ABSTRACT

This contribution is focused on an area located in the southern area of the Lazio region called “Valle di Comino” that has valuable characteristics from an environmental and historical construction point of view. It’s part of a wider research path carried out within the Laboratory of Documentation Analysis Survey and Technical Architecture (DART) of the University of Cassino and Southern Lazio which deals with the analysis of the historical centers of southern Lazio, from architectural to environmental emergencies[1].

INTRODUCTION

The promotion of territorial networks with high historical-cultural-natural-landscape potential is a very discussed and central theme in the revitalization of large areas of Italy.

The historical value of small towns, closely related to the geo-morphological characteristics of the territory, not only preserves the values of local heritage but it’s also able to ensure a proper maintenance of the territory.

The various imbalances –settlement, functional, infrastructural and environmental –can be remodulated by shifting the focus from the only recovery of structures to the attempt to restore the territorial functions of the settlements.

These settlements are to be understood as central places of distributed territorial values.

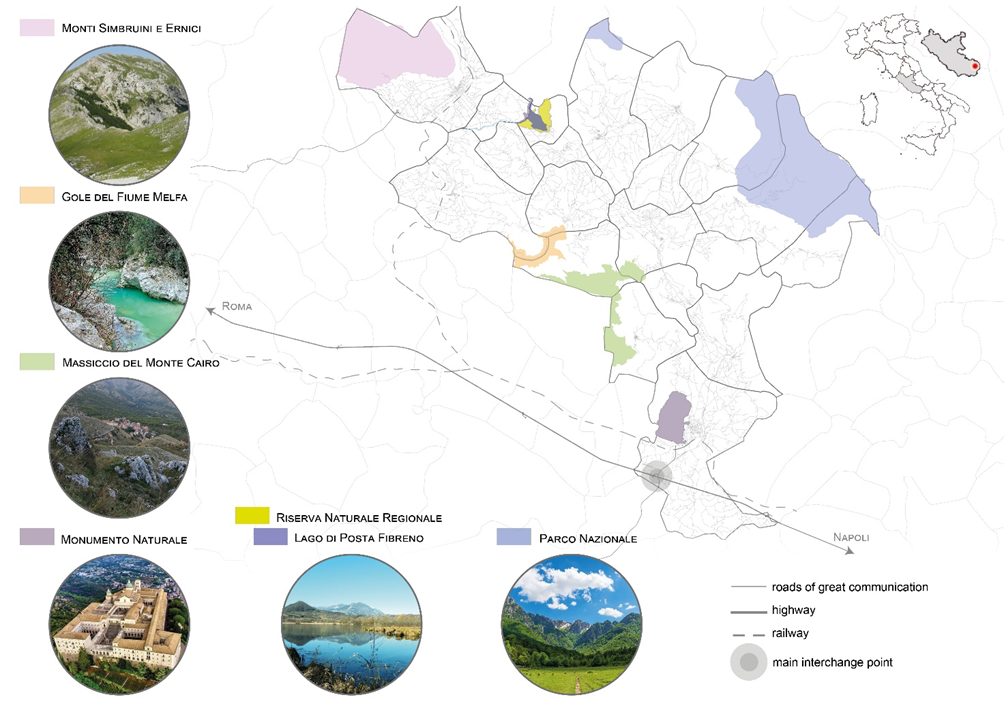

The concept of network as nodes connected in a plural way, is the main reference for intervention programs in areas of high historical-cultural and environmental value but structurally weak from a socio-economic point of view. In this complex and articulated framework, the territorial network replaces the concept of dependence between polarizing and minor centers with the concept of synergy and cooperation, in order to promote long-term strategies based on local geography economies. The Comino Valley is located in the southeastern corner of Lazio region, and it borders the regions of Abruzzo and Molise. It’s almost circular, with a total area of about 400 square kilometers, and, from a naturalistic point of view, it’s certainly one of the most interesting areas of the region (Fig.1).

The Valley is located in a strategic position, between Rome and Naples, and it includes the municipalities of Atina, Alvito, Gallinaro, San Donato Val di Comino, Settefrati, Picinisco, Villa Latina, Vicalvi, Casalattico, Casalvieri, Posta Fibreno, Belmonte Castello, Terelle and San Biagio Saracinisco.

All of these territories are characterized by a complex stratification of historical-cultural and natural values of great importance for the settled communities. The high quality of the natural environment is also recognized by the presence of several protected natural areas[2] such as the Abruzzo Lazio and Molise National Park, Mount Cairo and the mountains of Meta, and the regional Lake of Posta Fibreno nature reserve (Fig. 2). Among villages, parks, rural life, the Valley is able to narrate culture, history and stories. Despite that, complex relationships between historical, cultural, natural and settlement values of the territory are to be reinterpreted to promote the enhancement of local vocations. This can be done through a model of networked territory that allows to identify the critical issues and the potential on which to base a proposal for the enhancement of the territory.

Thanks to a Geographic Information System (GIS), used to create, manage, analyze and map all types of data, part of the territories defined as “weak” are also included in the analysis. They are identifiable as mountainous, internal and rural areas; geographical areas at risk of isolation and impoverishment. The analysis is divided into two different phases:

– the first one recognizes the different characteristics concerning the distribution of significantly descriptive values within the complex territorial system;

– the second one involves a brief interpretation of territorial values that provides a tool, useful to many stakeholders, on which to base long-term planning proposals, in order to safeguard and promote both, the vocations and the values of each place.

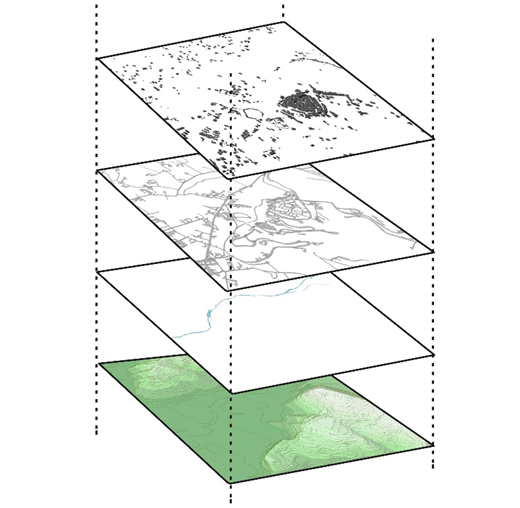

The choice of a GIS system for the analysis of this area allows professionals not only to create a faithful representation of reality, but also to place themselves as an essential element at the design level in environmental and territorial management. Among all the existing GIS software, the open-source matrix QGIS, can be used. Thanks to this tool it’s possible to face critical analysis and overcome the simple visual analysis. It also allows to connect the collected documentation to a map, integrating the data about the location (where things are) with various descriptive information (how things are there). So, it makes it possible to combine information from many independent sources and to derive new sets of information (results) by applying a sophisticated set of space operators.

Looking at changes over time, it’s possible to analyze various levels in order to calculate the suitability of a place for a particular activity (Fig. 3). This helps to understand relationships and the geographical context as well as to provide a basis for the mapping and analysis used[3].

THE KNOWLEDGE FRAMEWORK

When studying a territory, it’s necessary to analyze not only the geographical characteristics but also other parameters (physical, anthropic, economic) that are necessary to correctly represent the situation and the evolution of an area.

Through the GIS it has been possible to produce thematic maps representing the geographical distribution of one or more themes that have a precise geometric or spatial relationship with the different geographical entities (Fig. 4). Depending on whether the theme highlights a situation at a particular moment or its evolution, there are static or dynamic maps. The thematic maps are intended to offer a vision of synthesis of specific aspects of the territory. They contain physical or anthropic elements detectable on the territory, which allow a more detailed examination of a phenomenon; they also show information about the peculiarities of the territory and the transformation processes that affected it. These consist of images, drawn up on a cartographic basis which, through symbols, colors, conventional figures, diagrams, allow to show geographical links and to make qualitative and quantitative evaluations concerning the different specific phenomena of the considered places. Different products have been developed for this purpose, both for the type of representation and the scale of representation. Different methods have been used to make the variations of theme visible in space: color (e.g. a theme could be displayed in classified form through the use of chromatic scales), lines, geometric figures or symbols (the size of the symbol is usually proportional to the size of the variable).

Starting from a basic cartography, a series of thematic maps have been built. On these maps are reported useful information for those who work in the area. Using the layered organization, GIS systems have allowed the analysis of the spatial relations between the attributes of the database (information related to the geographical data) and the connection of these with the cartographic part, so they have made it possible to represent a model of the territory.[4]

The result is a survey (a cognitive framework) of the territory that has been divided into several subsystems, according to a precise hierarchy:

1) Environmental System

2) Infrastructure System

3) Settlement System

4) Social And Economic System

5) Cultural System

The morphology of the territory is strongly characterized by the presence of great altimetric differences ranging between 20 m a.s.l. and 2000 m a.s.l. and its hydrographic grid branches off covering the whole area. Much of the territory of the Valley is characterized by the presence of valuable agricultural soil, but the interpretation and assessment of soils show a fragmented development that compromises the quality of the landscape of the valley bottom whose continuity remains the central objective. The quality of the most inland agricultural areas is good, they don’t currently have a great attractiveness but could play a strategic role not only in economic aspects but also in the maintenance of natural quality and specific identities.

One of the problems of the Valley is the lack of mutual accessibility. From the knowledge framework it’s shown that the road network is dense but not hierarchical. Much is based on the vehicular part, and therefore the idea would be to improve accessibility to facilitate reciprocal internal mobility between the various municipalities. It turns out a system of roads that need to be improved.

By studying the urban morphology, we recognize the dense and compact tissues of the historical matrix of the centers, and then a scattered and filiform, newly formed, low density of soil occupation. The settlement system, at a functional level, is mainly a residential net of monuments and valuable building complexes used for tourism and as accommodation. In any case, commercial activities and urban services, of very low number, are located in the lower part of the territory, closer to the connecting arteries.

The total population of the municipalities of the Valley is currently about 19,000 inhabitants. More generally, all municipalities had a negative demographic trend over the years. By analyzing the real economic profile of the area, the first impression is the relatively modest rhythm at which the economic process takes place. Environmental and historical causes have obviously contributed to limit the evolutionary process.

The historical, architectural and archaeological heritage is extremely rich even if it’s not properly valued and celebrated by the landscape including it. The Valley has, in fact, a large archaeological, historical and monumental heritage stratified over time, testified by the presence of pre-Roman, Roman and Medieval ruins as well as prestigious villages. Such assets are subject to the risk of fragmentation, dispersion and potentially subject to loss of historical identity and testimonial value.

From the cognitive framework it is possible to bring out not only the strengths but also the weaknesses of the different landscapes analyzed, in order to acquire the necessary knowledge to create a useful tool which increases the territorial value.

The words of Adobati reflects the problem of the area: “It is a polysemic scenario that highlights the need to find a form of mapping of territorial phenomena: difficult to understand, and even more complex to govern, phenomena that can’t be represented.”[5]

The brief interpretation of the territorial values on which to base the proposal of long-term order, as a means to safeguard and promote the vocations of the places, has been led by five specific objectives:

1) Rebalancing of the main functions of the territory

2) Promotion of cultural landscape network

3) Re-organization of the road mobility system

4) Definition of the network of naturalistic routes

5) Development of hypotheses for the recovery of historic centers

ANALYSIS OF HISTORICAL CENTERS

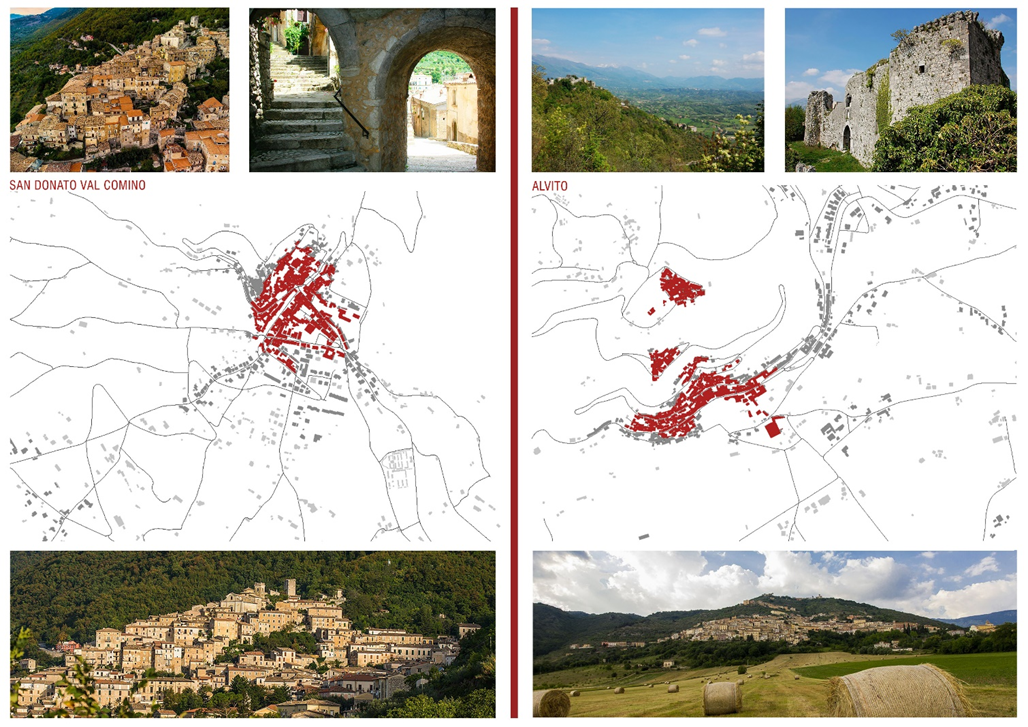

The analyzed territory is dotted with a continuous network of small historical centers integrated in an area with a strong landscape and natural values (Fig. 5). From this reflection, emerges the need to deepen the knowledge of the form of the built heritage in relation to the natural place as well as the process that has induced the formation-transformation.

The preservation of this “environmental value” must also be supported «with the idea of extending the concept of monument (understood as a significant memory of culture and therefore worthy of protection and safeguard) to the space surrounding the main architectural object, as well as to the historical settlements as a whole, long considered as “minor architecture”, unimportant and transformable according to needs».

The protection of the environmental value, as a non-renewable resource, must be related to the values of “form” of the historical building and it’s linked with the orography and more generally with the natural environment through the identification of morphological characteristics and typological values. Once the value of historical tissues has been recognized, the aim of the recovery action is to preserve this value. Of course, it’s not a question of conservation understood as a “freeze” of the existing situation, but instead of an “active conservation”, a “controlled transformation”.

The “active conservation” and the adaptation to the current functional needs – referring to the common building of the historical centers – involve the real procedural action, “the maintenance” and the acceptance of the process of formation and transformation that marks the life of historical buildings.[6]In this sense, the decoding of traditional constructive language assumes a central role, also through the alliance between “scientific knowledge” and “historical knowledge”, to propose compatible interventions oriented towards conservation. The dissemination of knowledge on historical technical construction methods, related to specific geographical realities, can be a useful tool for operators in the sector to make choices that can be evaluated only from the perspective of the project of “active conservation” or “controlled transformation” and reuse of historically defined building tissues. The goal is to transcribe the way of building in certain geographical contexts, not through abstract theoretical models, but in relation to the particular constructive characteristics of buildings and historical events that have affected them.[7] This study mainly concerned the general aspects of the history of the territory and the settlements, the vicissitudes that characterized the relationship between the different historical moments and the architectural outcomes at different scales.

The existing structures analyzed are currently fragmented and discontinuous, therefore as a hypothesis of intervention it can be conceived the identification of a network with the function of restoring and encouraging continuity between places of greater value which today are risking to lose their identity. In order to detect the common characteristics, a schedule of the centers has been made. The historic centers are mostly located between 300 and 900 meters above sea level. The topographical position of the villages is varied, so, for example, Alvito, with its characteristic horseshoe plant, is a center of slop. There are also frequent mixed-type centers, such as S. Donato Val di Comino, where the oldest part is built on a rocky spur, while the more recent cone-shaped part extends towards the main road (Fig. 6). The most recently built villages are located in the bottom of the valley and have a more regular design. From the study of urban morphologies, we recognize the dense and compact matrix of the historical centers, and then a low-density construction of recent construction.

Among the most populous centers there Atina, Alvito, Casalvieri and San Donato. The less inhabited ones coincide with the more confined ones, such as Terelle, Belmonte Castello, San Biagio Saracinisco. All municipalities have been affected by a strong depopulation over the years. Being an area interested in an agricultural-mountain economy, this depopulation of the Comino area could be seen as a simple consequence of economic development in other sectors – as well as the result of an increasing population ageing. In fact, the demographic structure of the population, in line with national data, shows a progressive ageing and a constant reduction in the smaller age groups, in particular in countries with a low share of resident foreigners.

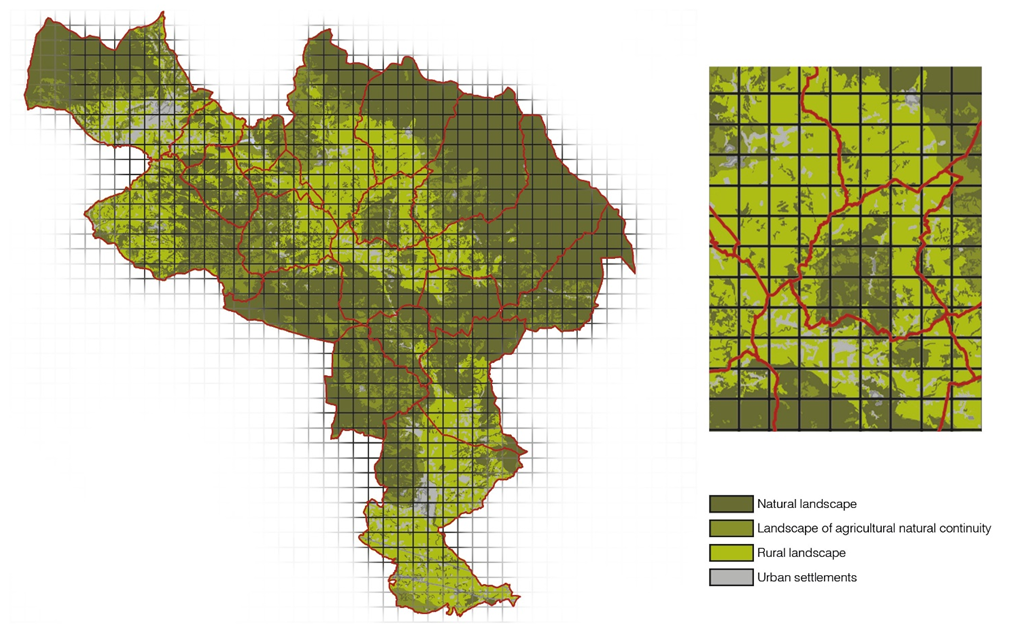

In order to recognize the spatial planning geographies of the complex territorial area, the significant variables were interpreted and recognized through the use of a regular geometric support that was able to reveal the structural invariants of the territories of the Comino Valley. The breadth and variety of forest cover, the extent and value of agricultural areas for planting and complex crop systems, lakes and minor hydrographic networks, as well as the settlement structures have been measured and recognized through a regular grid side 1kmx1km (Fig. 7). A sort of “centuriatio” that allowed to interpret in their entirety the existing systems highlighted by the preliminary analysis. This methodology was used to analyze systems which are structuring and determining for the identity of the territory. It also produced, for each system, a reading model that through a graphic abstraction reflects and describes the territory in its specificity reducing the distortion of the topographical elements.

- The green system

The use of the grid has made it possible to identify how the green system is positioned on the territory by identifying different situations especially in relation to altitude; most of the territory, in particular the highest band, is characterized by wooded vegetation. In the valley, instead, we find the fragmented presence of orchards, vineyards, chestnut groves and mainly olive groves.

- The building system

The system of the historical building and the new consolidated settlement system are also structured according to the elevation trend and in particular: in the higher altitude are found the historical settlements, dense, of medieval character; while in the lower one the settlement fabric is of more recent construction and characterized by a sparse matrix with less compactness and density.

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis highlighted a territory that has potential and criticality, whose only way to compete without distorting, preserving and promoting the morphological characteristics, is to interact in a community way through a network system. Currently the Valley has weak territorial characteristics because the modes of operation tend to separate its ancient unity. This is mainly because the smaller centers are too weak not to suffer the centrality and the polarization of the other larger neighboring countries.

A careful reading of the territory and its centers leads to the discovery of strengths and weaknesses that can come out of a S.W.O.T.[8] analysis, indispensable tool to understand the goodness of the method and to focus the crucial points in order to make decisions (Fig. 8). Only the deep knowledge of the existing allows the elaboration of strategies of safeguard and promotion that, being effectively calibrated on the local characteristics, are able to stem the criticalities, enhancing the strengths.

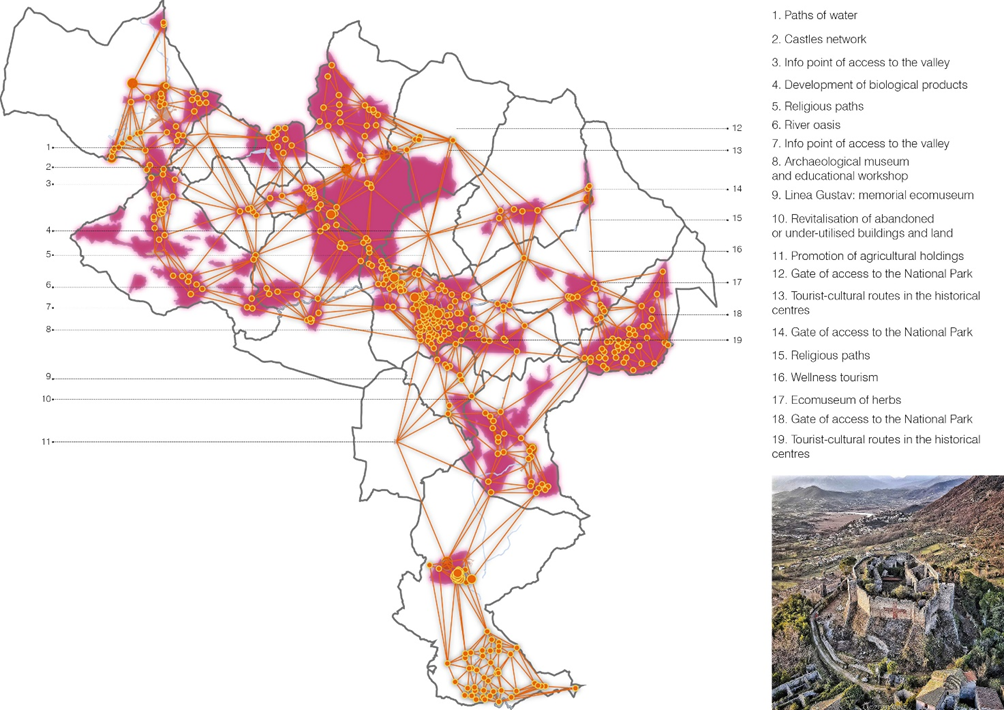

This analysis showed the prevailing presence of weak resources that badly compete with the most attractive territorial systems. It highlights the need to make the Valley an integrated system “network” through which compete with major centers. The cultural network is then reconstructed through the values currently recognized as pre-eminent; in particular the water system, the archaeological and monumental heritage, the historic centers of the municipalities and the agricultural areas. The net, defined by relatively large meshes, is rather polarized towards Sora and Cassino (the two nearest major centers), along with an arch overlooking the Abruzzo side of the National Park of Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise (Fig. 9).

The potential of a natural and cultural landscape network tends to constitute a more complex system of use of the Valley. A system of enhancement of the archaeological, monumental and architectural heritage of minor type can be imagined, and it could be included in the system of circuits of use along with some projects, with the aim of enhancing agricultural areas, already recognized of potential natural value, which intercept the main lines of development of this network. Projects of agricultural valorization together with projects of valorization of a significant part of the woods recognized as a “gate” of the National Park, strengthen the cultural net.

The net which originates changes, thickens and generates a greater number of paths and therefore opportunities of usage (Fig. 10). The developed analyzes, allow to re-read the territory at present through a reticular model. The promotion of this network takes place through the identification of sub-networks of environmental, infrastructural and settlement themes to reorient the hierarchical and geographical model towards a new network model. In this network, horizontal relations between anthropogenic values prevail while vertical relations with the landscape are ensured homogeneously by the whole Valley.

The analysis carried out allowed the following hypotheses to be developed:

– the enhancement and strengthening of the Valley’s routes to maximize its resources and values;

– the restoration of the value of continuity between significant areas, such as significant natural and rural areas, forests, identifying areas of reconstruction of nature;

– the identification of the local vocation of each country or group of countries in order to allow the circuit operation based on the orientation of local values to be promoted;

– the localization of a functional enhancement plate in privileged accessibility condition.

Finally, we reconfirm the extraordinary functions of representation of territorial phenomena, through GIS applications, which allow to analyze in a unified system diversified multi-criteria aspects to define suitable solutions and proposals for management and intervention.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adobati F., 2008 – Geografie Volontarie. Dal territorio disegnato al disegno di territorio, ARACNE.

Beranger E.M., 1980 – Testimonianze archeologiche restituite dall’agro atinate II serie.

Caira L., Orlandi V. – L’approvvigionamento idrico di Atina in età Romana, Amministrazione provinciale di Frosinone-Assessorato alla cultura.

Cedrone D., 1998, Il catasto di Gallinaro 1743, ciclostile.

Leti Messina V., 1973 – La Val di Comino. Problemi e propositi per una pianificazione intercomunale.

Macioce V., 2017 – Turismo Culturale. La Valle di Comino Incantata, Vanni Editore.

Mancini A., 2004 – La storia di Atina, parte I e parte II, ciclostile.

Marsili R., 1965 – Note antropogeografiche: la Val di Comino, Istituto di geografia Università di Roma.

Regione Lazio, Deliberazione 28 maggio 2019, n. 322 – Programmazione 2014-2020. SNAI

Tanzilli S., 2016 – Cassino, architettura archeologia arte storia, ciclostile.

Tullio P., 1994 – North of Naples, South of Rome, Hamish Hamilton -London.

Van der Maarel S., 2019 – Una guida visiva di terra incognita, biblioteca di Atina.

XIV Comunità Montana, 1991-95 – “Valle di Comino-Atina” – Piano di sviluppo.

XIV Comunità Montana, 1995 – Indagine bio-ecologica sui corpi idrici della Valle di Comino (1995).

Zordan L., Bellicoso A., De Berardinis P., Di Giovanni G., Morganti R., Le tradizioni del costruire della casa in pietra: materiali, tecniche, modelli e sperimentazioni. Firenze: Alinea Editrice 2009

SITOGRAPHY

https://www.esri.com/it-it/what-is-gis/overview

PHOTO REFERENCES

https://www.ciociariaturismo.it/

FOOTNOTES

[1] This contribution represents a synthesis and elaboration of the Master’s Degree thesis work entitled “La Valle Di Comino. The territorial vocations and the valorization of the local resources” carried out with the supervisor Professor Barbara Barboni within the Urban Planning Laboratory of the Engineering Faculty of Tor Vergata.

[2] Lazio Regional Authority has established a system of protected natural areas. The protection of these areas helps to preserve the great heritage of biodiversity and geodiversity together with the rich historical and cultural heritage, and promotes the sustainable development of agricultural activities as well as the maintenance of traditional craft activities in order to create an exponential growth of tourism.

[3] https://www.esri.com/it-it/what-is-gis/overview

[4] UNITÀ L3. CARTOGRAFIA TEMATICA, NUMERICA E SISTEMI INFORMATIVI GIS. Copyright © 2012 Zanichelli editore S.p.A., Bologna [5927]

[5] Adobati F., 2008 – Geografie Volontarie. Dal territorio disegnato al disegno di territorio, ARACNE.

[6] Zordan L., Bellicoso A., De Berardinis P., Di Giovanni G., Morganti R., Le tradizioni del costruire della casa in pietra: materiali, tecniche, modelli e sperimentazioni. Firenze: Alinea Editrice 2009 (p. 7-9)

[7] Ibidem, p. 10.

[8] SWOT analysis is a strategic planning tool used to assess Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of a project or in an enterprise or in any other situation where an organization or individual has to make a decision to achieve a goal. The analysis can cover the internal (analyzing strengths and weaknesses) or external environment of an organization (analyzing threats and opportunities).