Introduction

By all appearances, children are now a main target for many cultural institutions. There is no museum that does not devote space and activities for children and, more recently, also concert halls, orchestras and opera houses have opened their doors to the young public and to families(1).

Dedicated cultural institutions for children are also springing at international level: this is the case of Children’s Museums which show a flourishing of new spaces, a more and more structured sector’s organization and a growing public.

Museums part of the Association of Children’s Museum, most of which are based in the United States, collect each year more than 30 million visitors, and also in Europe, the interest in these spaces for children’s “edutainment” has been fast growing since the establishment, in 1994, of “Hands On! Europe”, today “Hands On! International”, first network dedicated to the promotion of the concept of “children’s museum” in Europe.

Also children’s cultural heritage – from the intangible one of games and tales to the tangible one made of places and spaces (Dudek, 2005) – and of its representation which, until recently, has been virtually absent from all the arguments related to museum studies as well as to cultural policies and management, is finding new interest from both the public and the scientific community (Darian-Smith and Pascoe, 2013) (2).

These cultural attractions are mainly addressed to the community of residents but, increasingly, also to young tourist and to their families: the entry of children among the new tourists is a phenomenon visible at the international level and the web, which is a fundamental indicator of social trends, returns clearly this evidence with a multiplication of sites and blogs dedicated to tourism with children.

To be able, at least in vacation, to have some time off from the close supervision/care/help of their children, causes more and more parents to find places that offer specific activities cut out on them. These are not necessarily purely recreational activities such as the now ubiquitous “baby clubs” or “parking” or ad hoc destinations such as amusement parks (which also experienced a boom in recent years as the top 20 European parks have hosted in 2011 than 58 million visitors, TEA/AECOM, 2011), but also specific cultural activities. The market is therefore increasingly focusing on this target, developing new products and services (Friel, 2014).

The portals of many tourist destinations – from Genoa to Amsterdam, Copenhagen or Naples, just to name a few- have now sections dedicated to children, and Rome even has a website in five languages dedicated to small cultural tourists.

Indeed, this blossoming of cultural entertainment for children is a phenomenon linked to the recognition of the importance of education to the arts and of the design of creative activities for children but it is certainly also the result of the development and consolidation of specific marketing practices by cultural practitioners and destinations.

Faced with a situation which has effectively already been structured, though with different goals, it therefore becomes urgent to ask ourselves what role the cultural policies on this theme can play and in what way and with what strategies it is possible to innervate the specific objectives of the cultural policies such as access, inclusion and so on, with those of the individual cultural institutions.

The paper intends to explore how cultural policies are dealing with young citizens and attempts to trace an overview of cultural policies and tools in Europe targeting children.

International models of intervention: a comparative analysis of the European context

The acknowledgement that early exposure to art and culture has a significant effect on the formation of taste, on future consumption and appreciation of culture as well as, in general, on citizenship and social quality, has led many countries to place children at the centre of their cultural strategies and social programs, particularly with regard to inclusion and access.

Yet few have been able to combine children’s cultural consumption policies with policies for supporting the cultural and creative sectors or for drawing up innovative tools of intervention. However, some countries have developed articulated cultural policies on childhood.

The Danish case is particularly interesting due to the wide range of actions undertaken to promote children’s culture and cultural participation. At an institutional level, the Danish Ministry of Culture has a Media Council dedicated to children and the young, while local authorities also have a specific Committee devoted to children’s culture. Moreover, the Ministry of Education oversees cultural education in schools and provides subsidies for various activities devoted to leisure and cultural minority groups. Cultural activities for children are developed by the Network for Children’s Culture established in cooperation with the Ministry of Family and Consumer Affairs and one of the strategic objectives of the Danish Arts Council’s “Action Plan 2007-2011” is to bring children to the arts. Danish cultural institutions spend between 45 and 53 million euro annually on making culture accessible to children.

Sweden has also recently (2009) included the active participation of children in cultural life as one of the objectives of its national cultural policy and enshrined the right of children to exercise their creativity, while in England great political attention has been devoted to the results of the report, “Encourage Children Today to Build Audiences for Tomorrow”, published by the Arts Council of England (Oskala, A., Keaney E., Chan T.W., Bunting C. 2009). This report revealed how cultural encouragement in early age is significantly associated with the probability of obtaining active consumers of art and culture in adult life.

Other countries are strongly involved in promoting children’s culture and culture for children, focusing not only on traditional forms of cultural expression and activities but also on new tools and practices with particular attention to ICT. This attention to the new interests of the younger generations and to the technological tools they use is also leading to the study of new means of fruition and of cultural education aimed at children. The first experiments date back quite a few years as is the case with the award-winning children’s portal of the Polish Ministry of Culture(3) while there are many interesting experiences in course today in museums, theatres, and concert and exhibition halls which, in response to the need to find new audiences (and thereby legitimize public funding), are now using arts education as part of their new marketing strategies with original formats and interactive tools.

In other European countries, the focus of public cultural policies towards the young is not yet fully developed despite the fact that many important public and private institutions are active in the visual arts and performing arts with specific programs for children.

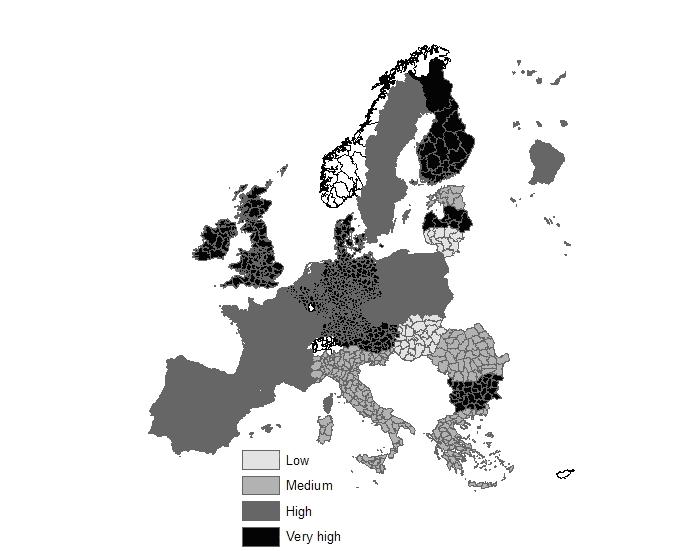

In general, the main areas of intervention of children-related cultural policies in EU countries deal with cultural participation measures, art and cultural education in school and out of school, integration and inclusion policies. Figure 1 offers an overview of the commitment of EU countries based on the presence of these intervention strands among their policy priorities.

Figure 1. The commitment of EU countries towards children-related cultural policies

This comparative examination should be considered as exploratory. It is based on the analysis of institutional sources – i.e. ministries/national bodies dealing with culture – on academic literature and on the Council of Europe/ERICarts monitoring tool, “Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe”(4) and it is not intended to be exhaustive as to describe the status quo of cultural policies in Europe presents a number of critical issues.

Actually, it is only recently that the growing awareness of the importance of culture as a driving shaft for socio-economic development in Europe, has been met with a desire to “reorder” the information regarding this sector. The great differences of a political, legislative, administrative and fiscal type – just to mention a few – between the various Member States, make it difficult to achieve a homogeneous reading of the actions on behalf of culture and the identification of funding directed to it. As regards the procedures for supporting the participation of children in cultural life, in this case too, the tools vary considerably from country to country and, within the individual countries, from one administrative level to another.

These intervention tools involve subsidies and transfers, activities in support of education and training in the arts, and indirect expenditure through tax incentives and exemptions: this is the case, for example, of Malta where, starting from 2012, parents whose children attend courses in cultural and creative teaching institutions will benefit from a 100 euro reduction on taxable income for costs related to courses given by licensed or accredited schools.

A further difficulty in making international comparisons derives from a lack of statistics on children’s cultural involvement: data on their consumption – not only cultural – and on their activities are virtually nonexistent both at a European and at a country level, also because of the statistical noise that may arise in carrying out surveys on this population.

Concluding remarks

Despite the limits of this analysis, in general, it can be stated that, in many countries, the awareness that children should be involved in cultural activities is gaining ground. But the intensity of this awareness, the breadth of the concept of culture adopted and the resources spent on this front vary widely from country to country.

The intervention itself also varies considerably depending on the age of the population considered which, taking into account individuals from 0 to 14 years, covers about 72 million European citizens(5). Most of the measures undertaken concern school-age children while programs intended for children under six years old are infrequent.

But the issue of children in cultural policy emerges as a very important one and is all the more interesting when we consider the evolution of cultural policies and strategies in recent decades, the progress made by studies into the role of creativity and innovation in economic and social development and, finally, the changing nature of cultural consumption.

Accordingly, in a nutshell, cultural policy makers could have at least three good reasons for focusing greater attention on young audiences.

1. From the viewpoint of “culture as development” the subject of cultural policies for children is a central and delicate one, both because “children’s culture is always highly inflected with societal purpose” (Kline, 1998) and because of the auxiliary and mediating role that children can play in cultural policies.

2. It is now widely acknowledged that the birth of new creative talents is a discontinuous stochastic process over time, but the occasion or the social environment can generate extraordinary conditions that provide a necessary critical mass of creativity and produce concentrations of talents located in space and time (Santagata, 2007). It is therefore here that the second point of reflection on the importance of policies for supporting the cultural participation of youngest is inserted: in a perspective of future consumption and support for demand but also with a view to regeneration and adjusting the supply. If it is true that “the long-term foundation of the cultural industries is built upon the talents and skills of artists and other creative workers”(6) it should be added that the long-term foundation of the cultural industries is also built on the cultural and creative cultivation of new generations, and upon new cohorts of consumers seduced by the pleasures of culture.

3. A final consideration regards not so much the formulation of cultural policies as attention focused by policy-makers in monitoring the cultural demand and consumption by children so as to be able to draw up new policies for the future. Estimating participation, characterizing the public, and assessing the impact of the cultural actions undertaken are fundamental for developing cultural policy in a panorama of change in the consumption of culture. The new generations use mobile telephony, the internet and digital media in ways that expand their range of cultural experience and transform them into co-creators of cultural content.

And “the sense of empowerment brought about by these developments […] are likely to continue as significant influences on the content of cultural policy in the future”(7).

Notes

(1) This is the case for example of the Teatro alla Scala in Milan http://www.lascalaunder30.org/la-scala-in-famiglia/la_scala_in_famiglia_2013.html or of the Los Angeles Opera, http://www.laopera.org/Community/Families/

(2) An interesting example comes from the activities and exhibitions of the V&A Museum of Childhood.

(3) www.kula.gov.pl.

(4) www.culturalpolicies.net.

(5) Source: Eurostat, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu.

(6) Throsby, The economics of cultural policy, 2010, p.102.

(7) Ibi, p.5.

References

Darian-Smith K. and Pascoe,C. (2013), Children, Childhood and Cultural Heritage, London, Routledge

Dudek, M. (2005), Children’s Spaces, Oxford, Elesevier

Friel M. (2014), “Turismo culturale per tutte le stagioni: un confronto tra generazioni” in Marra, E. e Ruspini, E. Diritto al turismo: genere e corsi di vita, Unicopli

Kline, S. (1998), “The making of Children’s Culture” in Jenkins, H. (ed.) The children’s culture reader, New York and London: New York University Press

Oskala, A., Keaney E., Chan T.W., Bunting C. (2009) “Encourage children today to build audiences for tomorrow” document prepared for Arts Council England http://www.artscouncil.org.uk/publication_archive/encourage-children-today-to-build-audiences-for-tomorrow/

Sacco, P.L. and Segre G. (2009) “Creativity, Cultural Investment and Local Development: a New Theoretical for Endogenous Growth” in Fratesi, U. and Senn, L. (eds.) Growth and Innovation of Competitive Regions. The Role of Internal and External Connections, Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer

Santagata, W. (2007), La fabbrica della cultura, Bologna, Il Mulino.

TEA/AECOM (2011), Theme Index: The Global Attractions Attendance Report available at http://www.aecom.com/deployedfiles/Internet/Capabilities/Economics/_documents/Theme%20Index%202011.pdf

Throsby, D. (2011), The economics of cultural policy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press