Abstract

The city of Liverpool has undergone repeated processes of urban transformation and urban regeneration over the last half a century. The city has been a test bed for urban experimentation with mass clearance, housing, and relocation schemes in the 1970s followed by culture, event, and heritage-based regeneration strategies from the 1980s through 2000s. Following the perceived success of the 2008 European Capital of Culture and city centre Liverpool One development, an even larger, longer-term, and more expensive development was proposed – Liverpool Waters. Yet unlike its antecedents, which were consciously woven into existing urban fabric and combined multiple strategies and funding schemes simultaneously, the Liverpool Waters approach envisioned a tabula rasa disconnected from its surrounding context and which would also introduce new building typologies to the city – the skyscraper. This article examines the long-term history of urban regeneration in the city and nearly ten-year process of negotiations and redesigns of Liverpool Waters that ultimately led to the deletion of the Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City site from UNESCO’s World Heritage List. This case provides valuable lessons for cities seeking to implement large-scale urban regeneration schemes and the need for strategic and contextually sensitive approaches.

1 – Liverpool: a city of urban regeneration

Over its 800-year history, Liverpool has endured various economic ups and downs. In the 20th century alone, it has gone from being considered the ‘New York’ of Europe to the ‘Detroit’ (Belchem & MacRaild, 2006). Heavily bombed during WWII, the city struggled to recover and subsequent loss of industry related to reduced port activity took additional tolls on the city, leading to the eruption of social conflicts, notably in the 1981 Toxteth riots (Frost et al., 2011). This background has seen the city transformed into a long-term test bed of various urban regeneration schemes, from the highly invasive to the strongly integrated and, finally, the most recent and speculative Liverpool Waters. This paper reviews this long-term trajectory of urban regeneration to examine how the differing approaches have interacted with and ultimately impacted Liverpool’s built environment. This overview provides a basis from which to frame the differences in the approach of designing and developing Liverpool Waters, an ongoing large-scale urban regeneration scheme which has already been responsible for the city’s loss of World Heritage status. This case provides valuable lessons for Liverpool itself along with other cities seeking to implement large-scale urban regeneration schemes and the need for strategic and contextually sensitive approaches.

Following clean-up and rebuilding efforts, the first major urban intervention following WWII was a slum clearance program, one which saw the demolition of many existing working-class neighbourhoods, largely populated by Welsh and Irish immigrants. These initiatives saw tenement housing replaced with modern tower blocks – destroying both the physical and social makeup of these neighbourhoods. This attempt at improving the conditions of the city after war, ultimately only led to the increased loss of Liverpool’s urban fabric in addition to what was already destroyed during WWII. While these measures succeeded in reducing the housing burden on the city, they perhaps went too far as 36% of the city’s housing stock was lost – leading to a housing boom in the new towns that sprung up outside of Liverpool (Hatton, 2008; Murden, 2006). These efforts, combined with the loss of manufacturing and port-related jobs, led to significant social upheaval, gaining national attention following the 1981 Toxteth riots (Frost et al., 2011). These events would in turn lead to the next phase of the city’s regeneration, one which would focus and highlight the city’s heritage and culture.

As an alternative to the Thatcher government’s approach of managed decline of Liverpool, Michael Heseltine was nominally appointed as the ‘Minister for Merseyside’ and headed the Merseyside task Force (MTF) and partnered with the existing Merseyside Development Corporation (MDC) (Couch et al., 2011). These entities aimed at improving Liverpool and the Merseyside area through a new approach focused on leisure and tourism. Some of the high-profile projects included the International Garden Festival in 1984 as well as the restoration and reuse of the historic Royal Albert Dock. This historic building was a technological marvel when it opened in 1846 for the use of cast iron, brick and stone in the structural materials and later addition of the hydraulic cranes (Jones, 2004). This new plan overturned previous proposals to demolish the structure and instead re-used the historic structure as a new mixed-use commercial, residential and leisure centre that included the first Tate Gallery branch in 1988 (Biddulph, 2011; Meegan, 2003). This period saw an entirely new approach to regeneration, one which put culture and heritage at the centre (Bianchini & Parkinson, 1993), an approach the city would return to in subsequent phases of revitalization.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, Liverpool had yet to successfully turn around trends of economic and population decline. The city was thereby eligible for European funds, successfully receiving both Objective Two and subsequent Objective One funds (Sykes et al., 2013). While these funds were initially dedicated to the areas considered most in need of investment, the second phase concentrated on revitalizing and promoting the city centre. Due to the alignment of political, institutional and private initiatives, the late 1990s and early 2000s witnessed a far greater strategic approach to tackling the city’s problems. While earlier approaches consisted of largely one-off, disconnected big projects, this new approach resulted in a far more coordinated and integrated approach to bring together multiple plans, projects and funding schemes (Jones, 2020). A conglomeration comprised of the North-West Development Agency, English Partnerships, Liverpool City Council and Liverpool Vision cooperated to invest heavily in the city centre to create a new identity for the city and move beyond its yet tarnished reputation. These efforts included applying for UNESCO World Heritage Status, bidding for the 2008 European Capital of Culture (ECoC), the restoration of historic city centre neighbourhoods and the private retail development Liverpool One (Jones, 2019).

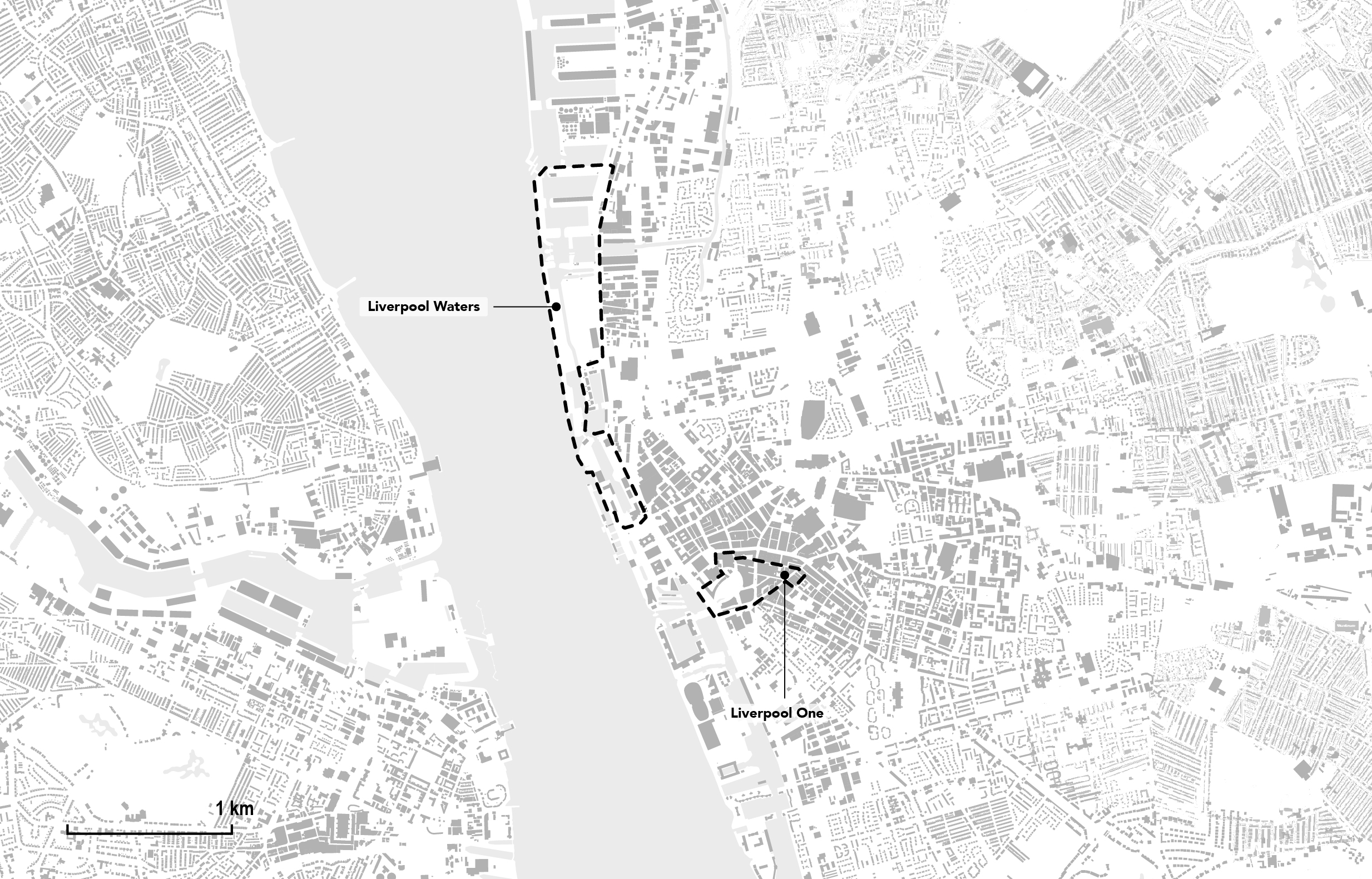

This period of Liverpool’s regeneration was largely considered to be successful, with the city obtaining both UNESCO World Heritage status with the Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City site and the 2008 ECoC. Though the ECoC would eventually come to overshadow the achievement of the World Heritage Site (Jones, 2020), there was a high level of synergy between the other elements, notably with the completion of the 17 ha and nearly £1 billion Liverpool One commercial district sped up in order to align with the celebrations of 2008. A series of themed years leading up to 2008 were also organised to celebrate various aspects of the city’s culture and heritage (García et al., 2010). Additionally, the Liverpool One complex, though located directly in the city centre, was carefully designed to respect existing street patterns and urban forms, effectively blending in and ‘disappearing’ into the existing urban fabric. The individual structures were all designed by separate architects to create a denser and more diversified core that reflected the existing city centre. These projects and policies were accompanied by the City Centre Movement Strategy (CCMS) which invested in the public spaces and transport network in the city centre, pedestrianizing streets and making the city centre more attractive and accessible. While the 2009 International Financial Crisis may have dampened some of the legacy of these efforts, the city did finally reverse decades-long trends of decline and depopulation as well as generate a new image for the city (García et al., 2010; Sykes & Brown, 2015). In the subsequent phase of regeneration, Liverpool would, in some ways, become a victim of its own success.

2 – Development of Liverpool Waters

Despite this high level of coordinated activity and investment in regenerating the city centre during the early 2000s in conjunction with its heritage, the city’s World Heritage Site was put on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2012. This demotion was not the due to any of the activities carried out, but rather due to a not yet existent but newly proposed development: Liverpool Waters. Despite the previous efforts, which largely highlighted and benefited the city’s heritage since the 1980s, the newly planned Liverpool Waters development was deemed a significant threat to the city’s Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). Developed by The Peel Group, the plans for Liverpool Waters were approved by the Liverpool City Council in 2011 and represent a drastically new approach to urban regeneration at a scale not before seen in the city. Unlike previous regeneration approaches discussed above, Liverpool Waters envisioned the creation of an entirely new district of the city, largely independent and separate from the existing city fabric. The project is a £5.5 billion proposed scheme that covers 60 ha located in and around Liverpool’s historic Northern docks, several times larger and costlier than the earlier Liverpool One development. Importantly, the Liverpool Waters site is located entirely within the boundary and buffer zone of the World Heritage Site. Most of this area is currently abandoned and unused. However, it was not the regeneration or reuse of this area that elicited concern from UNESCO. Rather, it was the proposed introduction of a new architectural typology that constituted the main threat: the skyscraper.

The proposed plans have a long-term outlook with an estimated 30-year implementation timeline; thus, the problematic skyscrapers may never come to fruition, yet their continued presence in the visions and plans retained Liverpool on the list of World Heritage in Danger. Construction works began in 2018 and as of 2022, only two of the residential buildings have been completed. The eventual site is expected to contain a mix of residential, commercial, retail and sport facilities (Peel L&P, 2022). The proposed plans are by no means fixed as they have been repeatedly redesigned over the years with a range of promotional images used to depict the hypothetical development. Like most large-scale developments, it is impossible to predict their final form as they undergo constant revision and adjustments depending on the success of each subsequent phase of the project along with more general factors such as the general performance of the economy or the developers themselves. The plans do not ignore the question of heritage and early materials even highlight the site’s heritage and claimed to aim at ‘celebrating’ Liverpool’s heritage (Peel Group, 2018). The project eventually intends to restore several of the docks, port gateways and iconic Victoria Clock Tower. These areas have been entirely closed off for decades and inaccessible to the public, so the plans by Liverpool Waters would on one hand make a large part of the World Heritage Site accessible to the public for the first time, bringing them back into use. However, due to the ongoing plans, and particularly the later inclusion and approval of the new Everton Stadium at the Bramley-More Dock in 2021 led UNESCO to delist the Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City site. The following section will discuss in greater detail the heritage discussion, debate and controversies surrounding the Liverpool Waters development that led to the eventual delisting.

3 – Heritage controversies

Challenges to the Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City emerged shortly following its listing in 2004 with the first Reactive Monitoring Mission taking place in 2006 (UNESCO, 2006). This mission took place in response to the development of the Mann Island area and the Museum of Liverpool, located next to the iconic Three Graces. This report found no imminent danger with the proposed project designs, but that potential threats may exist, particularly regarding the functional and visual integrity. This reactive mission would represent just the beginning of Liverpool’s troubled World Heritage Site as there was a gradual phasing out of heritage expertise and planning during this period (Jones, 2017). According to Rodwell (2015), the conflict emerged in part from the initial state party’s nomination referring to the value of the urban landscape, a term which was later omitted in the eventual UNESCO inscription, resulting in two different understandings of the site’s OUV. The 2011 Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach developed by UNESCO would come to recognize the importance of historic layering and connections between the different eras of development of cities, seeking to unify historic cities as a whole (Bandarin & Van Oers, 2015). However, in the case of Liverpool, a clear divide was generated between the protection of heritage and the creation of new developments, and this sense of cohesive layering promoted in HUL did not form the basis of discussion in reference to Liverpool Waters.

This creation of a false choice between protecting heritage on one-side and development on the other was furthered by local development interests (Kenwright, 2016) and politicians alike, particularly by Mayor Joe Anderson who referred to World Heritage status as a “certificate on the wall in the Town Hall” (Liverpool Echo, 2012). Surrounding and supporting these aggressions towards the protection of the city’s heritage was a general lack of proper communication and education of the value of the city’s World Heritage Site since its listing in 2004 (West, 2022). By 2011, UNESCO officially states Liverpool Waters as a threat to the OUV due to the density of proposed high and mid-rise towers, requesting that the Liverpool City Council reject the plans and carry out further reactive monitoring missions. With the plans instead subsequently approved in 2012, UNESCO shortly thereafter inscribed Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City on the List of World Heritage in Danger with the possibility of future deletion from the World Heritage List if plans were not significantly altered. This decision led to a 9-year stalemate between Liverpool, Liverpool Waters and UNESCO.

During this period, the plans and visual representations for Liverpool Waters were subjected to redesigns – the final form of Liverpool Waters remains unknown. The masterplan will be regularly updated as it is further designed and implemented. During this period, the most controversial element – the 50-story Shanghai Tower – was at first reduced in height but now no longer appears in the latest schemes. Additionally, three Heritage Impact Assessments (HIA) were carried out by the Liverpool City Council, Peel Group and English Heritage. Not surprisingly, the three investigations came to differing results – with LCC and Peel found that the development would actually benefit the city’s heritage while English Heritage found it to represent a threat. In their analysis, Patiwael et al. (2020) found that a total of 44 criteria were used between these three HIAs, but there were 11 points that English Heritage did not investigate. The three approaches also differently considered issues such as putting abandoned structures back into use as well as the creation of new public spaces within the scheme. While LCC and Peel gauged these as a benefit, while English Heritage did not consider them in their assessment. Ultimately, the three HIAs served to back the position of the entity conducting it. Local community groups such as Engage Liverpool also conducted several participatory meetings to build support for the World Heritage Site and to prevent its deletion (Engage Liverpool, 2019). During the 43rd session of the World Heritage Committee, a building moratorium on the Liverpool Waters site was declared until local plans and policies were approved by the World Heritage Centre, thus any new constructions would put the property at further risk. With the approval of the new Everton Stadium located at the Bramley-Moore dock within the Liverpool Waters Site in 2021, UNESCO officially deleted Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City from the World Heritage List.

4 – Conclusions

Of the three sites that have ever been removed from the UNESCO World Heritage List, the Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City represents the only urban heritage site to be removed. It therefore stands as a vital example for other urban World Heritage Sites around the world as they continue to face challenges from ongoing and future large-scale urban regeneration projects. As discussed in the first section, the history of Liverpool itself provides a number of alternative regeneration approaches that were either heritage-led or at least integrated with the surrounding historic areas. The earlier Liverpool One in particular stands out as a clear counter example showing that large-scale urban development master plans need not necessarily be framed as a threat with an ultimatum to choose between heritage or development, as later occurred the case of Liverpool Waters. However, the example of Liverpool Waters shows the need for planners and developers to be well aware of heritage sensitivities, risks and regulations early on in the process as subsequent attempts to adapt or alter design details later on may not be enough to reduce the potential threats.

While the development is still ongoing, it may take several decades to know the full impact of Liverpool Waters on the city’s heritage as it may yet go through several future phases of re-design. This example also raises questions as to the actual implementation of the HUL approach, both on behalf of planners and site managers to implement it and UNESCO in terms of rendering decisions based on this framework. Such precedents of deleting a site risk to reinforce false dichotomies of cities having to choose between protecting their heritage and urban regeneration, particularly as the originally highlighted concern of introducing skyscrapers into the site were no longer relevant to the final decision. Additionally, the loss of the World Heritage Site may have unforeseen consequences on Liverpool more broadly, whether in terms of a reduction of tourism and subsequent economic performance or in a changing attitude in terms of the competences and image of the city as a whole. At the time of the ratification of the World Heritage Convention in 1972, threats from new urban developments were quite common – fifty years later it is clear that such threats continue to persist and there is a need to ensure that regeneration efforts do not put heritage areas unnecessarily at risk.

References

Bandarin, F., & Van Oers, R. (Eds.). (2015). Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage. John Wiley & Sons.

Belchem, J., & MacRaild, D. (2006). Cosmopolitan Liverpool, in: J. Belchem (Ed.), Liverpool 800, pp. 311–392. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Bianchini, F., & Parkinson, M. (1993). Cultural policy and urban regeneration: the West European experience. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Biddulph, M. (2011). Urban design, regeneration and the entrepreneurial city. progress in planning, 76(2), pp. 63–103.

Couch, C., Sykes, O., & Börstinghaus, W. (2011). Thirty years of urban regeneration in Britain, Germany and France: The importance of context and path dependency. Progress in Planning, 75(1), pp. 1–52.

Engage Liverpool. (2019). Engage with the UNESCO WHS. Retrieved September 14, 2019, from https://www.engageliverpool.com/projects/engage-with-the-unesco-whs/

Frost, D., Phillips, R., Tinsley, G., Barnes, D., & Boyle, M. (2011). Liverpool’81: remembering the riots. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

García, B., Melville, R., & Cox, T. (2010). Creating an impact: Liverpool’s experience as European Capital of Culture. Liverpool: Impacts 08.

Hatton, B. (2008). Shifted tideways-Liverpool’s changing fortunes. Architectural Review, 223(1331), pp. 39–50.

Jones, R. (2004). The Albert Dock, Liverpool. Great Britain: Ron Jones Associates.

Jones, Z. M. (2017). Synergies and frictions between mega-events and local urban heritage. Built Heritage, 1(4), pp. 22–36.

Jones, Z. M. (2019). Policy and Practice Integrating cultural events and city agendas: examples from Italian/UK practice. Town Planning Review, 90(6), pp. 587–599.

Jones, Z. M. (2020). Cultural Mega-Events: Opportunities and Risks for Heritage Cities. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kenwright, L. (2016). UNESCO World Heritage Status: Flourish or Freeze. Lawrence Kenwright. Retrieved from http://lawrencekenwright.co.uk/unesco-world-heritage-status-flourish-or-freeze/

Liverpool Echo. (2012). Liverpool Council leader Joe Anderson says city would sacrifice World Heritage status for Liverpool Waters scheme in New Year report. Liverpool Echo. Retrieved March 10, 2016, from http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/liverpool-council-leader-joe-anderson-3354111

Meegan, R. (2003). Urban regeneration, politics and social cohesion: The Liverpool case. Reinventing the city, pp. 53–79.

Murden, J. (2006). “City of change and challenge”: Liverpool since 1945, in: J. Belchem (Ed.), Liverpool 800, pp. 393–485. Liverpool University Press.

Patiwael, P. R., Groote, P., & Vanclay, F. (2020). The influence of framing on the legitimacy of impact assessment: examining the heritage impact assessments conducted for the Liverpool Waters project. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 38(4), pp. 308–319.

Peel Group. (2018). Liverpool Waters: From concept to creation. Liverpool.

Peel L&P. (2022). The Neighbourhoods. Retrieved September 2, 2022, from https://liverpoolwaters.co.uk/about/

Rodwell, D. (2015). Liverpool: Heritage and Development – Bridging the Gap?, in: H. Oevermann & H. A. Mieg (Eds.), Industrial Heritage Sites in Transformation: Clash of Discourses, pp. 29–46. New York and London: Routledge.

Sykes, O., & Brown, J. (2015). European Capitals of Culture and Urban Regeneration: An Urban Planning Perspective from Liverpool. Urbanistica, (155), pp. 79–85.

Sykes, O., Brown, J., Cocks, M., Shaw, D., & Couch, C. (2013). A city profile of Liverpool. Cities, 35, pp. 299–318.

UNESCO. (2006). REPORT OF THE JOINT UNESCO-ICOMOS REACTIVE MONITORING MISSION TO LIVERPOOL–MARITIME MERCANTILE CITY, UNITED KINGDOM. Paris.

West, T. (2022). Liverpool’s European Capital of Culture legacy narrative: a selective heritage? European Planning Studies, 30(3), pp. 534–553.