Abstract

The content of this article is the analysis of Web communication strategies used by corporate museums. The main goal of the research is to analyze the Italian corporate museum’s communication in order to first review the digital identity and the reach and engage operations used by them. Through several indicators, the study highlights both strengths and weaknesses of the online strategies used by those samples, which have been selected among Museimpresa partner museums operating in the commodities sector of design.

Introduction [0]

The main essence of museum institutions regards the responsibility, not only to preserve both tangible and intangible testimonies but also to communicate and spread them for the public use. Therefore, it’s necessary to promote and involve in order not to let corporate museums be still an old-fashioned container placed there for mere preservation, a vision that has confused the common belief until last century, paralyzing its communication potentialities.

Corporate museums are the conscious expression of the organized memory which can, and above all have to be used to let the identity communication and the company image evolve (Iannone, 2016). Even though corporate museums are often perceived as secondary ones compared to the historical-artistic or any other kind of museums, actually they have contributed to extend and change the concept itself of cultural heritage (Liggeri, 2015), thanks to the tight bond with its own archive [1] and with scientific contents.

Today, the communication system of museums and, generally speaking, of any places of culture [2], can be displayed following two vectors. The first one is internal and convergent and brings the so-called onsite communication (Cataldo, Paraventi, 2007). It can be explained as a specific language – metalanguage, created by using various ways of communication, from the traditional supports to the new technologies (Vitale, 2010), with the aim to simplify the visitor’s decoding of the exhibits (Cataldo, Paraventi, 2007) and to connect them to the ghosts that linger all around the exhibition.

A choice of tools needed to evoke the resonance and the recognition, in order to track the visitor’s interest, as well as the realization of his own “visual banquet” (Karp, 1995). The second vector, instead, is external – it goes off-site, and requires the use of media and outreach activities, which have to be accessible to the public both before and after the visit. Thus, this is a vector that can work in both cases if the user is inspired by a primary interest that pushes him to consult the social media connected to cultural activities (Cataldo, Paraventi, 2007). Museums, indeed, correspond to the image that they project externally, for this reason, visual design is an essential discipline that has to be involved when planning the communication system, in order to simplify the visitor’s perception with a shared and recognizable language (Vitale, 2010).

Hereby, the connective tissue gets interlaced between the institution needs and the visitor’s ones. This leads to expanding the relationship based on the dialogue of the communication field, a process which is no doubt still in evolution (Ferrara, 2009) and which needs to be enhanced through available web channels, although this is something not completely developed yet. In fact, even though ICOM Italy has recently started a monitoring activity for the museum’s web strategy [3], it still has to be defined in depth. The ICOM Italy guidelines are based on considerations about tools and supports of internal (onsite) communication based on the idea of a thin museum (“museums are not books” [4] ), whereas the issue regarding the use of digital communication for museums institutions is not addressed at all.

The lack of information regarding this topic highlights the need to think about the use of digital communication for corporate museums and to constantly monitor the offer status within general reference lines in order to encourage the visitors’ involvement in an innovative way to build an interactive relationship with them.

Moving further, this research aims to analyze online communication strategies adopted by corporate museums within the design world and those ones partnering with Museimpresa, for the purpose to highlight their strengths and weaknesses. For often being sectorial commodity-related, corporate museums have some difficulties to attract general public who is not interested in the topic, if there is no implement and no planning of the necessary reach and engage operations.

Therefore, it’s essential to wonder how much the new media strategies have been built around the existing museum institution. How do we plan a digital communication for corporate museums today? How much does an online identity characterization affect the visitors’ involvement? How do we outline the emotional approach during narration and interactivity on the website? Starting from those questions, the main goal of this study is to analyze online communication strategies, through a set of main indicators, for a first inspection of the digital identity in corporate museums within the design world.

Corporate Museums and the new communication strategies

The value of democratic inclusiveness of museum institutions is surely alike to the idea of Welfare Europe during the 50s-60s (Milano, Sciacchitano, 2015). In Italy, already during the Seventies (despite being a little late with refers to England and Holland), visual communication in cultural places starts to take shape in order to expand the museums target: in fact during those years the graphics for this kind of communication are defined “public utility graphics” (Ferrara, 2009). From this moment on, the world of museums and, more in general, of culture, starts to wonder about the visitor’s needs [5] , improving the former concept of visitor-student into the visitor-user one who is free to choose.

With this background, it’s important to pursue the aim to get rid of the sense of incompetence and disorientation, supporting a cultural communication based on the public heterogeneity. Museums have to stimulate the visitor, always proposing new ways to look at things: the visit doesn’t have to be something static, but an appointment between the visitor and the museum itself that gets renewed each time (Mottola Molfino, 1991). A place where synesthesia becomes the needed interpretation to involve every sense of the visitor who will be able to acknowledge the message, as Munari defines it (2010), once the insight is stimulated: that is to say the apperception the information get reunited with in order to define a new system of meanings (Cataldo, Paraventi, 2007).

There is no doubt that the level of the visit immersivity is a highly attractive value which the museum can use towards all the visitors not reached yet. Immerisivity is a variable supported by communication which is not only a written source anymore, but also acoustic, tactile, olfactory, interactive with the intention to stimulate all the different kinds of public, or the “learning styles” as Gardner (1989) would define them.

It’s necessary to think about the fact that the public it’s not a uniform mass, but rather a heterogeneous entity, crucial for the museum life through every choice it makes. For this reason, the audience development, or the set of actions to expand and diversify the public, doesn’t have to be understood by cultural institutions as a mere quantitative increase of public, but as active participants to the museum suggestions, managing to increase the quality of the experience (Bollo, 2014).

There is an implicit division between who decides to get in contact with the institutionalized cultural world and who, on the contrary, wants to stay out of it for so many reasons that it’s difficult to track down the causes. Through the personal choice to establish a pact with the museum institution, the reachable public and non-reachable public, or non-public, it’s determined.

The 50 shades of public theorized by Bollo (Bollo, 2014) include both the easily involved users and the occasional ones, passing through the potential ones too, until mentioning the non-public, accepting the fact that the latter one, not interested, can’t be reached by the communication strategies of the museum institution. In particular, there are two phases, strictly related, where Bollo (2014) divides the ways to build and preserve a dialogic relationship with the users willing to interact: the first reach phase and the following engage one. The term reach defines that communicative phase in preparation to the potential public interception. An initial phase, in line with the essence of the contemporary museum which has to try to always be attractive, accessible and updated when creating meanings to narrate to the variety of existing kinds of public (Cataldo, Paraventi, 2007). This first phase is composed of the union of communicative-promotional operations and strategies, mainly off-site, which the museum decides to start also investing in unusual, approached, going beyond its own world. Thus, the role of digital communication in this first approach is surely extremely important in order to reach the aim of intriguing the potential visitor.

The second phase tracked by Bollo (2014), following the first one, is the engage phase, that is to say the involvement one: once having won the threshold effect (Lugli, 1992; Cataldo, Paraventi, 20079, after having won the social, cognitive and psychological barriers to approach the museum reality, it’s up the engage activity to satisfy, intrigue, but also loyalize the visitor. It’s really important that the visitors are put in the condition to be participatory co-curators (Simon, 2010), who can enjoy themselves, interact, participate, create in order to improve their knowledge and the self-realization for the experience they had.

The Simon’s participatory museum (2010) [6] is now overflown the banks of the physical architecture and the local communicative set, passing to the will of the users themselves to create multimedia contents through the available channels, evolving, as of from web 1.0 to web 2.0, from Museum 1.0 to Museum 2.0 (Bonacini, 2012), where the visitor-user has now an interactive role (Bollo et alt, 2014).

Actually, this is a role already played by the users, as the nature itself of social media allows to work on customized self-expression criteria, where the concept of individual identity gets expressed when declaring the appreciation, the satisfaction and above all the choice of a selected connection with other profiles, pages, and groups. One example is represented by social media like Facebook which need a detailed digital representation of their account to improve the interaction with other users; or semi-professional channels like LinkedIn that are conceived to create a network of acquaintances starting from selected connections (Simon, 2010). As Simon defines it, this is a “from me to we” process which, if used in cultural contexts, could give birth to a community of users having the same artistic interests, like museums, that could become part of daily debates (Bonacini, 2010).

Furthermore, another aspect of promoting concerns the experimentation of advertising communication in some historical-artistic museums, tracing in those conversation techniques an appeal fascinating for the contemporary user. For this reason, often tempting languages inherited by the advertising glossary, are freely supported by cultural themes, as if it’s not a commercial product that has to be sold, but rather an experiential and immersive opportunity of cultural growth (Ferrara, 2009).

Great examples of communication come indeed from museums which, internalizing the contemporaneity of socio-cultural changes, are committed to involving visitors with a jargon similar to that one of social media. A great example could be the website structure of Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, where there is the possibility to create a personal account and to select the artworks in order to create a customised board thanks to an appreciation system similar to the “like” one.

It’s a way of approaching that is alike to one of the main and most used social networks among young people, Pinterest, which relies on the picture rather than on a written text for its own communication [7]. An engage like this opens new frontiers and tips for corporate museums communication which, even though in different ways, as a start should have the idea of immersive and participated co-author (Bollo, 2014). Corporate museums, indeed, can be thought as narration tools for the heritage-based company that wants to keep and enhance its own heritage, its own story, (Iannone, 2016) adding value to the corporate cultural patrimony (Montella, 2010).

When a company decides to promote itself through a museum, inevitably looks for connections with its own identity values which distinguish it from the others with the same commodity-related sector, becoming the plus factor to stand out among other competitors. A necessary asset (Iannone, 2016) on which Italian companies that have built their own corporate identity with values like craftsmanship and quality of processed raw materials, manage to compete with the worldwide production system. For this reason, a meticulous historical connection it’s not less important than other factors, being a value that acts in a retroactive way through a representation of the maintained and/or increased quality from the start up to now, influencing than the image perception and the corporate reputation (Martino, 2013). Even though the world concerning Museimpresa can give hope for an always growing promotion and involvement of museums in social network activities, currently some partners keep themselves quite distant from the idea of structured and strategic corporate communication. This is not a minimal factor, especially when using the new participatory platforms like social networks that, even if they are channels suitable for an effective identity and patrimony promotion, able to reach groups of a younger audience (Martino, 2015), for management reasons are rarely used in offsite communication strategies.

With the aim to increase industrial tourism and to attract new visitors, planning an adequate digital communication is more than necessary for corporate museums that understand the importance to develop relationships and collaborations with the cultural, receptive, enogastronomic, artisanal and artistic world on the spot. In this way, museums could be able to promote themselves through the web and social channels, enhancing the network created from the cooperation with the new regional excellences (Liggeri, 2015). An active exchange which is only possible through the new technological frontiers that can act as cultural mediators also with that public target more difficult to reach, like for example those so-called Millennials [8].

Objectives and methodology of research

The objective of this research is to analyze the online communication strategies adopted by corporate museums within the design world, in order to obtain a complete view of the status of the social network and website communication as an art. In particular, the study got its inspiration from Vitale’s classification (2010), according to which museum communication has to trace six fundamental adjectives: it has to be true, reliable and verified, based on demonstrable data; it has to be social and useful to the community; it has to be reasonable, belonging to an overall vision of meanings based on identity; it has to be holistic, never fragmented and included in a harmonic context; it has to be differential, which means innovative when creating an image against the trend; it has to be widespread, that is to say, it has to concern every aspect of interaction, like for example the museum education. All those criteria and observations can be used for the several existing museums, whether they are art museums, archeological, historical or natural history ones, or technology, ethnographic, experiential or corporate museums which, for being strictly related to the advertising and marketing communication sphere, they shouldn’t have any trouble finding strategies of adequate promotions.

With refers to this research, the study has been focused on the study of seven corporate museums within the design sector which are partnered with Museimpresa (Alessi, Bitossi, Cimbali, Kartell, Molteni, Poltrona Frau, Rancilio). The study has planed the creation and appreciation of a specific master analysis, from one side to verify the digital communication strategies used to enhance the corporate identity and the corporate museum, from the other side to analyze the social network tools when enhancing the involvement and the interactive participation of the different users.

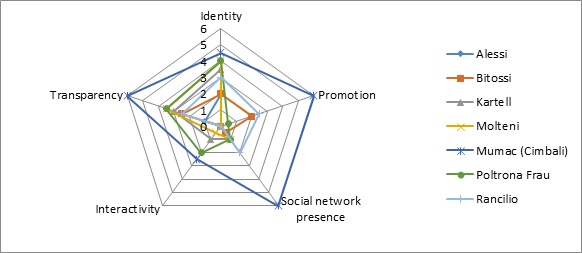

There are five main indicators the research has focused on: identity, promotion, social network communication, interactivity, transparency. Identity, which means the core identity that museums represent in virtual spaces and that develop a coordinated image of, concerns the following sub-indicators: existence of a dedicated museum website, the presence of strong identity elements like mission, vision, museum logo, elaboration of an itinerary storytelling, definition of a virtual gallery for a 360° vision of initiatives linked to the museum and to its collections. Promotion means a mix of offsite strategies for the implement of audience development, but also the corporate image and the corporate reputation.

The promotional aspect has been analyzed through sub-indicators concerning the creation of updated contents, like: the presence of a calendar with current events, museum news like awards, nominations, press release, but also a proposal of scheduled activities in the museum and sharing of collaborations with other institutions, artists, research centers within the area.

Social communication regards, on the contrary, the presence of the museum institution in the most used social networks among cultural institutions, taking into account the chance to trace folksonomies not officialized by the institutions. Those social networks can be divided into those ones with more written text presence like Twitter, Facebook, and those ones which prefer the visual narration through images or audiovisual support like Instagram, Pinterest, YouTube.

Interactivity, or the dialogic integration between users and institution which is created through the use of new technologies, is analyzed through the following sub-indicators: presence of video support on the web page, the chance to interact thanks to virtual tours, games, video games, quizzes released by the museum, the itinerary customization thanks to the themes explained in the website which can be downloaded for free or bought online.

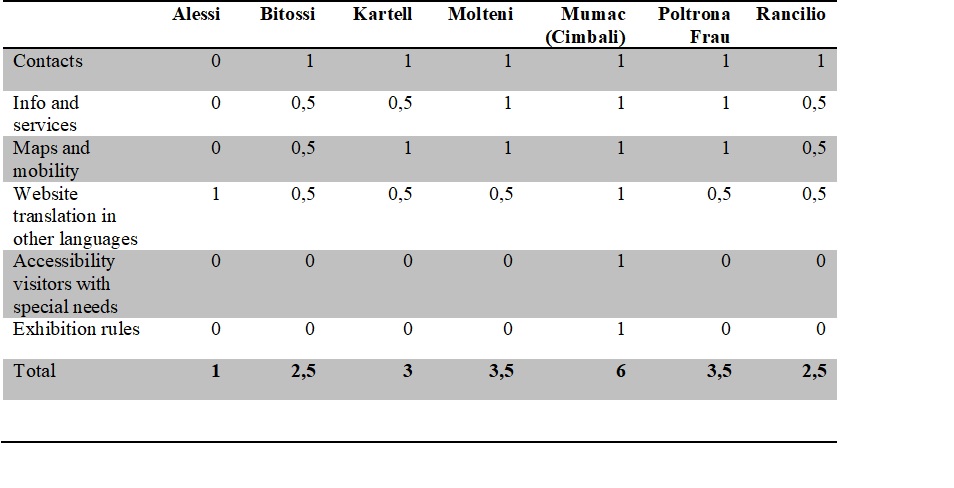

Lastly, with the term transparency, it has to be intended the right accessibility to the information needed to start the visit. The selected sub-indicators concern: facilitation when looking for general contacts like the address, the presence of information about all the available services, recommendations about directions to the museum, the website translated into other languages starting from English, physical accessibility for group of users with special needs and sharing of online visit rules able to anticipate the visitor’s requests.

The persistence of all the items according to a value ladder from 0 to 6 for each item [9], has allowed defining the different level of efficacy of digital communication strategies promoted by corporate museums. Specifically, the obtained scores have been placed within a range going from a basic level of digital platform elaboration to facilitate both information and promotion, up to a more sophisticated level of planning for the user’s emotional involvement and participatory interaction.

Online communication: the main results

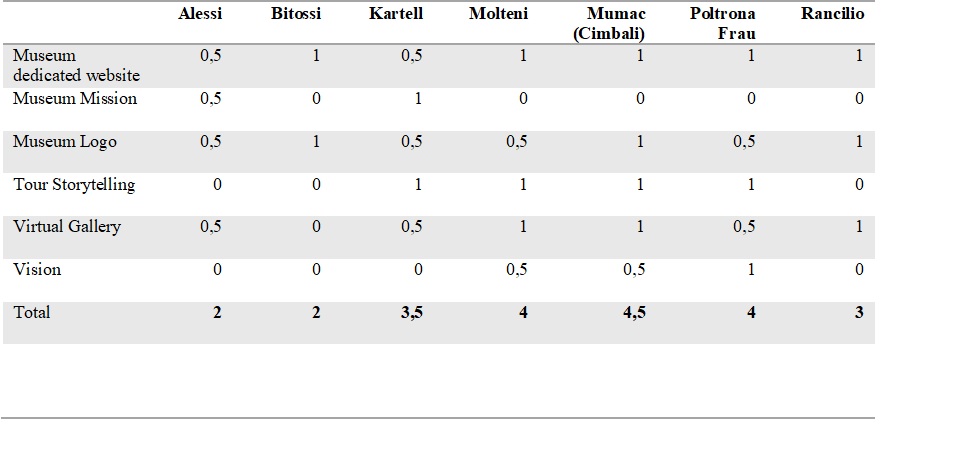

The “identity” indicator (cf. Chart 1) is mainly used to verify whether the web-based Communication is strategically built on the existing museum institution. The term identity means the perception awareness that the museum has of itself, that is to say, its self-recognition of existing in relation to a territorial, social, historical and cultural context. The identity characterization is particularly strong when considering Mumac museum, the corporate museum of the Cimbali Group, which reaches a presence of 4,5 out of 6 sub-indicators, followed by Poltrona Frau and Molteni museums which obtain a score above the standards with 4 out of 6 sub-indicators covered. Kartel and Rancilio have respectively 3,5 and 4 out of 6 sub-indicators, and, at the end, there are Alessi and Bitossi which don’t reach the standards, with 2 out of 6 sub-indicators.

It has to be highlighted how the majority of museums, 5 out of 7, have a dedicated and independent web page for the museum communication. Kartell and Alessi museums partially fulfill this requirement: they don’t have an independent URL from the corporate institutional website, even though they are the only two examples to satisfy the parameter concerning the declaration of museum mission, one of the fundamental documents [10], together with the company agreement, the charter, the legal status which, according to the ICOM Code of Ethic [11] permanent institution, has to be compiled. It’s particularly interesting the identity characterization of the Kartell museum website where there is a chapter dedicated to the museum narration and it’s specifically entitled “The Mission”.

Furthermore, when defining the core image, the museum has to tell its own identity through a coordinated visual device, starting from the planning of an identifying logo. The indicator representing the logotype presence is fully covered by Mumac museum, but also by Bitossi and Rancilio museums, which for this parameter obtain the highest score. On the contrary, the remaining museums, Alessi, Kartell, Molteni, Poltrona Frau, only partially cover the presence as they don’t have a logotype created ad hoc for the museum institution: they just have a declination of the main brand one, with little variations sometimes when selecting the color or simply adding the term “museum” to the corporate logo.

The company, when deciding to invest in a museum realization, apart from assets, it has to invest in energies to search for its own identity, property and history figure (Amari, 2001) which has to be correctly communicated both through a coherent visual device project and through narration.

The sub-indicators concerning the tour storytelling, the virtual gallery presence, are indeed useful parameters to understand the level of online patrimony and collections sharing. Mumac and Molteni fully cover both items, followed by Kartell and Poltrona Frau at the same level, Rancilio, Alessi and lastly Bitossi which doesn’t cover this item at all.

As far as the vision sharing is concerned, that is to say the expression of one’s objectives narrated with the company representative people like the founder, the curator, the senior manager or the project architects, the first places of the previous sub-indicators get tipped over, as Poltrona Frau is the only one museum which gives the idea of future vision through video messages by the senior management, followed by Molteni and Mumac which partially express the vision, whereas there is a total absence in the other samples. This analysis highlights the need for the corporate museum, a complex and not very analyzed channel compared to its rapidity of expansion (Negri, 2003), to clarify with an entire project its own identity and institution figure, sharing it with the audience in different ways, preventing any danger to be perceived as an exhibition area with a merely aesthetic value.

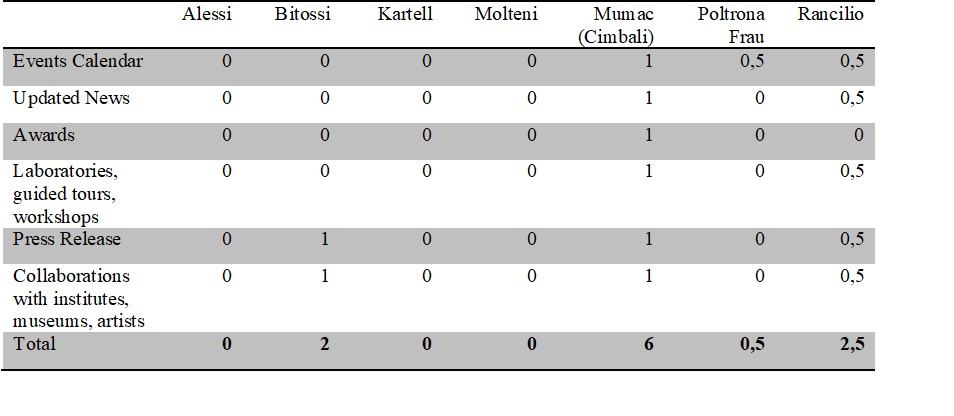

The “promotion” indicator (cf. Chart 2) deals with all the operations needed to increase the audience development and to implement the level of users’ interest reinforcing the corporate values transmission.

When implementing promotional strategies, the gap among tested museums becomes wider touching the extremities of the assessment scale. Mumac positively responds to all the items, obtaining a partial score of 6 out of 6 sub-indicators, while the other samples are still below the average, like: Officina Rancilio which reaches 2,5 out of 6 sub-indicators, Bitossi which has 2 out of 6, Poltrona Frau with 1 out of 6, and lastly Alessi, Kartell, and Molteni which promotional operations can’t be observed in any analyzed item.

The parameter for the share of mentions, applications and won awards is the sub-indicator with the least satisfying assessment, as only Mumac has some contents in this area, whereas in all the other sub-indicators the Cimbali museum is constantly flanked by Rancilio sample which partially covers the parameter, using its Facebook page for any kind of promotional communication without any distinction in the type of information. On the contrary, the sub-indicator concerning the presence of an events calendar is that one with the highest response as, apart from Mumac and Rancilio, also the Poltrona Frau website has a space dedicated to the communication of promoted events, even though it appears it hasn’t been updated for a while.

Differently, it seems that the information needed to the service fruition are less complete, as in the respective web pages the users’ questions get redirected to generic email addresses or to a compilation of standard forms. Furthermore, through the analysis of the presence and accurate update of a press release for the museum and through the promotion of collaboration with cultural institutes in the area, research centers, artists, apart from Mumac and partially Rancilio, also Bitossi positively responds with the highest score in both items.

It seems useful to specify how Mumac covers the various promotional areas starting from planning a website which allows the user to select the kind of experience that he wants to have inside the museum, listing the tour and the workshops according to the type of users, like for example schools, universities or families. The cultural potentialities of museums, in particular at a level of reputation and social responsibility, are necessary to adequately install a dialogue with institutions like universities, other kinds of museums, foundations, galleries and many others in the territory, putting together the corporate marketing with the territorial one (Liggeri, 2015), promoting the corporate culture deployed in less touristic production areas.

The activities promoted by Mumac tend to create new cultural synergies, like collaboration with “La Scala” Theatre in Milan, together which brings on stage a play entitled “Si va in scena! Miscela lirica: quando il caffè incontra l’opera” (Trad: “It’s showtime! Lyric mixtures: when coffee meets the opera”). Moreover, the museum itself is involved in outreach activities, out if its architectural borders, with the “Pagine all’aroma di caffè [12]” performance (Trad: “Pages filled with coffee aroma”) performed by Eco Di Fondo theatre company at the Turin Book Fair.

Therefore, all the events and activities proposed by Mumac are promoted through the website and social network channels with constant updates, as the institution understands the importance of collaborations with both cultural and arts sectors which, apart from increasing the reputation of corporate museums, also implement the corporate image and the corporate reputation of the brand.

Those observations don’t want to exclude that the other sample museums work together in those kinds of initiatives. On the contrary, they want to highlight the missed promotional opportunity in not communicate them outside that sectorial area. This could be an operation that could positively influence the interested stakeholders who are really keen on the possibility of an actual on-site tour.

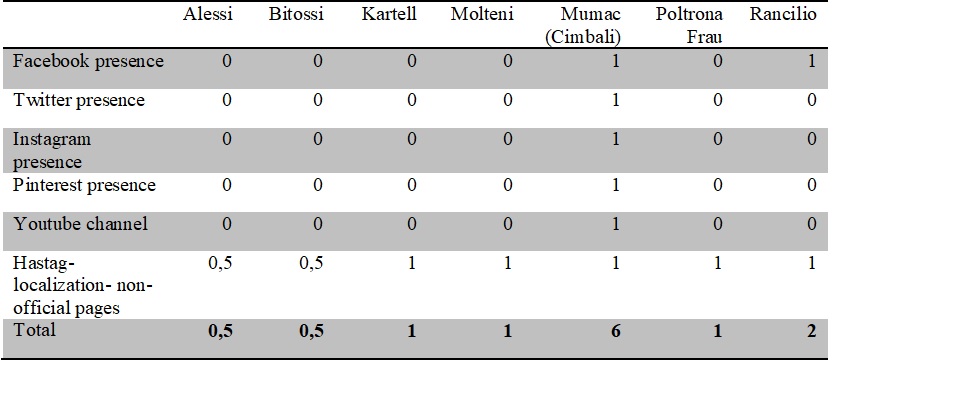

The indicator dedicated to social networks (cf. Chart 3) just wants to trace the presence or absence of museum institution in the main social networks used for cultural communication and analyzed by Fitzcarraldo Foundation (Bollo et al, 2014).From a first observation, it is evident how in this indicator the assessment range goes from the highest score to a total absence. The analysis grid, indeed, shows that Mumac is satisfying for all the identified items, reaching the total highest score. Whereas, except for Officina Rancilio which has an official Facebook page, the there samples do not have social network channels directly linked to the museum. What happens is the museum’s profiles are included in the corporate official ones, as happens for the previously analyzed web pages.

Therefore, 5 samples out of 7 don’t accommodate any item: this absence is filled with elaboration and creation of non-official contents by the visitors themselves who take the role of folksonomies co-authors.

In particular, as the Kartell case, it’s shown the presence of a Facebook page which is not officialized by the institution, where users share their own experiences with pictures, videos, hashtags and localization of the place. The creation of contents by the users is a process that can’t be underestimated, in line with the idea of participation and co-authoring (Bollo, 2014, Simon, 2010). This is a bottom-up process which should influence the planning of the museum communication strategies, up until a decisional level.

It can be wondered why, although social networks are for free, they are not taken into account by corporate museum institutions when planning the communication setup. This often happens for management reasons, of content creation and always updated information which needs the right time and the right knowledge. This absence reinforces another gap which, according to Bonaccini, it’s not just a presence factor, but it’s a “semantic gap” between the museum scientific-institutional language and the current users’ logic-colloquial one (Kalfatovica et al. 2008, Finnis 2008, Hinton, Whitelaw 2010; Bonacini, 2012). This gap should be reduced encouraging the active participation.

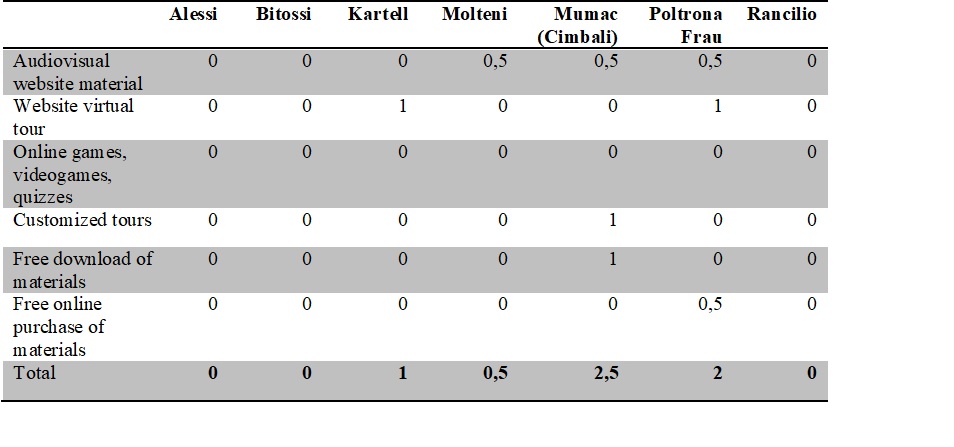

“Interactivity” is the union of all the operations to favor the information exchange between two systems, museum, and visitor; Percept and preceptor (Bottoli, Bretagna, 2013). The interactivity indicator is not satisfying: its assessment range, indeed, decreases, obtaining as highest score the Mumac with 2,5 out of 6, followed by Poltrona Frau with 2 out of 6, Kartell with 1 out of 6, Molteni with 0,5 out of 6 and Alessi, Bitossi, Rancilio with a total absence in all the sub-indicators.

Even though almost none of the item is satisfied, the chance to develop virtual tours in two of the samples, Kartell and Poltrona Frau has to be highlighted, together with a customized tour according to the type of users and the possibility to buy material which can be downloaded for free in Mumac. Other parameters are partially covered, like the possibility to buy the online museum catalog (Poltrona Frau) and the presence of audiovisual material (Molteni, Mumac, and Poltrona Frau). Nevertheless, the videos available on the web pages go from one to a maximum of two and even if they can be considered the material of a great content value, on the other hand, they are always the same from the inauguration day or relevant events.

Comparing the total absence of satisfaction in the interactive sub-indicator concerning the presence of games, video games, and quizzes online with initiatives like an investment for the creation of the “Father and Son” video game by the Archeological Museum in Naples [13], there is an interactive gap between corporate museums and historical-artistic ones. The latter one, indeed, seemed to have understood the importance to invest in new communication strategies, positively differentiating the current visitor’s needs who have to be able to get closer to the cultural institution also thanks to the use of popular, spread and technological involvement operations.

In a setting where a famous museum like the MoMA in New York allows to freely download the catalogues of all the exhibitions from 1929 up to now, it seems almost anachronistic that corporate museums don’t provide the free download of materials like graphics, period advertisement, paintings, stories about the museums or memories from designers and architects who have worked with the brand in the past. Thus, the interactive communication it can be opened a wide gap between corporate museums and historical-artistic ones, where the corporate museum appears as if it’s still anchored on a logic of traditional museum, not in line with the real progress of contemporary museology.

The last indicator concerns “transparency”, or the clarity and accessibility of data according to the user. This denomination gathers all the information concerning the museum which are useful to the user, like: contacts, opening hours, how to get there, tips regarding public transport, guided tour booking, activities inside the museum, organization etc. An initial orientation which, starting from the web page, should express the nature of the institution with the user is getting in contact and its operation also during a not in-depth web surfing. It seems appropriate to highlight how the corporate museum is not an easy-to-decode institution, strictly linked to a corporate culture, complex and not very famous subject, for this reason, the information notice will have to be as much limpid, direct and easy-to-track as possible.

The analyzed indicator seems to be quite satisfying in all the analyzed cases, as it’s also the simplest one to get started. Yet, also in this case, there are important differences among the information given from a sample or from another one. The sub-indicators concerning the presence of contacts, information, and available services, directions and advice on how to get there, are fully satisfied by Molteni, Mumac, Poltrona Frau, followed by Kartell and progressively by Bitossi and Rancilio.

There is still a lack of information in the Alessi website because, for being a museum directly managed by the company and incorporated within the general communication of the brand, it could not be open to the public in standard time slots. On its website, there are general company contacts which refer to a form to fill, another step that could discourage a potential visitor. Nevertheless, Alessi museum widely satisfies the sub-indicator concerning the linguistic accessibility thanks to the translations into English, French, Spanish, German and Japanese. Also, Alessi has its website translated into at least 10 languages, while the rest of samples provides translations of their websites only in English.

Other two sub-indicators concerning accessibility, now related to its physical nature, are those ones about ways to get in for the visitors with special needs and to sharing of visit rules. Those are essential tools which guarantee to plan the tour anticipating the various kinds of audience’s needs. The only one sample which covers both items is Mumac which, on its website, has tour rules where there are information like, for example, the possibility to introduce a camera inside the exhibition. Furthermore, on the same page, there are also the information to an easier access for disabled people and for pregnant women or women with a baby carriage. Those are the types of visitor that have to be safeguarded with special precaution also during their tour.

Overall results

To conclude, according to an overall vision, resumed in diagram 1, there are some interesting considerations to highlight. The identity characterization seems to be the strongest dimension as far as the ability of museums to communicate online and to coordinate themselves in an integrated vision is concerned. It has to be enhanced, on the other hand, how the identity aspect is not very outlined in almost any museum: this confirms the lack of museology research developed from the institution foundation by the matrix brand. Very often companies, thinking about museums just as exhibition places, don’t understand that they are taking part in the creation of real permanent institutions devoted to culture, with the aim to preserve and enhance testimonies, thus helping the historicization of corporate culture (Martino, 2013). It’s very interesting to highlight the almost total absence in the analyzed samples of a mission, of a charter, a set of rules. This is the expression of the lack of involvement of professional experts necessary to the creation of a proper museum, like a museologist, a museographer, design historian, a communication expert, a visual designer, a linguist, a museum education expert, a cultural marketing expert, an art graphic designer.

Sometimes, indeed, the huge waste of initial capital, like the creation of architecture boxes by prestigious brands [14], leads to the depletion of economic resources that should be used to manage the corporate museum (Liggeri, 2015). What has to be said is that the museum, without planning the right communication strategy, will never be able to autonomously attract any audience, not even in situations where the brand has an influential appeal (Amari, 2001).

In short, it’s proved that the biggest weakness for all the sample museums is the indicator related to the interaction dimension. The almost total absence of any score related to this area is indeed a clear reflection of the lack of investment in new communication strategies and technologies which have the aim to increase the audience development not only at a quantitative level, but above all at a qualitative one: this is necessary for the cultural institution to survive.The insufficiency of invested capital in the interactive sector widens the gap with the other types of museum mentioned above which are more innovative in experimenting new off-site interactive strategies and try to reach as many users as possible, especially the more difficult to reach ones like, for example, teenagers for a specific and sectorial museum (Cataldo, Paraventi, 2007).

Conclusions

The analysis shows some interesting considerations. The first one concerns the need of an innovative use of web communication, through a more integrated perspective in line with the corporate policies. The strategic enhancement of technologies should be considered as the creation of a holistic dynamic microcosm in which its main actors, audience development, and marketing strategies, are combined with museums informative and educational goals (Bollo et ali, 2014).

For this purpose, the museum has focused on a series of actions, aimed at offering new online communication strategies, intended to encourage the sense of belonging and to involve the visitor in a real experience. Transposing the reach and engage steps theorized by Bollo (2010), they can be defined as not well developed inside the company which often delegates the existence of the museum reputation to its brand, not considering the cultural institution as an autonomous operative entity. In this regard, it is important to note a gap between the strategies applied by traditional museums and the ones used by corporate museums.

The first ones experiment the use of media aligned to the needs of the contemporary visitor (as in the gamification example by MANN), while the second ones base their own communication on old strategies, aiming to the status of artistic-historical museums. This phenomenon can mainly be observed in design museums where obsolete ideas of communication do not permit the evolution from Museum 0.1 to Museum 2.0 which is open to participation and cooperation through the dialogue and sharing processes (Bonacini, 2012).

A second consideration refers to the emotional approach of the website narration, using methods such as the storytelling. Our analysis highlights a websites narration mostly from an informative point of view rather than from an interactive one. The storytelling emotional approach, instead, should allow to structure a multiple-levels narration and to stratify the cognitive notions according to each visitor’s need and interest who will track them himself during his virtual experience. Thanks to a positive initial imprinting, based on this kind of approach, the visitor will be able to gain more awareness, getting over his critical resistances. Thus, once involved and stimulated, the visitor will catch all the inputs of the collection, of the context and all the related clues (Montella, 2010).

The third reflection is about a wider use of social networks in order to create a more active visitor, almost like a co-author of the museum values. Using social networks enables the museum to decline its presence on the web, using a colloquial language, less formal, but drawing on scientific information in order to try to involve the social network users. If they will be satisfied and intrigued, indeed, they could transform their virtual experience into an actual visit (Cataldo, 2014). As pointed out by the analysis, creating social communities on Facebook or Twitter should be the right method to actively involve the audience in the cultural process through different channels (Bonacini, 2012).In fact, one of the main purposes of the corporate contemporary museum is certainly to achieve an experiential environment both off and online, which could simplify the connection with the brand, its past history and its commodities sector (Iannone, 2016).

This aspect seems to be easier to reach for those corporate museums which look for a natural connection with the visitor thanks to a strong emotional impact, an even more essential aspect for the less evocative brands which should plan a winning communication strategy. As highlighted by the Fondazione Fitzacarraldo studies, also social networks should be used pondering real needs and potential management opportunities for the company. Is therefore of primary importance to choose a suitable communication, because some corporate museums have the same, or maybe more, followers than the most popular art museum in the world. A perfect example could be Ferrari museum in Maranello that on its Facebook page has reached 172,938 likes exceeding the 30,420 likes of Uffizi Gallery [15].

In conclusion, the main goal of a corporate museum is to be at the same time promoter of the company identifying elements and a cultural institute with its own communication strategies to be specifically developed. According to Iannone’s theories (2016), the corporate museum is the expression of the brand heritage communication and it should be harmoniously and coherently declined inside and outside, in order to create a correct sensemaking, which represents what is perceived.

Lastly, in order to ensure the proper correlation between the museum and main brand, it’s strictly necessary that those two worlds communicate with each other. Thus, the company should transmit the identity values to the museum in a propaedeutic way, even before starting to use it as a communicative external channel (Amari, 2001), beginning with the creation of a historical awareness (Martino, 2013). A useful corporate museum may be positively valued when becomes a brand medium, enhancing and transmitting its corporate identity, its corporate image and its company reputation (Montella, 2010). Anyway, in order to satisfy its role of popularizer, the museum needs to plan at best its own online communication strategies, defining its identity, its mission, promoting its work and the objectives to be fulfilled as most traditional museums would do.

Footnotes

[0] Lucia D’Ambrosi took care of introduction and conclusions. Ilaria Gobbi wrote the main corpus.

[1] It should be noted that the difference between archives and museums arises from the authenticity of the preserved testimonies. In fact, while the museum can exhibit unconfirmed testimonies expressing the doubt to the visitor (for example, the date of a work of art indicated with the “?”), on the other hands the archive collects, preserves and catalogs only official testimonies.

[2] The term “places of culture” includes all the institutions that permanently or temporarily carry out activities of great cultural importance in the territory.

[3] The research is carried out by Digital Culture Heritage of ICOM Italy, in collaboration with the General Direction of Museums and is addressed to all institute and places of culture with a website.

[4] Definition took from the intervention of Mottola Molfino during the “La Parola scritta nel Museo” conference, promoted by the Tuscany Region in 2008.

[5] For this reason, Ronchey Law of 1992 indicates an extension of the museum services offer in Italy, focusing the attention on the visitor, extending the museums proposal with the so-called additional services, such as coffee bars, restaurants, bookshops.

[6] The participatory museum is an online book written by Nina Simon, a freelance curator with great experience in participatory design. Thanks to the experience in this field, Simon creates Museum 2.0, a design company that works with museums, libraries and cultural institutions around the world, in order to carry out dynamic exhibitions and educational programs led by the public.

[7] <https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio-award>

[8] Term taken from Strauss and Howe’s studies.

[9] “1” if the indicator is fully present, “0,5” if it is partially present and “0” if it is completely absent, for a partial score of 6/6 points maximum for each indicator and a total of 30/30 points gathering the five main indicators together.

[10] “The board of directors should ensure that each museum has a written and published constitution chart, statute, or other public documents in accordance with national laws, which clearly state the museum’s legal status, mission, permanence and non-profit nature.” (from ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums).

[11] The Code of Ethics was adopted unanimously at the 15^ ICOM General Assembly in Buenos Aires (Argentine) on 4th November 1986. It was modified and renamed as ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums during the 20^ ICOM General Assembly in Barcelona (Spain) on 6th July 2001 and finally revised by the 21^ General Assembly in Seoul (Republic of Korea) on 8th October 2004.

[12] On the MUMAC website, under the “news & events” section, is traced the current and past initiatives promoted by the museum. It should be noted that several operations are proposed for an audience of children, as the “Pastry Laboratory” on 28th May, 2017. In the same section there are also announcements of awards won by the museum, like the special mention in the fourth edition of the CULTURA + IMPRESA Award.

[13] It seems interesting to note that MANN is the first World Archaeological Museum to produce and distribute a free videogame.

[14] Such as the Poltrona Frau Museum, designed by the architect Michele De Lucchi in 2012.

[15] Data taken from the official Facebook pages of the two museums on 27/06/2017.

Bibliography

AMARI M. (2001). I musei delle aziende. La cultura della tecnica tra arte e storia. (2^ed). Milano, Franco Angeli.

BRETAGNA, G., & BOTTOLI, A. (2013). Scienza del COLORE per il DESIGN. Milano: Maggioli Editore

BOLLO, A. (2014). 50 sfumature di pubblico e la sfida dell’audience development. In. DE BIASE, F. (2014). I pubblici della cultura. Audience development, audience engagement. Milano: Franco Angeli.

BOLLO, A., et ali. (2014). Il Museo e la Rete: nuovi modi di comunicare. Linee guida per una comunicazione innovativa per i musei.

BONACINI, E., (2010). I musei e le nuove frontiere dei social networks: da Facebook a Foursquare e Gowalla. Fizz – oltre il marketing culturale.

BONACINI, E., (2012). Il museo partecipativo sul web: forme di partecipazione dell’utente alla produzione culturale e alla creazione di valore culturale. Il Capitale Culturale N. V, pp. 93-125.

CATALDO, L. (2014). Musei e patrimonio in rete. Dai sistemi museali al distretto culturale evoluto. Milano: Hoepli.

CATALDO, L., & PARAVENTI, M. (2007). Il Museo Oggi. Linee guida per una museologia contemporanea. Milano: Editore Ulrico Hoepli.

DA MILANO, C., & SCIACCHITANO, E. (2015) Linee guida per la comunicazione nei musei : segnaletica interna, didascalie e pannelli. Roma.

FERRARA, C. (2009). La comunicazione dei beni culturali. Il progetto dell’identità visiva di musei, siti archeologici, luoghi della cultura.(2^ed.). Milano: Lupetto Editori di Comunicazione.

GARDNER, H. (1989). Formae mentis. Saggi sulla pluralità dell’intelligenza. Milano, Feltrinelli.

IANNONE, D. (2016). Quando il museo comunica l’impresa: identità organizzativa e sensemaking nel museo Salvatore Ferragamo. Il Capitale Culturale, N.s., XIII, 525-553.

ICOM Italia (2009). Codice etico dell’ICOM per i musei (L. Baldin et ali trad.). Milano, Zurigo.

KARP, I., & LAVINE, S.D., (1995). Exhibiting Cultures. The poetics and Politics of Museum Display (M. Gregorio,D. Moretti, A. Serra trad.). Bologna: CLUEB.

LIGGERI, D. (2015). La comunicazione di musei e archivi d’impresa. Bergamo: Lubrina Editore.

MARTINO, V. (2013). Dalle storie alla storia d’impresa. Memoria, comunicazione, heritage. Acireale: Bonanno Editore.

MARTINO, V. (2015). Made in Italy museums. Some reflections on company heritage networking and communication. Tafterjournal, N. 84.

MONTELLA M.M. (2010). Museo d’impresa come strumento di comunicazione. Possibili innovazioni di prodotto, processo, organizzazione. Esperienze d’impresa, n. 2, pp. 147-164.

MOTTOLA MOLFINO, A. In ANDREINI, A. (A cura di). (2008). La parola scritta nel museo. Lingua, accesso, democrazia. Atti del convegno presso il Centro Affari e Convegni di Arezzo, 17 Ottobre 2008. Arezzo.

MUNARI, B. (2010). Da cosa nasce cosa. (23^ed.). Bari: Laterza.

NEGRI, M. (2003). Manuale di museologia per i musei aziendali. Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino.

SIMON, N. (2010). The Participatory Museum.

VITALE, G. (2010). Il museo visibile. Visual design, museo e comunicazione. Milano: Lupetti.

Sitography

<http://www.alessi.com/it/azienda/museo>

<http://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/export/MiBAC/index.html#&panel1-1>

<http://www.fitzcarraldo.it>

<http://www.fondazionevittorianobitossi.it/museo_artistico_industriale_bitossi_>

<http://www.kartell.com/experience/it/museum/>

<http://www.icom-italia.org>

<http://moltenimuseum.com/it/>

<http://mumac.it>

<http://www.museimpresa.com>

<http://www.museoarcheologiconapoli.it/it/>

<http://www.museoarcheologiconapoli.it/it/father-and-son-the-game/>

<http://www.officinarancilio1926.com/it/progetto.html>

<http://www.participatorymuseum.org>

<http://poltronafraumuseum.it/it/>

<https://www.rijksmuseum.nl>