, and we should stop, even in a precautionary way, the attack towards small municipalities, the local political representation and the territorial democracy.

Unfortunately, behind the demagogic discourse of the cuts in public spendings or the rhetoric of the savings, we can glimpse the attempt made in order to hide the fact that real difficulties are into Politics, and not in small municipalities, which are marginalized in the globalization process.

Are they experiencing difficulties?

Well, let’s help them live, not disappear. Furthermore, we have to take into account that small municipalities are often bigger then we believe them: they are small in a territorial dimension but not so small in terms of territorial extension. They are often dislocated in rural or in mountain areas, and thus they often arises specific needs in terms of environmental safeguard.

There should be not the Mayors to declare them dead, after centuries of administrative autonomy, scrupulously watched, even in difficulties and crises.

In a historical phase such the one we’re living, characterized by the increasingly estrangement of public choices from the inhabitants, and characterized by the preponderance of economic-financial powers on the democratic governance, Comuni, intended as real communities of inhabitants and their environmental heritages, should be considered as the base-structure of the Nation, the living heart of Democracy. Particularly, small municipalities should be protected and considered as the strategic field for the future of new socio-economical equilibria of the whole Nation. Agreements, Union of Municipalities, Consortia, Framework Agreements are all effective tools in adopting cooperative management of the municipal functions that don’t cause the loss of autonomy and political representation.

Let’s use these tools, and put to the side anachronistic fusion among municipalities. The Fusion Tool should be used only in the case of micro-municipalities in which the sense of community is already lost. Above all, should be the municipalities themselves in choosing to adopt this legal tool, avoiding the attempts that Regions or Governments could make in this sense within a neo-centralist policies.

“Together and Autonomous” this should be the pay-off in adopting shared policies and providing citizens with associated functions. Should be further avoided the disappearance of municipal administrative centers while safeguarding cultural heritages, and social, democratic and economic values that they own.

In order to create a local development, rural areas need services, culture, care and institutional proximity. It is today the time to look at the small communities and their municipalities. Instead we are living a moving back of the municipal autonomy and a reduction of the powers of local administrations. These are all symptoms of a neo-centralist politics and of an empowerment of governmental control that outline an emerging post-democracy, which features are not so reassuring.

Beyond institutional frameworks, what the territories need is an effective policy centered on the municipalities. We should invest on the centrality of territories and in re-launching the “local” (without being “localists”) to fight against global crisis and politics decay.

In the area of general opposition strategies to the globalization or glocalization processes, returning to the territory could represent a key success factors, prefiguring the “local project” as intended by Alberto Magnaghi in its works of place awareness. This local project is not a sad localism, but it is a renewed attention towards the local communities in the transition from a sustainable development to an auto-sustainable development.

It is for this reason that it is necessary an empowerment of the municipalities, and not their disappearance. What we need is the safeguard of rights and services achieved with difficulties over time, the maintenance of a political representation near the citizenship and the territories, a renewed respect of the local identities and the relaunch of the public participation and of the role of the Town Councils.

Within this framework, it is necessary also to promote a smart process of association among municipalities and to improve an inter-municipal coordination, avoiding a further estrangement of the local government. We should avoid in repeating what already happened for many public services (from water services to the environmental safeguard), because a wider extension of the areas to manage and the distance between the territory and the decision making processes have created negative effects, municipal expropriation, commodification of natural resources and the rise of costs for the citizens.

Inner areas could represent a pilot-project in individuating new economic models and new development paths, focusing on the quality of life and the beauty of the Italian landscape. These resources are not a poet mannerism or an intellectual theme. They are veritable resources for the economic development and the cornerstone for a Country’s civilization.

References

M. Rossi Doria, Dieci anni di politica agraria, Bari, Laterza, 1958.

P. Bevilacqua, Il grande saccheggio. L’età del capitalismo distruttivo, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 2011; Id., Miseria dello sviluppo, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 2008.

Il territorio bene comune, a cura di A. Magnaghi, Firenze, Firenze University Press, 2012.

C. Tosco, I beni culturali. Storia, tutela e valorizzazione, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2014, pp.75-82.

S. Settis, Paesaggio, Costituzione, cemento. La battaglia per l’ambiente contro il degrado civile, Torino, Einaudi, 2010.

A. Tarpino, Spaesati. Luoghi dell’Italia in abbandono tra memoria e futuro, Torino, Einaudi, 2012

F. Arminio, Geografia commossa dell’Italia interna, Milano, Bruno Mondadori, 2013.

G. Dematteis, Montanari per scelta. Indizi di rinascita nella montagna piemontese, Milano, Franco Angeli, 2011.

C. Cattaneo, Scritti politici, a cura di M. Boneschi, Firenze Le Monnier, 1965, vol. IV, p. 425.

Ivi, p. 424. Si tratta di suggestioni riprese in una prospettiva attuale da P. Ginsborg, Salviamo l’Italia, Torino, Einaudi, 2010, pp. 48-54.

R. Pazzagli, Il Buonpaese. Territorio e gusto nell’Italia in declino, Pisa, Felici, 2014, pp. 97-108.

L. Vandelli, Sindaci e miti. Sisifo, Tantalo e Damocle nell’amministrazione locale, Bologna, Il Mulino, 1997.

A. Bassolino, La repubblica delle città, Roma, Donzelli, 1996, p. 92.

V. De Luca, Un’altra Italia tra vecchie burocrazie e nuove città, Roma-Bari, Laterza, 1999, p. 131.

G. Sateriale, Mente locale. La battaglia di un sindaco per i suoi cittadini contro lobby e partiti, Milano, Bompiani, 2011.

Osservatorio delle pratiche territorialiste: http://www.societadeiterritorialisti.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=319&Itemid=166

“Metodi e obiettivi per un uso efficace dei fondi comunitari 2014-2020”, Roma 2012, www.dps.tesoro.it/aree_interne/…/Metodi_ed_obiettivi_27_dic_2012.pdf

http://www.camera.it/leg17/141

http://www.piccolagrandeitalia.it/

C. Crouch, Postdemocrazia, Laterza, Roma-Bari, 2003.

A. Magnaghi, Il progetto locale. Verso la coscienza di luogo, Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 2010.