Introduction

The topic of the importance of being able to measure the impact (or better yet, the plural impacts) that cultural heritages and activities have on many different areas is one of the most discussed issues in Contemporary Economic literature. There are many reasons explaining such an interest: first of all it is important to remember that during the last previous decades the well established dichotomy between the cultural world and the economic system has lost most of its more radical aspects. In addition to this, the belief that culture plays, in our contemporary society, a role that intervenes through a systemic approach, has gained an increasingly widespread acceptance.

The rise of this systemic approach was made possible thanks to the evolution of the Urban System, during the 20th Century, and in large part was due to the affirmation of new way of thinking, in which the city is considered as a whole, as an organism. Furthermore, the development of ICTs and other cutting edge technologies (such as Big Data whose potential is not yet totally explored) has rendered the relationship between culture and urban development an even closer one.

Today, mainly in the area of Management Studies, a peculiar company policy known as Corporate Social Responsibility (European Union), has seen its importance grow exceedingly. The approach of the CSR is one that permits to extend the well-known ‘accounting system’ of the companies to more social, environmental, and energetic fields of interest, finally outweighing the traditional financial and economic boundaries of the surpassed balance sheets.

This phenomenon, that has gradually established itself among the USA’s Public Companies, has still not been able to find a good level of acceptance and adherence in the Small and Medium Enterprises- the main dimensional category for Cultural and Creative Industries.

Despite the fact that these new perspectives and methods (an easier way to measure the impacts of culture and CCIs) have been affirming themselves more and more, a standard accounting system for this class of impacts is still not available today. The absence of such a standard accounting system causes unequivocally the substantial impossibility of being able to compare the foreseen results of two different cultural operations or interventions.

The importance of the need to spread a standard methodology in the accounting of social and economic impacts of the different cultural heritages, interventions and projects, represents one of the main milestones in the achievement of a more sustainable approach to culture. On one hand it could allow policy makers to compare different projects following the trade-off theory, simplifying the diffusion of a general Meritocracy that bases itself upon certain fixed figures. Furthermore, it could help Cultural Organizations to adopt efficiency-driven processes, so as to gain an improvement in the aggregated impact on territorial base.

Which culture to measure

One of the main difficulties in the application of an Economic Measurement Approach to culture is the huge diversification of cultural forms and implementations. As an accepted interpretation would remind us, cultural goods can be easily differentiated (by their support) into cultural property and cultural intangible heritage. For cultural property we mean a “movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage” (Unesco). Analysts should develop a different measuring framework for each of these kind of cultural heritage assets.

While measuring the impact a cultural festival has, for instance, one should take into account the different categories of variables that are generated from said impact in a cultural heritage. Having said this, one could also prove that the social, touristic, and economic impact of an archaeological site should be measured in a different way to which one could measure the foreseen externalities (that could be generated, for example, by the construction of a new Contemporary Art Museum in an underdeveloped urban area).

Cultural Immovable Heritage produces a direct value on the real estate industry of the local economies. As shown by recent events, the setting up of a museum can cause a positive effect on the real estate prices of the area. This, in turn, could improve the general wellbeing of the inhabitants of the area, could create a stronger touristic brand and could cause the growth of both the economy of the agglomerate and an increase in local entrepreneurship.

This kind of knock-on effect still isn’t sufficiently proved, but research shows some results in specific case-studies: among them, it could be useful to mention that the opening of Mass Moca museum in North Adams, Massachusetts, generated an overall improvement in real estate value of 14 million dollars (Center for Creative Communicty Development). Other studies show how this mechanism has even more relevance on the value of real estate in cases in which the Cultural Heritage Building is inscribed into an old town center. (Lazrak, Nijkamp, Rietveld, & Rouwendal, 2013) These experiences highlight the reasons why the usage of Cultural Heritage Buildings in Urban Regeneration Processes is so widely extended. On the other hand, it is important to underline how these processes could generate a negative impact on the lives of the inhabitants of a given area, a negative impact that could generate phenomena of gentrification (Coppola, 2012).

Intangible cultural assets show important differences in the way they create an economic improvement in local areas: these kind of assets rarely produce a direct effect on the value of real estate; more commonly they create big and immediate social and economic effects. There is an abundance of literature regarding the topic of Festivals: these events create temporary effects on the local microeconomic structure, but they are also able to produce longer effects in the development of a given area, re-evaluating whole urban areas and representing autonomous touristic attractions. This is the case of Sonar Festival for Barcelona and the Sziget Festival for Budapest. In this field of study the case of other mega-events such as the Olympic Games or Universal Exhibition is also included. All these events, thanks to the relevant dimensions of the investments, can produce sizable changes in National Accounting.

In measuring intangible assets the key variable to evaluate is the Order of Magnitude of Investment: when a Festival, for instance, is not big enough to interest a national economy, appraisals of the total impacts are not so easy to determine. Furthermore, convincing hypotheses have to be formalized both in regard to the territorial extension of the effects caused, and in regard to the identification of said effects in the overall yearly changes.

On the other hand, when an event can be identified as a Mega-Event, usually the ex-ante and ex-post evaluation differ significantly from each other, determining in fact a substantial non-comparability among the different studies, a non-comparability that is based on both the methodological premises of the aspect and on the results expressed.

Methodologies

In the last years, researchers and practitioners have developed different tools that could help organizations measure the impact on society of some kind of cultural goods or cultural activities. Although they’re not yet standard methods, these tools represent an extremely good practice for those organizations that work within the Cultural and Creative Industries Cluster.

The reliability of the results achieved through the usage of these tools is based on the capability of an organization to successfully identify the variable to evaluate, and the precision said organization is able to achieve in the field of measuring techniques and analysis procedures, set up specifically to evaluate the disaggregated results.

There is also another important element on which a good measurement process must be founded: the readyness of our organization to admit both the successes of measuring and the failures. Technically speaking, it is important to note that without the proper intellectual honesty and the desire to become accountable, every measurement risks only to become a mere excuse for an organizational activity, provoking the substantial invalidity of the measurement itself.

The most important measurement methods could be differentiated on the base of what kind of cultural goods they intend to measure: the tools that the Global Report Initiative has developed are addressed to the measuring of the impact of entire organizations, while the SROI (Social Return on Investment) extends its applicability to other projects. Another tool could also be extremely useful when measuring economic impact, but its application is still scarce in cultural economics: this tool is the Input-Output Model. It is a tool used for the measuring of the impact that a project or a building can create on satellite activities. This method allows analysts to predict the range of the impact in a given territorial area, taking into account the interdependencies shown by the different clusters that operate within.

Global Reporting Initiative

Corporate Social Responsibility is a wide phenomenon affecting the overall activity of an organization. There are numerous methods with which this company policy may be applied, but one of the most common is the G4 created by the Global Reporting Initiative. In this context we will focus only on understanding the extent to which the G4 relates to the social and cultural improvements that an economic organization could create during its ordinary administration. Within this framework, the G4 underlines, among its numerous indicators, a series of values that the organization could report.

In order to determine the size of the possible impacts an organization could generate it is extremely important to assess the economic dimensions of the organization: this assessment is made possible by reporting the Direct Economic Value Generated and Distributed, or the Financial Assistance Received from Government.

There is also a dedicated indicator used for the accounting of the indirect impact of the organization’s activity (Global Reporting Initiative, 2013): Significant Indirect Economic Impacts, that includes the extent of said impacts. In the guide to the fulfillment of this indicator, GRI4 reports the examples of the significant identified indirect economic impacts an organization has, both positive and negative. It also includes a list of possible examples such as:

– Changing the productivity of different organizations, fields, or a whole economy

– Economic Development in areas of high poverty

– The economic Impact of improving or deteriorating social or environmental conditions

– Availability of products and services for people with low incomes

– Enhancing skills and knowledge among a professional community or in a geographical region

– Etc…

As one might easily notice, while the main focus is kept on the economic impacts, the guide also suggests and endorses indirect economic impact features like skills or knowledge.

Social Return on Investment

The SROI framework consists of a methodology for measuring and accounting, working towards a broader concept of value; this framework seeks to reduce inequality and environmental degradation and improve wellbeing by incorporating social and environmental costs and benefits.

The SROI methodology (The SROI Network, 2012) is based on seven simple principles:

– Involve Stakeholders

– Understand what is changing

– Value the things that matter

– Only include what is material

– Do not over-claim

– Be transparent

– Verify the results

Following these principles, the SROI guides the organization through a four phases procedure:

The first phase involves stakeholders: the organization is expected to identify, select and engage with the main categories of the stakeholders. This phase should allow to foresee the changes generated by the organization’s activity. Once this phase is over, the analysis moves to the inputs (costs) of the activities. For every category of stakeholder, the possible incurring costs –time cost, resource cost, monetary cost- need to be underlined. In this way, the methodology strives to achieve a good capability of taking into account any kind of input the organization and its stakeholders will produce. In this methodology a central role is played by a list of 2556 indicators, described as “The Global Value Exchange”. This extensive list of indicators, that range from “30 minutes of sport at least once a week (based on the percentage of adults of 16+ years that participates in said activity)” to “Increase in satisfaction within a local area” helps the analyst substantially in measuring the real impact that a cultural initiative generates over time.

In 2007, Impacts Arts used SROI for the evaluation of the North Ayrshire Fab Pad Project, a project that provides vulnerable people with design inputs, creative ideas and practical skills training, designed to help each participant to develop ideas for turning his or her house into a home.

The report identified possible reductions in the recurring homelessness cases of participants to this project, in relation to:

– Reduced Tenancy Support Costs

– Improved Health and well-being of participants and greater family stability

– Reduced Agency Support

– Increased Training and Employment Opportunities

– Movement into the local Labour Market

Overall, the results suggested that for every £1 that had been invested in the project, an SROI of £ 8.38 had been obtained.

However, according to a report given by the LEM Museum (The Learning Museum, 2013), the study was unable to explore some aspects of the creation of value (such as the impact on FAB Pad participants’ families, referral agents and on those who attended sporadically) and did not include the impact on tutors.

This methodology allows researchers to select ex-ante the proper variables needed before presenting the project to stakeholders. Furthermore, one must take into account the usefulness, in defining correctly which impact to measure and why, of the wide list of indicators, among which the researcher could set the project-proxy.

Economic Impact Analysis

Sharing the insights of two previous methodologies with the prevalent Economic Impact Analysis could prove extremely useful. The EIA fund allows to measure the total costs and the total revenue of an organization (for instance, museum tickets and/or touristic expenditure, within the organization’s area). Once the organization calculates this information, it should be able to analyze it following the Input-Output Model.

This model is a quantitative economic technique that calculates the interdependencies between different branches of a national or smaller economy. Following this technique, it is possible for an analyst to estimate how the added value is distributed within the different economic sectors of an area.

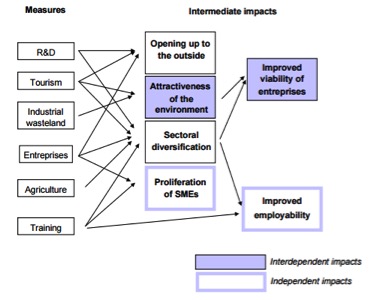

Basically, this model provides analysts with precious insights about how a cultural heritage or event may generate indirect and induced effects on a given territorial area, calculating interdependent or independent impacts.

Source: Evaluating Socio Economic Development, SOURCEBOOK 2,

Digital Ethnography

Alongside to these established methods, in the last years or so, due to the improvement of digital technologies, to the wide-spreading of mobile devices and to the improvement of social networks, a new research methodology has grown more and more relevant in social sciences.

Digital Ethnography, according to the definition given by the ‘Centro Studi di Etnografia Digitale’, is a digital methodology Ethnography Fund, aimed towards the analyzing of the new digital way of life that has been emerging from the culture of the Internet.

The principal focus of this discipline is the audience and the complex network of digital platforms […], which constitutes the natural ecosystem where users interact on the Internet.

As life becomes more and more digitalized and more virtual interactions occur in general everyday experiences, territorial analysis needs to take into increasingly serious account the insights given by this research technique.

In considering the impacts a cultural heritage or a cultural event may have on a given area, digital ethnography could be useful to the analyst in different ways:

1) Representing the flows: by interacting on social networks, people express preferences and values, providing the analyst with self-reported user behaviors. This information could help organizations to estimate the total range of the effects produced on a given category of stakeholders by the cultural heritage or event;

2) Measuring the relative importance of an event, when it is not a mega-event: one of the main difficulties in estimating the impacts of minor events is represented by the relative importance they have in local economies and areas. By comparing the range of influences of the events hosted in a given area and in a given time interval, analysts could formulate hypotheses based on certain parameters.

Although there is still research to be concluded in the evaluation of relationships among cultural heritage, users perceptions, and territorial development, the framework of Digital Ethnography has already produced several interesting research results on territorial issues.

Considering the city as a network, a cultural heritage or a cultural event could be represented as an input in the scheme of this network, making it possible to analyze, using the network analysis’ toolbox, the impacts of this input in the overall framework.

Conclusions

There is no sole standard criteria for the evaluation of the measuring of the economic and social impact produced by a culture on our territories and on our societies. Despite the difficulties, there are several methodologies that could be used to estimate the different kinds of impact. By using these techniques or methodologies in cooperation, a multi-perspective evaluation may be reached by researchers and analysts.

As of today, an impact analysis of such a kind could be carried on by combining:

-GRI 4 principles, in order to evaluate the organization’s impact;

-SROI, to measure the organization’s activities;

-EIA, while analyzing the issues of economic impact;

These methodologies could be also be used jointly with several other disciplines founded on digital methods, such as Digital Ethnography.

Further research is still required in order to evaluate the efficiency of such a joint-analysis, as well as the difficulties that a researcher could be faced with when applying this analysis with an empiric approach.

Bibliografia

Center for Creative Communicty Development. (s.d.). Culture and Revitalization: The Economic Effect of Mass MOCA on its Community.

Coppola, A. (2012). Apocalypse Town. Cronache dalla fine della civiltà urbana. Laterza.

European Union. (s.d.). Green paper – Promoting a European framework for corporate social responsibility.

Global Reporting Initiative. (2013). G4 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. Global Reporting Initiative.

Lazrak, F., Nijkamp, P., Rietveld, P., & Rouwendal, J. (2013). The market value of cultural heritage in urban areas: an application of spatial hedonic pricing. Journal of Geographic System, Springer, 89-114.

The Learning Museum. (2013). Report 3: Measuring Museum Impacts.

The SROI Network. (2012). A guide to Social Return on Investment.

Unesco. (s.d.). Hague Convention for the protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.