Introduction

Italy is the country with the highest number of festivals in Europe, reflecting the contemporary trends in tourism and the emerging demand for the arts. Nevertheless, the format is now experiencing a stage of maturity and a sort of rethinking under a sustainability optic it is likely to happen, for the risk of saturation in terms of funds, contents and audience is concrete. The sine qua non for the existence of a festival is the close relationship with place, the intimate connection with the genius loci (Archer 2006); in fact, the only way for festivals for being meaningful and attract audiences is to be rooted in their ground. When festivals are settled in their communities and hence socially sustainable, they will be potentially able to produce positive impacts of not only economic but, above all, of social and cultural nature; evaluating those impacts through a multidimensional analysis should be a priority for cultural managers and policy makers (Guerzoni 2008).

These issues have been applied to the case of the Festival Letterario della Sardegna L’Isola delle Storie, a book festival that emerged through a bottom up logic and is today one of the few regional best-practices in the cultural sector in Sardinia. In order to have an idea of the economic, social and cultural effects of Isola delle Storie on the local context, a survey was conducted with the support of the Association Isola delle Storie during the 2012 edition, including categorical questionnaires, qualitative interviews and secondary data analysis.

The research contributed in drawing some conclusions on festivals and social and economic sustainability.

Isole delle storie and its place

1. Cultural festivals

The practice of festivals is increasingly widespread, and they are getting more and more numerous in the last decades both in Europe and Italy. The success of festivals goes in parallel with the recent trends of tourism and growing preferences for short stays and city breaks. In this scenario, event tourism meets the emerging needs of modern tourists, as events and festivals become an expedient for visiting a region in a short length stay and an innovative experience of cultural consumption.

The attention of scholars in the last decade has focused on the so-called “cultural festivals” (Guerzoni 2008), or “smart festivals” (Federico 2008), defined as complex events aimed to participatory processes of knowledge sharing addressed to a non specialized audience. Cultural festivals find their roots in 1980s Anglo-Saxon inspirations such as Hay on Wye Literary Festival and the Science Festival of Edinburgh; the most well-known cultural festivals in Italy are Festivaletteratura Mantua, Festivalfilosofia Modena, Festival della Mente of Sarzana, Festival della Scienza of Genoa.

Cultural festivals represent an interesting object of analysis because of their role as a new cultural format which meets the emerging demands for the arts. In particular, they are able to satisfy an emerging segment of cultural consumers made up of individuals with a good level of education and a moderate taste for the arts, as they provide for a new way of transmission of knowledge which is based on high contents, but still accessible to the great public.

2. Putting festivals in their place(1)

On the other hand, the extreme proliferation of festivals is getting close to saturation on several levels (Agusto 2008). First, in terms of funds: in the current period of lack of public funds, the existence of hundreds of festivals in the country leads to an indiscriminate distribution of subsidies which often does not award quality. Second, also audience tends to lose interest in the format: as “the value of festivals is that of addressing to social needs with necessary answers” (Dalla Sega 2005), festivals risk to lose their meaning, if oversupplied.

In this sense, scholars agree upon the fact that only festivals which are rooted in their community constitute a valuable resource for society (Coen Cagli 2012). According to Robyn Archer, Artistic Director of Liverpool European Capital of Culture 2008, the reason why a festival should exist is to celebrate its place. Festivals which are able to activate processes of social and cultural growth are those related very much to a sense of the place, those conceived and designed according to its actual geography. In a way, by being intimately connected with the spirit of place, a festival can become expression of the genius loci, a concept which originates from classical Roman religion, that is the essence of a place, the decisive element which characterizes its culture (Norberg-Schulz 1979). Genius loci can be conceived as a specific advantage of the region, as it is rare and difficult to replicate (Trousil 2011). Hence, a festival should aim to express the vocation of a place, as it should be shaped by the genius loci.

3. Isola delle Storie: origins and history

The cultural association “Isola delle Storie” (from now on, referred to as the Association) was born in 2003 with the goal of spreading literature and reading in Sardinia. It originated from the initiative of ten Sardinian writers who proposed to an existing group of people from Gavoi to create a book festival based in the town. Gavoi is a town of 2800 inhabitants located in the geometric centre of Sardinia, in the inner side of the region of Barbagia. The first edition of “Isola delle Storie” – Festival Letterario della Sardegna” (from now on, Isola delle Storie) took place in 2004. During the years that followed, numerous parallel cultural initiatives were also launched in the region by some of the members of the Association(2).

The format is a three-days festival wholly based in Gavoi which takes place during the last weekend of June; it proposes readings, interviews and debates on topics connected to literature but also philosophy, politics, economics. The 2012 edition cost around 220 thousand Euros; 35% of the budget was financed by private sponsors, while the rest was sponsored by public institutions. In 2012, the total number of events was 32, while the number of invited speakers was 63.

Isola delle Storie has a strong local component, both in its sponsors and partners; however, it collaborates with numerous national and international organizations, and 90% of invited speakers comes from the rest of Italy or from abroad, showing its global relevance(3).

4. Genius loci and the roots of Isola delle Storie

Isola delle Storie can be defined as a hybrid festival (Izzo 2010). On one hand , it tries to satisfy an emerging segment of cultural tourism, being the first book festival in the region, paving the way for the creation of further similar initiatives. On the other hand, it is based on local cultural and historic sources, following a resources-based logic (Izzo 2010). The meaning of Isola delle Storie has to be investigated in the land where it takes place: Gavoi represents not only a physical setting, but also gives to the festival its identity, atmosphere and essence, or genius loci (Norberg-Schulz 1979). Gavoi’s genius loci, and hence the essence of Isola delle Storie, have to be found in three conceptual dimensions.

Storytelling , agora and confrontation

Sardinia has a solid tradition in the literary field. First, the region has a strong oral tradition. Storytelling and oral poetry are two traditional cultural forms in the region and strong triggers of social aggregation. Related to oral tradition is the public square – agora – the village reference point for social interactions and exchange of ideas. Second, Sardinia is a region of strong readers. For example, according to a 2011 ISTAT survey, 49% of Sardinian population has read at least one book in 2010, a + 3% difference regarding the national average (ISTAT 2011), despite the lower level of education of the region – in 2009, the percentage of people under 24 who held a high school diploma in Sardinia and Italy was respectively 70% and 75% (MIUR 2011).

Isola delle Storie represents a re-appropriation of the traditional role of agora, as it gives back to the public square its original role of reference point for social interactions. Traditionally, oral poetry contests used to be held in the agora, giving the audience the chance to interact in the debate and to express opinions. Isola delle Storie gives back to the agora its role of mediator: for example, as in the traditional poetry contests, a general theme is proposed, and speakers – in this case not poets but rather writers, journalists, politicians – are invited to develop a debate. The festival is hence structured as to create an informal atmosphere, both between public and authors, and among authors.

Hospitality and conviviality

Isola delle Storie is set in Barbagia, the mountain area of inner Sardinia which is also one of the least populated areas in Europe. The region is often associated to remoteness and diffidence because of its history: not only Cicero called its inhabitants barbarians and stubborn, but also the phenomenon of banditism was still widespread in the inner areas of Sardinia until the 1980s. After such a difficult past, Barbagia is today a hospitable and open region that still celebrates its traditions and at the same time welcomes visitors to its hospitable and friendly atmosphere. The idea of hospitality is also the focus theme of Cortes Apertas, the opening of the old yards and the discovering of traditional skills and gastronomic products. In the same way, Isola delle Storie is structured as to be warm and informal: participants often approach authors while walking in the town or eating in the same restaurant; authors live in an informal and convivial atmosphere and eat together, live in the same hotel and share contiguity and intimacy – “We have been united : writers, audience, locals”. In Gavoi visitors are dip into a unique greeting atmosphere made up of “food, informality and sharing”. Here, local traditional bands introduce readings; Fiore Sardo – the cheese produced in Gavoi – is offered in local restaurants; the photographic exhibition Istranzadura – which means hospitality in Sardinian – is displayed along the streets, showing pictures of the previous year’s speakers.

Cultural ferment, bottom up logic and collaboration

A further element which characterizes contemporary identity of Barbagia is a flourishing cultural ferment, which is translated into a vivid cultural production. This is especially true for Gavoi, that became in the 1950s a reference point for the exchange of ideas and cultural production. Not only the town stayed somehow immune to the severe regional phenomena of banditism, but was also the first town in the area to host a high school.

Following this inclination towards culture, Isola delle Storie rose through a bottom-up logic from a fertile context where cultural production was vivid. This also regards the relationship between the festival and inhabitants, for the whole community collaborates in the production of the festival, from the activity of volunteering to the actual fruition.

5. The benefits of a dense local network

Isola delle Storie is ideated and managed by the homonymous Association. However, most of those involved in the production are volunteers. The Association is both format owner and process owner: it designed the concept of Isola delle Storie and coordinates the activities to realize it.

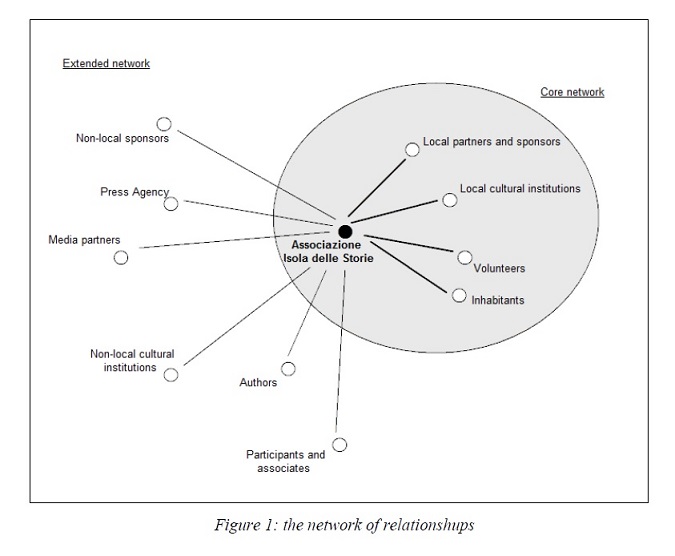

The Association holds a prominent, central role in its network of relationships, as it counts a very high number of connections. It has a glocal nature, as there exists a double network of relationships. First, the core network, where relationships are built horizontally – locally. Second, an extended network made up of actors involved in the field of culture, which evolves vertically – at non local level. In the extended network, density is very low, as the Association is the only bridge among other actors, and structural holes exist among actors within the network (Zaheer 2010).

The Association is central to both the networks, in the sense that it is in direct contact with many ties, and thanks to this it becomes visible and prominent to the other actors. The network of relationships is represented by Figure 1.

According to Klaic (2004), a small town is an ideal context for festivals: it can pool together actors and resources which will provide a lasting benefit in terms of enhanced trust, and more willingness among cultural operators to work together. However, internalization soon becomes necessary, as expectations and ambitions start to grow. This is why the existence of an international, extended network is necessary as well.

The twofold nature of Isola delle Storie network, together with its direct involvement in the local community, contributes to the creation of positive benefits for the several actors involved:

1. Formal and informal relationships are facilitated. The level of closure is very high – almost all actors are connected to one another, also due to the intimate context, typical of a small town.

2. Emotional involvement characterises relationships. Ties are strong, stable and durable. Interactions are frequent over time, as they happen even beyond Isola delle Storie. They are often based on friendship and on common vision, for actors share the same local culture.

3. Trust facilitates processes. This high level of trust facilitates agreements with economic actors by lowering the transaction costs and favouring social relationships.

4. Centrality gives access to resources. The central role of the Association gives access to local resources, both human and economic.

6. Towards and evaluation: local impacts

The relationship between festival and place can be considered somehow cyclic. To start with, Isola delle Storie is produced by its land, and hence represents Gavoi’s genius loci. Then, Isola delle Storie also produces effects in the region. The more a festival is rooted in its land, the greater the effects produced will be: “only festivals which arise from the community are able to produce benefits, while those created for mere economic purposes, without expressing an identity value, turn out to be a failure” (Coen Cagli 2012). The nature of effects is multidimensional, as they involve economic, social and cultural variables.

Methodology

Methodology was elaborated according to the main bibliography that covers the topic (e.g. BOP Consulting 2011; Impacts 2008a; Aliprandi 2011). Main tools included:

1. Press review analysis and use of national and regional statistics.

2. 153 questionnaires for participants completed by interview during the 2012 festival edition.

Questions covered demographics, economic impact, motivation for festival attendance and cultural behaviours connected to the festival. Looking at the economic impact, the total visitor expenditure was chosen as the representative economic variable. Queries included length of stay, expenses in accommodation, food, books and merchandise. Only participants from outside the province were considered for the economic impact – excluding casual tourists – leading to 110 questionnaires (71% of total visitors).

Main segments considered were:

• Excursionists;

• Guests of friends/family;

• Visitors staying in hotel (1 night);

• Visitors staying in hotel (2 nights);

• Visitors staying in hotel (3 nights);

• Visitors staying in hotel (4 nights).

Average total expense of every segment was obtained and then projected in the whole population of Isola delle Storie. To obtain the total number of visitors, data from organizers were used – vouchers are distributed at every event. However, to avoid the confusion between number of presences and actual participants, the number of total tickets was divided for the average number of events attended per person (Snowball 2004), leading to an estimated number of 6500 total visitors.

3. Qualitative interviews to specific stakeholders, conducted during the festival and in the following weeks.

Main interviewees included the Association’s Secretariat and several external stakeholders – administrators, librarians, cultural operators, operators from the hotel and food industries, inhabitants, volunteers and visitors. Around 50 qualitative interviews were raised. Interviews usually lasted from 15 to 40 minutes, and were conducted according to the methodology found in Corbetta (2000) with the support of a vocal recorder.

Economic impact

a) Direct impact

Looking at the economic side of regeneration, it emerged from the analysis that the estimated total visitor expense is 736,352 Euros, compared to 220,000 Euros of total budget and 50,000 Euros invested by local public bodies. Considering that the Municipality yearly revenue is around 4 million Euros, this means that almost 20% of the annual income is input in the area thanks to Isola delle Storie.

b) Effects on tourism

One of the most relevant aspects to look at is the long run effect on tourism. The so called Bilbao-Guggenheim effect brings to a region a publicity that “cannot be bought” (Binns 2005:4). Isola delle Storie has a crucial role in the attraction of new flows: according to provincial data on accommodation capacity of the last years, from 2006 to 2012 the total number of accommodation facilities has grown from 6 to 12, and the number of beds has increased from 202 to 353.

Gavoi has not a vocation for mass or maritime tourism, like most of Sardinian tourism destinations, and the majority of tourist arrivals are registered in Autumn and Winter. In this sense, Isola delle Storie is able to generate a new season, as it creates a peak of arrivals that is atypical for June and July. Also, when Isola delle Storie takes place, the whole capacity of accommodation is exceeded, with hotels and restaurants of the province sold out weeks in advance.

c) Effects on sales

The great majority of local economic actors agreed upon the fact that Isola delle Storie gives high economic advantages during the three days of festival: “it is the only period in the year that everything is sold out” and “normal supplies are not enough”. Also, the majority of main local actors is satisfied about advantages in terms of publicity, as “the word-of-mouth brings every year more people”.

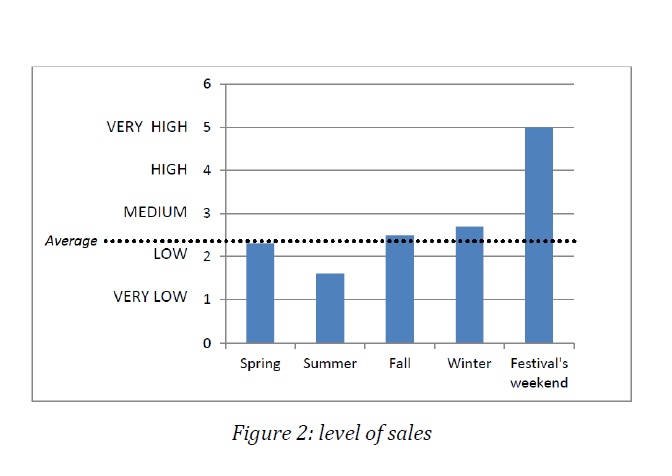

To better test which is the intensity of the advantages, it was asked to interviewees to identify a level of sales, in a scale from 1 to 5, for a random weekend of each season, plus the festival’s weekend (see Bocciero 2008).

Results, represented by Graph 2, show that Isola delle Storie brings a unique level of sales and that it raises significantly the annual sales average.

Social impacts

Social impacts are produced when social capital is combined and exchanged among actors, and new knowledge – that is, intellectual capital – is created (Nahaphiet 1998).

In the case of Gavoi, social impacts are the most significant added value connected to the festival. The main categories of individuals that participate and benefit from the exchange and creation of intellectual capital are the local community, children and volunteers.

a) Local community: cohesion and participation

The impact on local community is collective, as the effects benefit the community as a whole. Impacts are mainly expressed in terms sense of belonging and pride, increased contact with other cultures, involvement and participation in the community (Scottish Executive Education Department 2004).

First, locals have a strong sense of ownership and pride with respect to the festival: “Isola delle Storie is not just a festival based in Gavoi, it is Gavoi’s own festival”. According to Norberg-Schulz (1979), locals’ sense of pride is proof of their identification with a festival, and according to Bonetti 2009 the high level of embeddedness of local community contributes to explain social impacts produced by festivals.

Second, Isola delle Storie provides locals with the opportunity to meet people from different cultures, something especially precious in the case of an isolated context such Gavoi. The way inhabitants react to external inputs of individuals and resources is definitely positive: “the festival is unique, it brings diverse people to Gavoi; there should be many more similar events during the year”. Also, it seems to have improved the perception of the town from the residents’ eyes.

Third, levels of involvement and participation are very high: the whole town is involved in the event, and the 2800 villagers are split among those who work directly for the festival – organizers and volunteers – those who work in the touristic field – hotels, restaurants, shops – and those attending the festival. According to a great portion of UK literature (see Matarasso 1997; DCMS 2010) participation in the arts can help removing immaterial barriers such as impossibilities of literacy or exclusion from community life; In the same way, Isola delle Storie becomes an occasion for every social segment to socialize and become part of a tangible project.

b) Children

Great attention to children is given during the festival in an initiative called Spazio Ragazzi, which includes readings, laboratories and movie screenings. The three days of kermes represent the conclusion of a year-long learning path for Gavoi students: in January, laboratories and classes focused on a specific theme start, beginning an educational process which involves children and their parents.

According to scholars, participation in cultural activities at a younger age leads to increased economic capital when older, independently of social background (DCMS 2010), favouring the so-called “addiction to culture”. With this regards, in 2008 Isola delle Storie won the Andersen Prize for Childhood literature as best actor for the promotion of culture and reading because “it was able to create in a small context an annual meeting that is getting of national prominence”.

However, it seems that Isola delle Storie produces social impacts, rather than tangible effects on reading: the festival is an occasion for children to develop the so-called “non-cognitive” skills. Thanks to the festival they “can get a new approach to reality and see new possibilities of life”, and a “small anthropological miracle” happens: busy streets, stories told by lecturers transform the isolated town of 2800 inhabitants into a “harbour of people, stories and romance”. The extent to which Isola delle Storie contributes in the development of social skills is very difficult to measure; however, the involvement of children in the festival seems proven by the fact that, once they grow up and school activities with Spazio Ragazzi are concluded, 90% of first year high school students become volunteers the following year.

c) Volunteers

The 2012 edition was realized with the support of 230 volunteers. 90% of them came from Gavoi and its surrounding area; they can be equally distributed into three age categories: 13-19; 20-35 and 35-60 year old. This heterogeneity in age classes is unusual for cultural festivals, as usually volunteers are teenagers and young adults (e.g. BOP Consulting 2011), and shows the extremely high level of participation.

It seems that, for those volunteering, the main reason for participating is linked to the sense of belonging to the town: for youngsters, volunteering for Isola delle Storie is a mandatory stage of community life, the step after the experience of Spazio Ragazzi. For adults, similarly, becoming volunteers means participating to the social life of their town, feeling part of the community.

The way volunteers see Isola delle Storie is univocally positive. The experience was defined “exciting, enthusiastic, unique”. Beside the enthusiasm, also feelings of pride emerged: “it is the only occasion for Gavoi to emerge”; “we are proud of how our town becomes”.

Looking at the “cultural” impact of being a volunteer, a sort of “voluntary effect” happens, and Isola delle Storie becomes an incentive to approach reading and to come into contact with the world of literature: “youngsters get curious about authors, get interested in reading their books, asking questions. It constitutes a good approach to reading”.

Cultural impacts

a) Participants

According to Morganti (2009), it emerges from the literature that the most influencing impact of cultural festivals is the educational effect. As for Isola delle Storie, participants can be divided into two sub-groups. The first one, composed by 53% of the respondents, is made up of “cultural consumers”, as there exist strong cultural and reading habits. For this bridging social network, made up of weaker but broader bonds, the festival becomes a sort of trading zone in which knowledge and experience are exchanged.

While this is not surprising for a cultural festival, the unusual data regards the second sub group, made up of “non-cultural consumers” (around 20% of total audience). This finding shows that Isola delle Storie manages to promote cultural accessibility through a language which is understandable by everyone.

The non-cultural visitors respond to the following characteristics:

• 63% of participants from Gavoi belong to the category.

• The most diffused classes of age are 19-29 (25%) and over 60 (29%), while in the generic survey they were respectively 13% and 10%.

• The modal class for level of education is the high school diploma (graduate level in the total sample).

• Among the reasons for attending the event, the category “curiosity/atmosphere” grows to 58%, compared to 35% in the full sample, while the “specific interest for literature” decreases from 82% to 67%.

• Looking at the impact on reading, the festival becomes a way to approach reading for 13% of respondents (9% in the case of the total survey) and to read more for 32% (25% in the case of the total survey).

In other words, Isola delle Storie makes reading more accessible. It is not by chance that during the months preceding Isola delle Storie books by the authors that will be invited are sold out in the local library. This accessibility feature emerged also from the press review (Gottilieb 2010):

“Are you American?” asked me a stallholder in Gavoi, a convincing strapping man who manages a stand of typical products. In America, a man in his condition would likely be a fanatic of football and beer, and would fall asleep every night in front of his at full volume television. “What is your opinion about David Foster Wallace?” asks me. Probably I wasn’t clear. A honey seller, in a tiny little town in the middle of Sardinia, asked me what do I think about David Foster Wallace. Did I enter into a parallel universe, or it really happened? Well, yes. As someone said, God works in mysterious ways”.

b) Impacts on other cultural organizations

At local level, Isola delle Storie collaborates with the Primary School, the local library, many cultural associations and the MAN, one of the most important national museums of contemporary art in Italy. The local cultural sector benefits from Isola delle Storie as it helps developing its capacity, as well as professional and artistic skills.

However it emerged that the festival’s potential as network orchestrator is not fully exploited, as it is still missing is a network of relationship involving local museums and festivals. This is likely to be related to the lack of a stable stream of activities during the year, that could produce more effective long-term benefits and stable collaborations.

Nevertheless, Isola delle Storie contributed to the creation of a permanent network of relationships in the literary field in Sardinia, the 2012 project Liberosiv. This consists of a network that gathers together every actor in the publishing supply chain – writers, publishing houses, book sellers, libraries, literary agencies, cultural associations and festivals – to promote reading in Sardinia. Liberos, which is the first practice of “literary social network” in Italy, fully understood the role that reading has in the region as a meeting point for the community and as creator of social cohesion, economic wealth and civic awareness, embodying the existing resources in a powerful and stable network of synergies. On one hand, member book shops, libraries and festivals devote special attention to regional editors and writers, and involve other members in their activities. On the other hand, publishing houses, literary agencies and writers give priority to member libraries, book shops and festivals in their promotional activities, and provide for their network of relationships to libraries, book shops, festivals and cultural associations. Liberos promotes reading all year long all around Sardinia, and aims to create “a widespread and permanent literary festival”.

Conclusions

Today festivals assumed a crucial role in the panorama of live cultural production of Italy. The proliferation of festivals is a response to the emergence of a segment of cultural consumers who have a good level of education and who enjoy consuming culture – in the form of books, cultural events, debates on skilled topics – during their spare time. Nevertheless, considering the high number of initiatives, there is the concrete danger of saturation for the format of festivals in Italy, and the main prerequisite for festivals is to be an expression of the vocation of place.

With this regard, the research analysed the relationship between the book festival Isola delle Storie and its place, the town of Gavoi. Isola delle Storie is shaped on local identity features – i.e. the agora, the literary tradition or the hospitality of the region – leading to a solid commitment from the local community. The close social connection with place brings several benefits:

1. Isola delle Storie is doubtless an excellent activator of economic processes, not only in terms of direct economic impact but also of long term benefits on tourism;

2. The festival awakens an entire community, and the high levels of participation of every demographic and social class contribute to enhance communitarian identity and social cohesion. It also represents a reference point for local children and youngsters in their education. Considering that Gavoi is a peripheral reality both geographically and anthropologically, participating to Isola delle Storie contributes for children and young volunteers to the development of cultural and social skills;

3. Isola delle Storie represents a regional reference point both for consumers and suppliers in the cultural field. Even more importantly, it promotes reading to a non specialised public.

Nevertheless, several limitations were identified, mainly in terms of:

1. Financial and structural instability: the Secretariat works almost exclusively without remuneration, and the festival is mainly based on subsidies and public funds;

2. Precarious impacts on reading: despite the fact that Isola delle Storie contributes in an early taste of literature, reading habits among the local community seem to need a further stimulus;

3. Lack of an effective local cultural network: despite its prominent role in the regional scenario, Isola delle Storie does not fully exploit its potential of trigger of energies, as it misses to involve other literary festivals and other cultural organisations.

Future scenario/further development

What emerged from the analysis needs a further research based on solid methodological basis, looking both at the evaluation of the economic impact and the social and cultural variables involved.

However, for the purpose of this work it can be said that, after ten years of activity, Isola delle Storie is an established reference point in the regional scenario, mainly thanks to its solid social and cultural roots in the local context, but a further step should take place. In particular, the festival needs a more sustainable structure and a qualitative leap in terms of local networking in order to produce solid impacts in the cultural sphere.

In this scenario, Liberos can represent a good opportunity for a leap in quality, as it takes the next step in building a stable network of resources spread all around the region. The direction towards the establishment of a widespread and permanent “festival” seems the right one, because today festivals need to evolve from mere temporary events and acquire continuity in time in order to become able to activate more solid processes.

Endnotes

(1) The title refers to the keynote address to the British Festivals Association conference, Cardiff , October 2006 by Robyn Archer, see Archer R. (2006).

(2) E.g. Festival TutteStorie in Cagliari, Settembre dei Poeti in Seneghe, Festival di Letteratura di Viaggio in Mandas.

(3) Private sponsors are Fondazione Banco di Sardegna, Banca di Sassari; Tiscali, Cantine Argiolas, Consorzio per la Tutela del Fiore Sardo D.O.P., Ristorante Santa Rughe-Gavoi, Sa Marchesa, Moovioole, Tottue, Edilmoderna, Planet Service, Libreria Novecento and 50 local commercial activities. Public sponsors are Regione Sardegna, Municipality of Gavoi, Nuoro Chamber of Commerce, GAL BMGS, BIM. Collaborators include MAN –Museo d’Arte della Provincia di Nuoro, Università degli Studi di Sassari, Consorzio per la pubblica lettura S. Satta di Nuoro, Associazione culturale Su Palatu_Fotografia, Ipotesi Cinema, Istituto Comprensivo di Gavoi, Liberos-la comunità dei lettori sardi, Booksweb.Tv, Bibliobus, Umanitari– Cineteca Sarda, Cooperativa L’Aleph, Goethe-Institut, Istituto Culturale della Repubblica Federale di Germania, Istituto di Cultura Polacco di Roma, Istituto Romeno di Cultura e Ricerca Umanistica di Venezia, Forum Austriaco di Cultura di Roma.

Acknowledgments

The research was conducted with the help and support of the Association Isola delle Storie in 2012. The article was obtained from my Master’s thesis presented in December 2013 to the University of Bologna. It was supervised by Prof. Luca Dal Pozzolo. 21

Bibliography

Agusto G. (2008), I festival tra impatto sul territorio e luogo di espressione per l’immaginario collettivo, Tafterjournal N. 2 – Gennaio 2008

Aliprandi D., Bollo A., Gariboldi A., Oioli S. (2011), Il valore della cultura. Per una valutazione multidimensionale dei progetti e delle attività culturali, Fondazione CRC

Archer R. (2006), Putting festivals in their place, Keynote address to the British Festivals Association conference, Cardiff , October 2006

Argano L., Bollo A., Dalla Sega P., Candida V. (2005), Gli Eventi Culturali. Ideazione, progettazione, marketing, comunicazione, FrancoAngeli

Belfiore E. (2002), Art as a means of alleviating social exclusion: Does it really work? A critique of instrumental cultural policies and social impact studies in the UK, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 8:1, 91-106

Binns, L. (2005), Capitalising on culture: an evaluation of culture-led urban regeneration policy, Futures Academy, Dublin Institute of Technology

Bocciero F. (2008), Le VIE di Settembre al Borgo. La valutazione delle ricadute socio-economiche del festival sulla Città di Caserta, www.fizz.it

Bollo A. (2009), La dimensione economica del «Salone Internazionale del Libro, Economia della Cultura, Anno XIX, 2009/4, pp.557-564

BOP Consulting (2011), Edinburgh Festivals Impact Study, www.bop.co.uk

Bourdieu P., Wacquant L. (1992), An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, University of Chicago Press

Cairoli M. (1999), Il marketing territoriale, FrancoAngeli

Cercola R., Izzo F., Bonetti E. (2010), Eventi e strategie di marketing territoriale, FrancoAngeli

Coen Cagli M. (2012), Speech at ArtLab12 Plenary Session “Per non concludere” – Lecce, 29 settembre 2012

Corbetta P. (2000), La ricerca sociale: metodologie e tecniche, Il Mulino

Dal Pozzolo L., Bollo A. (2009), Quali valutazioni economiche in tempo di crisi?, in Economia della Cultura, Anno XIX, 2009/4, pp.465-472 DCMS (2010), Measuring the value of culture: a report to the Department for Culture Media and Sport, 2010

Federico C. (2008), I festival «intelligenti» e il pubblico dei giovani, Economia Della Cultura – a. XVIII, 2008, n. 1

Fondazione Cariplo (2009), Periferie, Cultura E Inclusione Sociale – Quaderni dell’osservatorio

Fondazione Fitzcarraldo (2002), Indagine sul pubblico dei festival del Piemonte dal vivo

Granovetter M. (1973), The Strength of Weak Ties, American Journal of Sociology Vol. 78, No. 6, pp. 1360-1380

Guerzoni G. (2008), Effettofestival – L’impatto economico dei festival di approfondimento culturale, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio della Spezia

Guerzoni G. (2009), L’impatto economico dei festival: un’annosa prospettiva di ricerca, Economia della Cultura, Anno XIX, 2009/4, pp.473-485

Hillman J. (1999), Politica della bellezza (a cura di Francesco Donfrancesco), Moretti e Vitali Editori

Impacts 08 (2008a), LAS Baseline and 2007 Results, University of Liverpool and Liverpool John Moores University

Impacts 08 (2008b), Volunteering for Culture, University of Liverpool and Liverpool John Moores University

ISTAT (2011), Noi Italia, 100 statistiche per capire il paese in cui viviamo, www.istat.it

Klaic D., Bacchella U., Bollo A., Di Stefano E., Hansen K. (2004), Festivals: Challanges of Growth, Distinction, Support Base and Internationalization, www.fitzcarraldo.it

Matarasso F. (1997), Use or Ornament? The Social Impact of Participation in the Arts, available at http://mediation-danse.ch/fileadmin/dokumente/Vermittlung_ressources/Matarasso_Use_or_Ornament.pdf

MIUR (2011), La bussola di riferimento dei PON Istruzione – Il trend dei principali indicatori statistici, available at http://archivio.pubblica.istruzione.it/fondistrutturali/valutazione/bussola_riferimento/pdf/Rapporto%20indicatori.pdf

Morganti I., Nuccio M. (2009) Gli studi di impatto dei festival: esperienze e riflessioni, Economia Della Cultura – a. XIX, 2009, n. 3

Nahaphiet J., Ghoshal S. (1998), Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Apr., 1998), pp. 242-266

Norberg-Schulz C. (1979), Genius Loci, Electa Milano

Paiola M., Grandinetti R. (2009), Città in festival – nuove esperienze di marketing territoriale, FrancoAngeli

Palmer R., Richards G. (2007), European Cultural Capital Report, Arnhem, Atlas

Scottish Executive Education Department (2004), A literature review of the evidence base for culture, the arts and sport policy

Snowball J.D. (2004), Interpreting economic impact study results: spending patterns, visitor numbers and festival aims, South African Journal of Economics Vol. 72:5 December 2004

The Budapest Observatory (2006), Festival-world summary report

Trousil M., Jašíková V., Marešová P. (2011), Importance of genius loci in destination management by shared vision, www.wseas.us

Uzzi B. (1997), Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness, Administrative Science Quarterly; 42, 1

Van Aalst I. (2011) City festivals and urban development: does place matter?, European Urban and Regional Studies, 19(2) 195–206, p.196

Zaheer A. (2010), It’s the Connections: The Network Perspective in Interorganizational Research, Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 24 Issue 1

Sitography

http://liberos.it

http://www.bandierearancioni.it

http://www.comune.gavoi.nu.it

http://www.eventando.it

http://www.galdistrettoruralebmgs.it

http://www.isoladellestorie.it

http://www.museoman.it

http://www.poesiafestival.it

http://www.sardegnacultura.it

http://www.unionedeicomunibarbagia.org

www.festivalfilosofia.it