Abstract

The paper deals with the phenomenon of company museums and its contemporary evolution in Italy. Such cultural centers, extending their presence in most of the territory and market sectors, arise today as a powerful identity medium for companies and brands representing Made in Italy worldwide.

The state of art in the sector will be discussed with reference to a panel of companies affiliated with the Italian Association of Company Archives and Museums (Museimpresa), standing as the major national network in the sector.

1. Introduction

Corporate museums arise today as a powerful identity medium for companies and brands representing Made in Italy worldwide. At the beginning of the new millennium, such cultural centers, preserving and communicating the Italian economic history, are extending their presence in most of the country and market sectors. They define a very fragmentary universe (indeed, a still largely underground “dorsal” of Made in Italy culture), but also an investment which could support the cultivation of innovative quality relationships among companies, territory, and society.

From this scenario, the paper aims to offer a synthetic overview of the phenomenon concerning company museums and its contemporary evolution within the Italian context, where it appears to be unique for both dimensions and its qualitative features if compared with the international scenario. Indeed, this means also to reflect about the special affinity which seems to exist between museum format and the essence of Made in Italy culture, rising nowadays internationally as a strategic communication discourse.

To this end, some general considerations will be discussed concerning the overall state of art in the sector and, in particular, the experience of those companies strategically investing in the preservation of their own historical heritage, which are owners of one or more museums today affiliated with the Italian Association of Company Archives and Museums (Museimpresa). Some empirical data have been analyzed concerning the profile of companies and their own museum offering and, when possible, compared with the findings provided by the main national surveys which have been conducted in Italy after 2000 (in particular, Amari, 2001; Bulegato, 2008).

2. The Italian scenario

2.1. Company museums system in Italy

For a long time and up to a recent past, the industrial heritage of Italian companies has been often considered an unproductive memory capital and, thus, dispersed and bloted out.

At a later stage, the Eighties and Nineties have seen a strong rediscovery of the industrial culture in Italy, as a source of values for both companies and society. A raising public attention to such topic is testified by a wide specialized literature, which both scholars and sector professionals have improved in the fields of company museology and archive-keeping especially in the first decade of the new Millennium (AA.VV., 2007 & 2008; Bonfiglio-Dosio, 2003; Bulegato, 2008; Gambardella, 2013; Negri, 2003), in continuity with the first pioneering studies developed in the second half of the Nineties (Amari, 2001; Kaiser, 1998, 1999 & 2001).

In the Italian context, multidisciplinary studies have investigated the phenomenon of company museums according to both a humanistic and economic approach, since the first scientific contributions in the museography and museology field have been flanked by a growing number of management and communication researches, in particular highlighting the special role played by the museum in the communication of corporate identity and heritage (Gilodi, 2002; Martino, 2013; Montemaggi & Severino, 2007). Furthermore, several empirical surveys have quantified the phenomenon and monitored its evolution at both the national and the local level, in order to take a census of the Italian company museums system and the its distinctive expressions (Bulegato, 2008; Manzato, Prandi & Tullio, 2008; TCI, 2008): such surveys are due to depict a very dynamics scenario, as company museums represent in Italy a widespread phenomenon distinguishing the Italian case in the international scenario.

In particular, since the Nineties the number of new industrial museums opened to public, as well as that of company historical archives, has been without equal in Europe. The most recent national survey (Bulegato, 2008) has documented a relevant extension of company museums’ system in comparison with a previous monitoring of the sector, conducted in 1997 (Amari, 2002). In detail, according to that survey, in 2008 Italy hosted 573 industrial museums: this wide universe could be internally classified as 143 corporate museums (belonging to as many single companies) and 80 collective ones (expression of local economic traditions), in addition to 222 thematic collections and 128 archives-collections. Moreover, such numbers offer an incomplete cross section of the phenomenon, because they include neither the many centers created after 2008 nor the group of small and micro projects which are only partially recognizable as real company museums or collections.

2.2. The Italian Association of Company Archives and Museums

In Italy, both public institutions and the major historical companies are nowadays participating in a real cultural movement promoting, at both the local and the national level, the protection, conservation, and valorisation of Italian industrial heritage (Martino, 2013; Montemaggi & Severino, 2007; Rossato, 2013). Indeed, several projects have been launched in this field, especially after 2010, in order to link in networks the multiplicity of industrial archives and museums which are widespread on the Italian territory according to their belonging to specific sectors or local productive districts.

Local and thematic networks have been launched in many regions (Martino, 2013): Emilia Romagna and bordering areas (Motor Valley project), Marche (Paesaggio dell’Eccellenza association), district of Omegna (household products), Veneto (historical archives and museums). Similar initiatives also involve, in the North of the country, the provinces of Milan (Milano Città del Progetto project), Parma (Food Museums), and Biella (network of fashion and textile archives).

At the national level, Italy stands among only a few European countries (such as, for example, Portugal) promoting a specific association in the sector. The Italian system of historical archives and museums is valued by Museimpresa, the already mentioned Italian Association of Company Archives and Museums founded in 2001 in Milan by Assolombarda and Confindustria, which are the two most influential associations representing the national industrial sector. In order to promote the Italian industrial heritage, the association works to disseminate both guidelines and best practices: its missions include the conservation of companies’ material and immaterial heritage; the accreditation of the role played by museums and historical archives within wider cultural and social corporate policies; not least, the promotion of industrial tourism connected to company sites and cultural centers.

The members of Museimpresa have increased in number from the 15 companies that collaborated on the launch of the project in 1999, to the over than 50 which are affiliated today. In spite of some relevant absences and a certain replacement over time, corporate members offer an exemplar summa of the most ancient family businesses representing Made in Italy tradition (Giaretta, 2004; Rossato, 2013).

Among the affiliated companies, it is possible to mention the Ferrari Museum in Maranello (Modena), a real “pilgrimage” destination for the brand’s fan community which is leader, for visitors number, at the national level (TCI, 2008). Other museums, often associated to real global “lovemarks”, have increased their international public by this way supporting their own brands’ marketing and PR strategies: among them, Alfa Romeo (Arese – Milano), Ducati (Bologna), Ferragamo (Florence), Piaggio (Pontedera – Pisa). Not least, the deep South of the country hosts a lively structure such as the “Giorgio Amarelli” Museum, created in 2001, which Amarelli’s family wanted to dedicate to the history of liquorice in Rossano (Cosenza).

Some of the largest Italian company archives also participate in Museimpresa: among them, the Olivetti’s historical archive in Ivrea (Turin), Pirelli’s in Milan, and Enel’s in Naples. Among the best practices in the sector, Eni’s historical archive in Pomezia (Rome), opened in 2006, also deserves a special mention: recognized as “of remarkable historical interest”, it preserves not only the history of the ex-State-owned company, founded in 1953, but also the one of the oil industry in Italy, by means of a 5 km collection of documents and corporate movies (Latini, 2011).

3. Some reflections starting from Museimpresa network

3.1. Companies’ and museums’ profile

Museimpresa, standing as the major Italian network of company museums, offers an expressive cross section of such phenomenon and its evolution in the country. Main background data concerning its members have been collected and analysed according to the information provided, on and off line, on the association’s official website (www.museimpresa.com) as well as by affiliated companies and museums themselves.

The collected data are limited to a few structural aspects concerning companies’ and museums’ profile and main activities; thus, their analysis aims to represent a pure preliminary step toward further systematic and in-depth investigations (see, for example, Castellani & Rossato, 2014). However, it can offer an overview of the major best practices nowadays recognizable in Italy, referring to a selected panel of companies which have chosen a specific associative commitment in order to value their own heritage and museums.

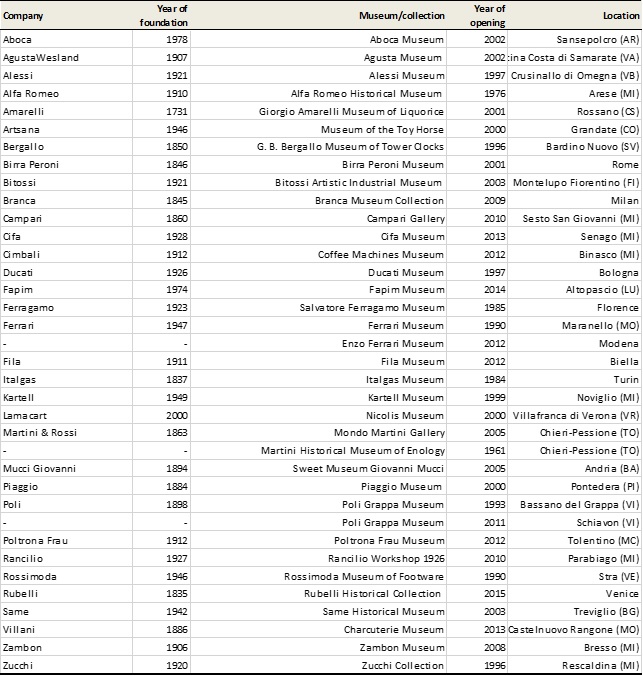

In detail, in September 2015 a group of 54 companies participates in Museimpresa association, in addition to 4 corporate supporters (National Archive for Company Cinematography, Olivetti Historical Archive Association, Isec Fundation, and Leonardo da Vinci Museum of Science and Technique). Among the members, it is possible to count a total of 36 visitor centers which can be strictly defined as industrial museums or collections, because of a continuous expository and front office activity (see Table 1).

Company museums and collections affiliated belong to 33 companies, if we consider among them the presence of some brands managing even more than one museum: these are Ferrari, which decided to add to its first famous corporate museum in Maranello (1990) a new one in Modena (2012), dedicated to the memory of its founder Enzo Ferrari; then Martini & Rossi, the well-known multinational beverage brand offering, in the province of Turin, both an enological museum (1961) and a corporate one (2005), today integrated in a wider “Casa Martini” corporate project; and Poli, a historical producer of grappa which created in the province of Vicenza two different museums celebrating the company core business, by opening the first one in Bassano del Grappa (1993) a¬nd the second in Schiavon (2011).

Not all the companies represented by Museimpresa are proud of a relevant historical tradition, as their age stretches from a minimum of fifteen years to nearly three centuries long. For more than half (18, exactly), they can be fully defined as historical companies, as they are proud of an at least centennial tradition (generally recommended by the major sector associations) and, very often, of a family ownership which is deep-rooted in the territory (Rossato, 2013). In the subgroup of historical companies, it is possible to recognize some organizations which are very ancient such as, in particular, Amarelli (founded in 1731), Rubelli (1835), and Italgas (1837), as well as some brands standing among the most well-known icons of Made in Italy tradition worldwide, for instance Alfa Romeo, Eni, Ferrari, Piaggio. Only one museum refers to the name of a no more living company: this is the “G. B. Bergallo” Museum of Tower Clocks, conserving the collection of Bergallo’s family operating a manifacturing workshop in the province of Savona from 1860 to 1983. At the same time, it is interesting to notice that nearly half of the panel (15 companies) is less than one century old, even including three realities which are younger than forty-five years: Lamacart (2000), Fapim (1974), and Aboca (1978).

Big and small-medium companies affiliated operate in the most typical business sectors of Made in Italy tradition, often connected to low and medium-innovation manufacturing. In particular, nearly one third of the museums affiliated with Museimpresa represents the food & beverage tradition (10 museums), whit a strong concentration of wines and spirits historical producers (Birra Peroni, Campari, Martini & Rossi, Poli, Branca); the remaining centers quite equally distribute among furniture and design (8), motors (7), and fashion (5). At the same time, also some companies are present which are addressed to innovation and technologies: among them, Agusta Wesland (aeronautics and motorcycle sector), Cifa (machinery for concrete), Fapim (accessories for doors and windows), Italgas (gas distribution), and Zambon (chemistry and pharmaceutical industry).

Company museums represented by Museimpresa are very varied also for their age. Both the two most long-standing institutions are located in the province of Turin: these are the already mentioned Martini Historical Museum of Enology, founded in 1961 in Chieri-Pessione, followed over time by the Alfa Romeo Historical Museum in Arese, created in 1976 and recently restored and reopened to public. Then, during the Eighties, just two centers among those affiliated were opened, such as Italgas Museum in Turin (1984) and Salvatore Ferragamo Museum in Florence (1985). Confirming the trend observed at the national level (Bulegato, 2008), the launch of new museums (as well as their buildup) visibly becomes more intense over time: in particular, among the 36 company museums analyzed, 8 were created during the Nineties, 13 in the following decade (2000-2009), and 11 just in the five years after 2010.

Concerning their territorial location, company museums represented by Museimpresa reside in different Italian regions, distributing from North to South and reproducing the industrial geography of the country. Indeed, confirming the findings provided by previous survey (Bulegato, 2008), most of museums concentrate in the North of Italy (27, that is more than two thirds of the panel), and in particular in Lombardia (11 museums), Veneto (6), Piemonte (5), and Emilia Romagna (4). As predictable, the most represented city is Milan and its province, hosting 9 expository centers as well as the headquarter of Museimpresa association itself and most of its corporate supporters. Conversely, only a limited number of museums is represented from the central regions (7), in particular from Tuscany (5), and just two affiliated centers are located in the South of Italy: the Sweet Museum “Giovanni Mucci” (Andria, Bari) and the Liquorice “Giorgio Amarelli” one (Rossano, Cosenza).

3.2. Company museums’ formats and offering

With a few exceptions, the museums affiliated with Museimpresa association stand as real corporate ones (Martino, 2013), since they focus on the history of single companies and are strictly addressed to developed a strategic brand storytelling, starting from two typical features: a title evoking their owner brand and an in-house location (Bulegato, 2008). Other centers are dedicated, in the title, to the memory of single businessmen; some of them show also the features of more “polyphonic” industrial museums, sublimating a company’s history in that of its own territory or productive sector.

It is also interesting to notice a small group of centers which have chosen to explicitly give up the traditional definition of “museum” or “collection”, for adopting a more appealing positioning. It is possible to mention, above all, the more flexible “gallery” model (in the middle between a permanent institution and a more ephemeral event), proposed by two very dynamics centers such as Campari Gallery and Mondo Martini one; moreover, within the group of affiliated companies, also Rancilio distinguishes itself for defining its own visitor center as a permanent “workshop” (Officina Rancilio, 1926).

The museographic formats are very heterogeneous. The expository area stretches from a minimum of 140 m² (Sweet Museum “Giovanni Mucci”) to a 6.000 m² surface (Nicolis Museum of vintage cars and historical motoring by Lamacart). Two thirds of the museums (24) are up to 1.000 m² wide, while, as predictable, they tends to grow in extension above all in the motors sector where for instance, in addition to the Nicolis Museum, also the Alfa Romeo and Ferrari ones stand.

Company museums’ activity is not always continuous; at the same time, the comparison with previous national surveys (Amari, 2001; Bulegato, 2008) suggest it is becoming more stable over time. In particular, if today most of museums (21) are opened permanently to public, daily or according to specific opening times, for more than one third (15) they are accessible only for appointment. Just one third (12 museums) requests visitors an entrance fee, while the access is free for the remaining centers.

Service offering is very various too. In all the cases, guided tours are available, usually by prior arrangement, also in English or in other foreign languages. More than half of the museums annexes also a bookshop or a giftshop. In some cases, museum centers also include meeting halls, educational workshops, cinema theaters, restaurants, and other facilities for their visitors, such as for instance factory tours.

In particular, about half of the museum centers analyzed are strategically connected to the company historical archive, playing as the major scientific keeper of company tradition and providing cultural materials for museum collections themselves. More than one third of the museums offers also a library annexed, which is accessible for the public. In comparison with previous surveys (Bulegato, 2008), such findings illustrate a more stable integration of the museum as the core of a richer cultural offering, including also company historical archive, library, and other facilities, and attributing the museum a preeminent role in the overall public relations strategy.

Not least, at the communicative level, two thirds of the museums (24) have developed a dedicated website, usually valuing a rich multimedia and iconic language, even if this is not always available in English and other languages. In some cases (for instance, Ducati and Peroni), dedicated websites host a real virtual museum tour, reproducing visit experience on the web. Conversely, one third of the analyzed museums show a less pronounced presence on line: those centers do not manage an autonomous website, while they can be reached through their own companies’ website where specific sections or just single pages are set up.

4. Made in Italy from myth to history. Final considerations

Company museums phenomenon is not at all new, since its origins date back from the late Nineteenth century (Coleman, 1943; Danilov, 1991 & 1992), but rather strongly emerging in Italy during the last decades (Amari, 2001; Bulegato, 2008). In particular, a new trend started from the Eighties and Nineties sees museum imposing as a strategic investment on corporate culture and brand heritage, in order to institutionalize company presence on territory by conserving and communicating the history of industrial organizations and businessmen (Martino, 2010 & 2013).

The state of art represented by Museimpresa shows that, in the new millennium, the phenomenon is rapidly extending along the territory and also among companies which are not so ancient. There is no doubt that, applied to the national economic system, the phenomenon of company museums expresses special strategic opportunities: it highlights an enormous symbolic and communicative potential, which is capable to distinguish the Italian productions and to help both big and small-medium companies globally compete. Furthermore, such rediscovery of the industrial culture appears of special interest in the year of World Expo 2015, because such a mega-event can represent an unique occasion consecrating worldwide the reputation and heritage of Made in Italy.

At the same time, company museums still identify in Italy a very discontinuous system, characterized by a multiplicity of expressions and an irregular territorial distribution, seeing a strong concentration of these centers in the North of the country, within specific industrial districts, and among the most long-standing companies. On the one hand, if compared with the recent past (Bulegato, 2008), most of Museimpresa’s members represent undisputable best practices, since they strongly invested in innovating their own museum formats and reinforcing the relationships with the territory and stakeholders. On the other hand, several company museums affiliated seem to be still far from strategically communicate and, in particular, fully use the potential of both the traditional web and the new participatory platforms for relating with their publics: conversely, those channels could represent today a great and low-cost showcase for promoting Italian companies’ heritage worldwide and, above all, toward a young public.

From such scenario, the findings which have been above discussed, limited to a small but selected panel of company museums, suggest once more the opportunity of further national surveys in order to monitor the dimensions characterizing the phenomenon and, above all, its qualitative expressions and innovation trends. Indeed, the most recent national survey has been conducted in 2008, thus offering a no more update overview of a phenomenon which has rapidly grown and changed especially after 2010. In-depth case studies themselves often tend to focus on the same group of companies and experiences, which have been already recognized as major best practices in the sector, while scientific investigations seem more rarely to explore other “minor” and more innovative case histories both at the local and international context, in order to review the new and strategic potentialities of the sector.

Indeed, company museums offer themselves as a powerful narrative context for products and brands interested in cultivating quality relationships with the territory and surrounding environment. They are due to safeguard and transmit to present generations an extraordinary heritage of products, symbols, and above all stories belonging to the Italian industrial tradition (Bettiol, 2015; Calabrò, 2015): family business, persons, design, arts, innovation and technology, communication, as well as landscape and towns, community relationships, and responsibility.

From this point of view, to most of the Italian companies, still find difficult to communicate their own identity in order to globally compete, company museums suggest above all the opportunity of investing in a new and more credible hi-storytelling, called not to invent stories but rather to rediscover with authenticity company roots and identity (Martino & Lovari, 2015). This actually represents the best meaning of Made in Italy: not an rhetorical commonplace, or a pure brand image to spend in the international competition, but conversely an inexhaustible source of cultural contents and values deposited over time. From this point of view, museums have actually much to teach all companies, and not only the ancient and biggest ones, about the essence of Made in Italy and its contemporary challenges.

Table 1 – Companies affiliated with Museimpresa association and their museums

References

AA.VV. (2007). Musei del Gusto. Mappa della memoria enogastronomica. Pescara: Carsa.

AA.VV. (2008). Impresa, memoria e patrimonio culturale. Economia della Cultura. Special Issue, 4.

Amari, M. (2001). I musei delle aziende. La cultura della tecnica tra arte e storia. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Bettiol, M. (2015). Raccontare il made in Italy. Un nuovo legame tra cultura e manifattura. Venezia: Marsilio.

Bonfiglio-Dosio, G. (2003). Archivi d’impresa. studi e proposte. Padova: Cleup.

Brunninge, O., Kjellander, B., & Helin, J. (2009). Corporate Museums, Memoralization and Organizational Memory. Paper for 5th International Critical Management Studies «Organizational Memory, History, and Forgetting», University of Warwick, 13-15 July.

Bulegato, F. (2008). I musei d’impresa. Dalle arti industriali al design. Roma: Carocci.

Calabrò, A. (2015). La morale del tornio. Cultura d’impresa per lo sviluppo. Milano: Bocconi.

Castellani, P., & Rossato, C. (2014).On the communication value of the company museum and archives. Journal of Communication Management, 18, 240-253.

Coleman, L.V. (1943). Company museums. Washington: The American Association of Museums.

Danilov, V.J. (1992). Corporate Museums. Galleries and Visitors Centers. A Directory. Westport: Greenwood.

Danilov, V.J. (1991). A Planning Guide for Corporate Museums, Galleries and Visitors Centers. Westport: Greenwood.

Gambardella, C. (2013). Museografia d’impresa. Firenze: Alinea.

Giaretta, E. (2004). Vitalità e longevità d’impresa. L’esperienza delle aziende ultracentenarie. Torino: Giappichelli.

Gilodi, C. (2002). Il museo d’impresa: forma esclusiva per il corporate marketing. LIUC Papers, 101. <www.biblio.liuc.it/liucpap/pdf/101.pdf>.

Kaiser, L. (Eds.) (1998). I musei d’impresa tra comunicazione e politica culturale. La memoria nel futuro. Milano: Assolombarda.

Kaiser, L. (Eds.) (2001). Musei e archivi d’impresa: il territorio, le imprese, gli oggetti, i documenti. Milano: Assolombarda.

Manzato, E., Prandi, A., & Tullio, C. (Eds.) (2008). Valori di marca. Musei, collezioni e archivi d’impresa. Treviso: Regione Veneto-Unindustria.

Martino, V. (2013). Dalle storie alla storia d’impresa. Memoria, comunicazione, heritage. Acireale-Roma: Bonanno.

Martino, V. (2010). La comunicazione culturale d’impresa. Strategie, strumenti, esperienze. Milano: Guerini.

Martino, V., & Lovari, A. (2015). Cultivating media relations through corporate memory: the experience of heritage brands. Paper for 22nd International Public Relations Symphosium – BledCom 2015, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, July 3.

Montemaggi, M., & Severino, F. (2007). Heritage marketing. La storia dell’impresa italiana come vantaggio competitivo. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Negri, M. (Ed.) (2008). Atti del Convegno Europeo dei Musei d’Impresa 2008, Milan, 14-15 Novembre.

Negri, M. (2003). Manuale di museologia per i musei aziendali. Soveria Mannelli: Rubettino.

Nissley, N., & Casey, A. (2002). Viewing corporate museums trough the paradigmatic lens of organizational memory: the politics of the exhibition. British Journal of Management, 13, 35-45.

Rossato, C. (2013). Longevità d’impresa e costruzione del futuro. Torino: Giappichelli.

TCI (2008). Turismo industriale in Italia. Arte, scienza, industria, un patrimonio culturale conservato in musei e archivi d’impresa. Milano: Touring.