Introduction

This paper aims to present the achievements of the first two years of New Creative Markets, a programme of professional development for SMEs in the creative industries in London. The programme provides valuable data on the participating businesses and freelancers, both in quantitative and qualitative terms.

New Creative Markets is a large-scale programme run by a consortium of four not-for-profit organisations: Four Corners, Cockpit Arts, Photofusion and SPACE, which is the lead partner. The programme has a total budget of £2million (about € 2,5million) and receives part funding from the European Regional Development Fund. New Creative Markets’ goal is to assist London-based small creative companies and freelancers working in photography, design, craft and visual arts to access new markets by increasing their market knowledge and business skills. The programme delivers its services through one-to-one contact and group support through workshops, talks and networking events. Activities started in October 2012 and run until Summer 2015.

New Creative Markets is a highly tailored programme designed by support specialists for creative industries practitioners. The four partners are focused on different sectors of the creative industries and offer their expertise and networks to the participants joining their programme.

This high level of tailoring is unified through a shared client journey and methodologies, common marketing and communications, as well as a high level of collaboration between partners. The requirements of running an ERDF-funded programme mean that strict controls are in place, both in the recruitment of participants and in the sourcing and delivery of activities. The client journey and corresponding paperwork agreed by all partners not only ensure that funder requirements are met by all at each step of the way, but also that data is gathered throughout the programme in a consistent and useful manner.

The data for this research is based on the forms filled in at the start and end of the programme as available in June 2014: 312 needs assessments and 91 completion reviews.

This paper will commence by introducing the context in which New Creative Markets is occurring, stating the importance of the creative and cultural sector in London. It will then present the profiles, business needs and financial performance of the participants. This paper will share the results achieved so far by the support programme, both in quantitative and qualitative terms. Finally, it will then propose different avenues of reflexion to create better programmes by bringing together an analysis of the programme data and several aspects of the current academic literature on business support.

Context

New Creative Markets was devised by four London arts organisations in order to offer an impactful programme of professional support for their audiences in different parts of the creative industries. Coming together across creative disciplines as a consortium to access ERDF funding has enabled them to offer a larger, more ambitious programme of support.

The Creative Industries in the UK are proportionally one of the largest in the world and one of the most dynamic sectors in the UK economy. It is worth £71 billion (1). In recent years, the Creative Industries in the UK have grown far faster than the rest of the economy. Employment in the Creative Industries increased by 8.6 per cent between 2011 and 2012, a much higher rate than for the UK Economy as a whole (0.7%), and now accounts for 5.6% of the total number of jobs in the UK (2). The value of the Creative Industries, measured by the GVA, has increased by 15.6 per cent between 2008 and 2012, compared with an increase of 5.4 per cent for the UK Economy as a whole (2). Finally, exports of Creative Industries services now represent 8% of all UK service exports, and have also been increasing faster that export of other UK services (2).

London plays a crucial role in the UK Creative Industries. It accounts for over 30% of the total Creative Industries in the UK (£21.4 Billion) (3). 1 in every 6 jobs in London is in the Creative Industries (3).

The creative sectors supported by New Creative Markets (Craft, Design, Photography and Visual Arts) represent an important part of the creative industries in the UK. With over 857 art galleries and high profile world events such as Frieze Art Fair, the capital is the main driver of the UK visual arts sector, which accounts for 30% of the global art market (4). London is also a main hub for the UK digital imaging sector: 39% of companies in this sector are based in London (5). 23% of UK Design businesses are based in London, making it the largest concentration of design companies in any UK region and claiming a large part of this £15bn industry (6). Finally, the size of the Craft sector in London is hard to ascertain, but the London Creative Workforce proposed that 6% of creative industries jobs can be classified as “craft” (7). We know that there are over 17,000 craft business in England and that there is a high concentration in London (8).

The creative businesses taking part in New Creative Markets share characteristics and difficulties. They are all based on content creation, artistic vision and personal expertise. They all have seen major technological changes impact how they conduct their business; but they are not, in the majority, part of the high-growth technological or digital sector. The owner’s skills in business management are recognised as a main handicap for the creative industries to realise its potential: “There is a need for access to business skills and business development training for makers, particularly at new entrant and mid-career stage” (9). Indeed, the managerial capacity in the owner-manager and his or her ability to operate in an uncertain external environment are well documented as key factors in the growth of an SME (10). Business support in the form of advice and mentoring provides much needed “reassurance in the face of uncertainty” for entrepreneurs (11). Research also indicates that the relevance of advice to the entrepreneur’s needs is central to successful support (12), including sharing experiences between peers (13).

Thus, New Creative Markets focused on addressing needs by improving the marketing and management skills of the owner-manager, while using peer-to-peer support and industry specialists to transfer specialist industry knowledge, which is generally kept tacit.

Data Presentation

• Participants Profiles

New Creative Markets reached 405 participants by June 2014. These participants come from all parts of London (27 boroughs out of 32). Photography (Digital Imaging) is the most represented discipline in the programme (53% of participants). Visual Artists make up for a quarter of the group, while Craft and Design both account for 11% of participants.

The programme participants tend to be more diverse than the average in the Creative and Cultural Industries in London: the participants are 66% female, 40% BAME (Black Asian Minority Ethnic including white non-British) and 12% disabled. By comparison, it was reported that the industry is on average 41% female, 7% BAME (excluding white non-British) and 9% disabled (16,17).

• Business profiles

All New Creative Markets participants are micro-businesses (less than 10 employees). In keeping with averages in these sectors of the creative industries, the programme participants are largely sole traders (89%) (18). 10% are owners of an SME and only 8% pay salary costs. 81% work full time on their creative business.

The average turnover from their activities as a sole trader is £14,520 (approximately €18,300). Costs are £9,837 (approximately €12,400). This combines to give average profits of £4,472 (approximately €5,600) and a Gross Value Added of £5,117 (approximately €6,500) (which includes profit, salary costs and depreciation). As most are sole traders, the profit figure corresponds to the “take home” salary for the creative practitioner from the business, a huge amount less than the UK minimum hourly wage (£6.50/hour, approximately €8.20/hour) (19).

• Business Confidence

On entering the programme, the creative businesses and freelancers on the programme were asked to rate how confident they felt about a number of issues, from whether they believe they can earn a living from their business to how comfortable they are accessing new markets or creating promotional material.

Most participants are unhappy with their current level of turnover (rated on average 3/10), but are moderately positive that they can make a living through their creative business (rated on average 6.8/10).

Participants are asked about their confidence in their marketing skills. Participants are relatively confident in reaching existing or new markets, and in their ability to present professionally, particularly the artists. Producing or accessing marketing material isn’t seen overall as a major concern, though designer makers and photographers are less confident about it.

Most creative businesses on the programme weren’t confident that they would hire somebody part or full time in the coming year. Only 18% of them were positive about hiring somebody in the next 12 months. This reflects accurately the nature of the industry, which is mainly based on sole traders.

• Needs of participants

When entering the programme, participants are asked to rate their needs in different areas. This information is crucial for programme delivery partners to tailor each step of the training journey to the needs of participants, but also to understand the needs of creative businesses in a wider, industry context.

The most pressing needs all revolved around developing sales through understanding clients and routes to markets. The exploration of needs at entry stage validates New Creative Markets’ rationale that market knowledge is the main need for creative micro businesses and confirms that the main focus for participants on the programme is to increase their turnover to sustainable levels.

Practitioners and creative businesses on the programme are then concerned with developing the capacity of their business. They valued improving their strategic skills as business managers, their marketing ability and finally their production or new product capacity. The issues of financial and legal management are last in order of importance.

This focus on sales by opposition to the issues traditionally attached to growth (IP, legal and financial management) doesn’t only show that most participants are in the early stage of their business cycle. It is also very much in keeping with research on micro businesses from all industry sectors, which shows that sustainability rather than growth is at the heart of concerns for microbusinesses (21).

Impact of the programme

• Financial performance

By the end of June 2014, New Creative Markets had delivered over 12 hours of support to 283 participants out of 405 registered (70%). Participants are asked to fill in a completion review after at least a year on the programme and completing 12 hours or more of support. The impact of the programme comes from 91 completion reviews returned so far.

82.4% of participants reported making sales in new markets, either through a new client, a new product or a new geographical market. The amount of new sales created by the beneficiaries reached £550,339 (approximately €695,000) in June 2014. This is an average of £5,234 (approximately €6,610) for each participant who made new sales. 20% had entered into international contracts or joint ventures.

Economic performance is a difficult target to achieve, as costs often increase quicker than profits. Only 54% of participants having finished the programme reported an increase of economic performance (GVA), with an average of £6,931 (approximately €8,750) each, or £361,271 (approximately €456,300) in total.

Indeed, over 80% of participants attributed to the programme a positive impact on the financial results they achieved, whether on the extent of their success or on the speed at which they achieved this.

• Business confidence

Participants’ confidence was tested both at the start and at the end of the programme. The table below shows that, after the programme, participants tend to be less confident about the future but more confident of their skills.

They reported being less confident that they will be able to sustain themselves through their business or practice, or that they will hire staff in the following year. But they exhibited an increase in confidence in their ability to reach new markets, make the most of existing opportunities, present their work professionally or access/produce marketing material.

The programme can therefore has successfully increased the business skills of the creative businesses and artists on the programme while managing their career expectations.

Fig.1: Impact of the programme of participant’s confidence

• Programme feedback

Feedback on the programme is excellent. An overwhelming majority of participants would recommend the programme to their peers (rated 9.1/10). Less than 5% of participants would not recommend it.

The programme is achieving what it set out to do with the participants: exiting participants feel that it has met their expectation and answered their need as identified at the start. They feel that it made a valuable and lasting impact on their business.

The programme has a good direct impact on the business performance of the participants. The participants feel that the programme helped them grow their business (6.74/10), access new markets (6.76/10) and develop new ways of selling (6.75/10).

Analysis

• Self-employment, Sustainability and Growth

The profiles and needs of the participants of New Creative Markets give valid indications for the Creative Industries sector at large. They represent a part of the economy rarely taken into account by the government, as most are well below the VAT tax threshold.

Being almost 90% sole traders, the New Creative Markets participants are representative not only of the Creative Industries but of a growing share of the working population.

Indeed, the Creative Industries have always relied heavily on self-employment, three times more than the rest of the economy (25). But self-employment is currently at record levels in the UK economy as an aftermath of the recession. 15% of UK workers are now self-employed: “the highest percentage at any point in the past four decades” (26). Rise in UK employment since 2008 is predominantly among the self-employed (26). This working model is thus increasingly shared beyond the creative industries.

Particular issues face the self-employed professional. Some researchers argue that self-employed freelancers are a “neglected form of small business” (27). The median income from self-employed professionals has dropped 22% since 2008/09 (26) and it is argued that they “earn less, work harder and (are) more isolated” (28). Indeed, the financial profiles of the programme participants show that most are struggling financially.

Although one of the main goals of the funded programme is to create new jobs, the main need for the participants is to “make a living”. Developing sales and market routes were the most pressing concerns of the participants. Only 8% employ staff and 18% were considering hiring employees in the coming year. But 27.7% of participants who completed the programme created work for other freelancers.

This pattern of growth without increase in size has been noted in the creative industries (29, 30), and may be linked to the business models of the creative enterprise or to the intrinsic satisfaction found in the work itself (31). But this might also be due to the size of the businesses in question rather than the industry. Research shows that owners of micro-businesses in all industries have a tendency to be lead by personal – as well as financial – objectives (32) and are resistant to traditional models of growth, including employment (21).

New Creative Markets is useful to better understand the model of business development in the Creative Industries, which may not yield many “employees per business”, but certainly represent a dynamic, and increasingly important part of the economy.

• A tailored and connected programme yields better results

New Creative Markets shows that it pays to identify and address unique sector-specific needs of the participants, and to work with participants with the long term in sight.

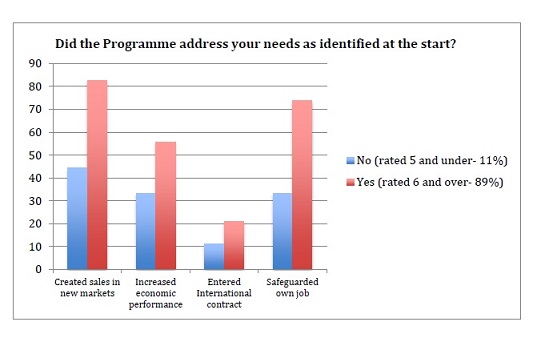

Most clients achieved results, regardless of their feedback on the programme. But a closer analysis reveals that results increase a lot when the participant feels that the programme has met his or her needs.

Fig.2: Programme tailoring and participant performance

In short, the programme performance is linked to its quality: participating businesses achieve better when their needs are well identified, and met by a tailored support.

Academic research on business support for entrepreneurs states that taking accounts of the needs in the supported businesses, as well as providing specific support and “informal support mechanisms” such as networking events are some of the main elements of an effective training and support programme (22). Indeed, peer-to-peer support is an important learning method for entrepreneurs (12), particularly in the creative industries (23).

It is not surprising then that the businesses and freelancers involved have reported that their favourite parts of the programme were the one-to-one support sessions with industry specialists, and the networking opportunities. To quote two participants:

“I left my MA a while ago, so being able to come back and receive critical feedback from a peer group, feel a sense of community and have the space to share is invaluable”

“The best thing about being on the New Creative Markets programme is contact with others… Hearing others’ stories of how they’ve come to a similar point in their career has been very helpful to me. ”

• Confidence in business skills leads to business performance

Analysis of the programme data shows that confidence in business skills is linked to better business performance in a virtuous circle. It is materialised in increased presence in new markets and increased economic performance.

Programme data shows that those who are confident in their ability to make the most of existing opportunities have created 10% more sales in new markets and 10.5% more likely to increase economic performance than the average programme participant finishing the programme.

The participants who are very confident in their ability to reach new markets are 14% more likely to have made sales in new markets and 20% more likely to have increased their economic performance than the average participants finishing the programme.

A participant exemplifies this virtuous circle in this remark: “I am feeling more confident. Obviously, results create confidence, don’t they? If I sell a piece of work, I become more confident and I will sell another piece of work”.

Management skills of the business owners have been found to be a major element in business growth (9). But a mentor-based programme has been found to provide “reassurance in the face of uncertainty” (11) rather than hard outcomes. The programme data shows that “soft outcomes” are at the heart of increased financial performance.

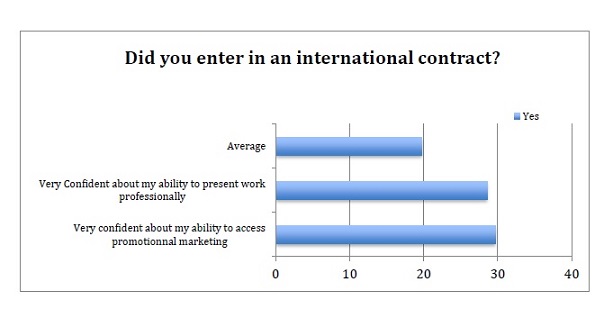

Fig.3: Business confidence and performance on the programme

• Role of Marketing Confidence in Internationalisation

The analysis of New Creative Markets data has shown that trading abroad is strongly linked to confidence in marketing issues. Participants who had a high confidence in their ability to present their business professionally and to access marketing material are much more likely to trade abroad than the average participant having finished the programme.

Those who were very confident in their ability to access the promotional marketing they need by the end of the programme were 50% more likely to have entered in an international contract or joint venture. Those who were very confident in their ability to present their work professionally to an audience or a client by the end of the programme were 44% more likely to have entered in an international contract or joint venture.

More consistency and professionalism in marketing processes has been linked to higher chances of internationalisation: “whilst reliance upon informal (marketing) methods is often adequate in some domestic markets, such methods may be inadequate abroad” (9, p115). Although creative enterprises have been shown to internationalise in different ways than traditional industries, “exploiting personal and business networks” (24), marketing confidence seems to be linked to better chances of success abroad.

Fig. 4: Marketing confidence and internationalisation

• Gender differences on the programme

The participants on New Creative Markets are predominantly female (66%). This reverses the proportion currently found in the overall sector (16) but reflects the gender ratio found in creative graduates (29).

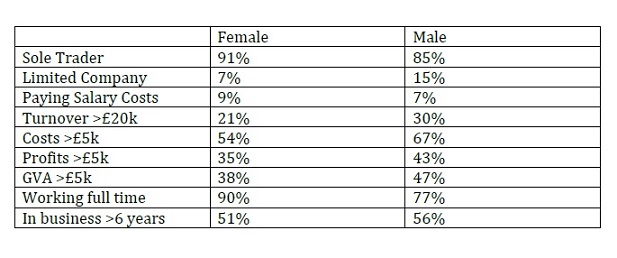

The profiles of the participants to New Creative Markets show interesting gender differences: businesses led by males are noticeably more sustainable that those led by women.

The data shows that males are twice as likely to have a limited company than females and slightly more likely to pay salary costs. Their turnover is higher, and so are their costs. Their profits are higher as well as their GVA. Males on the programme are also more likely to work full time and have been in business slightly longer.

Fig.5: Gender variation on business profile

This is consistent with gender research on entrepreneurship which finds that women “perform less well on qualitative measures such as job creation, sales turnover and profitability”” (34)

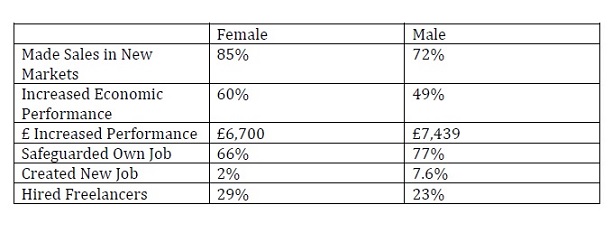

But we find that businesses led by females achieved more on the programme than businesses led by males in almost all indicators.

Female-led businesses are 19% more likely to make sales in new markets, for a higher amount. They are also 24% more likely to increase their economic performance as a result of the programme, although the average increase is higher in male-led businesses.

Male-led businesses rate higher in matters of employment: they are more likely to have safeguarded their own job at the end of the programme and are more likely to have created a new position. Interestingly, female-led businesses tend to hire more freelancers and women in self-employment have been rising at over twice the rate of males in the past five years (26).

Fig. 6: Gender variation on performance on the programme

Female participants also appreciate the programme more. They are 15% more likely to attribute a positive impact on their success to it (85.4% versus 74.4%) and 11% more likely to say that it helped their business grow. Both genders would recommend the programme equally.

Although the difference between male- and female-led businesses in the programme reflects what was previously proposed by researchers, we believe that evidencing a gender difference in performance after a support programme is new.

It could point to a greater lack of skills, but our data shows that there is little gender difference in the needs assessments at the start of the programme: female participants rated their needs only slightly higher than males (7.5%).

More research is needed in how creative women-led businesses perform on support programmes. But our conclusions so far could serve as a counter argument to those who propose that female-led businesses have goals that are less “classically” growth-oriented than men-led businesses (36,37), and point toward a particular propensity to learn and implement in this type of highly tailored, collaborative support programme.

Conclusion

New Creative Markets has been supporting creative businesses in London since 2012. This programme aims to help creative businesses in the visual arts, photography, design and craft sectors to access new markets and develop their sales. It is part-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and is delivered by four arts organisations working in partnership.

The scale of the New Creative Markets has allowed it to reach critical mass in the London creative economy: over 450 participants have already created over £500,000 in new markets and over £350,000 in increased economic performance.

The programme has allowed us to learn more about the business needs of the industry, which is of great importance for the partners involved. Understanding how to develop income streams and creating a professional marketing offer were the prime concerns of these micro creative businesses. Marketing confidence seems to be linked to an increase in activity in new markets, in particular internationally.

Further analysis of the programme data points to a virtuous circle of confidence and results, with peer-to-peer networking providing reassurance, encouragement and opportunities.

Finally, though female participants run businesses that are smaller than their male counterparts, they seem to benefit more from the programme in terms of financial performance and feedback. More research is needed to fully understand the implications of these results in a larger context.

New Creative Markets will continue to support London creative businesses until Summer 2015. A final evaluation will be conducted by an external evaluator and will provide a valuable update on this paper.

Bibliography

(1) UKTI (2014), UK Creative Industries- International Strategy – accessed 10/10/14 at

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/329061/UKTI_Creative_Industries_Action_Plan_AW_Rev_3.0_spreads.pdf

(2) BIS (2014), Creative Economic Estimates- January 2014– accessed 10/10/14 at

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/271008/Creative_Industries_Economic_Estimates_-_January_2014.pdf

(3) Greater London Authority (2014), Backing the Creative Industries – accessed 10/10/14 at https://www.london.gov.uk/priorities/arts-culture/backing-creative-industries

(4) Greater London Authority (2014), 20 Facts About London’s Culture – accessed 10/10/14 at https://www.london.gov.uk/priorities/arts-culture/promoting-arts-culture/20-facts-about-london-s-culture

(5) Skillset (2011), Photo Imaging Labour Market Intelligence Profile – accessed 10/10/14 at

http://creativeskillset.org/assets/0000/6012/Photo_Imaging_Labour_Market_Intelligence_Digest_2011.pdf

(6) Design Council (2010), Design industry Research http://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/DesignIndustryResearch2010_FactSheets_Design_Council.pdf

(7) Greater London Authority, London’s Creative Workforce 2009 Update Profile – accessed 10/10/14 at

http://legacy.london.gov.uk/mayor/economic_unit/docs/wp40.pdf

(8) Craft Council (2010), Craft in An Age of Change Profile – accessed 10/10/14 at http://www.craftscouncil.org.uk/content/files/Craft_in_an_Age_of_Change.pdf

(9) Smallbone, David and Wyer, Peter (2006), Growth and Development in the Small Business, in Enterprise and Small Business: Principles, Practice, and Policy, 2nd Edition, Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, UK

(10) Ramsden, M & Bennett RJ (2005), The Benefits of External Support to SMEs, in Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development Vol. 12 No 2

(11) Boter, H & Lundstrom, A (2005) SME Perspectives on Business Support Services, in Journal Of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol.12 No. 2

(12) Gibbs, AA (2000) SME Policy, Academic Research and the Growth of Ignorance, Mythical Concepts, Myths, Assumptions, Rituals and Confusions, in International Small Business Journal, Vol.18, No.3

(13) Creative and Cultural Skills (2009), The Craft Blueprint: A Workforce Development Plan for Craft in the UK, accessed 13/10/14 at

http://blueprintfiles.s3.amazonaws.com/1319724056-11_20_Craft-blueprint.pdf

(14) Cockpit Arts (2012), The Cockpit Effect 2012- Successful Craft Business Models

(15) British Photographic Council (2010), Industry Survey of Photographers: Full Results and Analysis

(16) Creative & Cultural Skills (2011), Creative and Cultural Industries: Impact and Footprint 2011/12

(17) Creative Skillset (2011), Sector Skills Assessment for the Creative Industries 2011

(18) Department for Media Culture & Sports (2014), Creative Economies Estimates, January 2014, Statistical Release

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/271008/Creative_Industries_Economic_Estimates_-_January_2014.pdf

(19) 2014 National Minimum Wage https://www.gov.uk/government/news/above-inflation-rise-for-national-minimum-wage

(20) AIR Big Artist Survey 2011

(21) Gray, C (2002), Entrepreneurship, Resistance to Change and Growth in Small Firms, in Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 9 (1), pp.61-72

(22) De Faoite, Henry, Johnston & Van Der Sijde (2004), Entrepreneurs Attitudes to Training and Support Initiatives: Evidence from Ireland and the Netherlands, in Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 11 (4), pp.440-448

(23) Rae, D (2004), Entrepreneurial Learning: A Practical Model from The Creative Industries”, in Education + Training, Vol 46. Nb 8/9, pp492-500

(24) Fillis, I (2002), The Internationalisation Process of The Craft Microenterprise, in Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, Vol 7, No1

(25) Baines & Robson (2001), “Being self?employed or being enterprising? The case of creative work for the media industries”, in Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol. 8 Iss: 4, pp.349 – 362

(26) Office for National Statistics (2014), Self Employed Workers in the UK- 2014, http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_374941.pdf

(27) Kitching, J & Smallbone, D (2012), Are Freelancers a Neglected Form of Small Business?, in Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol.19, No1, pp-74-91

(28) RSA (2014), 10 Take-Aways From Our New Report On Self Employment,

http://www.rsablogs.org.uk/2014/uncategorized/10-takeaways-report-selfemployment-2/#more-20821

(29) Ball L, Pollard E, Stanley N (2010), Creative Graduates Creative Futures, Council for Higher Education in Arts and Design, University of the Arts London, http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/pdflibrary/471.pdf

(30) Fillis, I (2002), Creative Craft Behaviour in Britain and Ireland, In: Irish Marketing Review, Vol.15 No1, p38-48

(31) Reijonen, H and Kompulla, R (2007), Perception of Succces and Its Effect on Small Firm Performance”, in Journal od Small Business and Enterprise Development, Vol 14 No4, pp.689-701

(32) Leadbeater , C and Oakley K (1999), The Independents: Britain’s New Cultural Entrepreneurs, Demos, London

(33) Greenbank, P (2001), Objective Setting in the Micro-Business”, in International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviours and Research, Vol.7, No.3, pp.108-127

(34) Carter S, Anderson S and Shaw E (2001), Women Business Ownership: A Review of the Academic, Popular and Internet Literature, Report to the Small Business Service, UK, http://www.bis.gov.uk/files/file38362.pdf

(35) Fenwick, T (2002), Transgressive Desires: New Enterprising Selves in the New Capitalism, In: Work, in Employment and Society, Vol 16, No 4 pp 703,724

(36) Elinor, G, ed (1987), Women and Craft, London: Virago Press