Abstract

Despite the ever-increasing attention paid to museums, the storage plays a marginal role: an invisible resource, whose potential is often little explored and/or valued.

What is the situation of archaeological museum storage in Italy?

Some reflections are presented here, rising from the results of a recent statistical survey conducted by the writer during her doctoral research project at the University of Ferrara, in collaboration with the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and with the National Association of Local and Institutional Museums.

Introduction

A museum does not survive if it does not preserve its works. The tools and places essential for preserving the works are the storages (Mottola Molfino 1991).

Unfortunately, despite the ever-increasing attention paid to museums, the storage plays a marginal role: an invisible (or almost invisible) resource for the community, whose potential is often little explored and/or valued.

In Italy, the awareness of the importance of museum collection storage is a relatively recent achievement that has experienced a considerable delay compared to other countries (Fossà 2005).

Recognising the storage – in the same way as the exhibition spaces – a dynamic and multifaceted role linked not only to conservation, but also to research and development (Rémy 1999; Della Monica et al. 2004; Beaujard-Vallet 2011), today constitutes a fundamental challenge for museums, if they want to preserve their role as centres of knowledge at the service of the community.

This challenge becomes even more difficult and problematic for storages of archaeological material, which undergo a continuous and exponential increase (Marini Calvani 2004; Shepherd and Benes 2007; Papadopoulos 2015).

What is the situation of archaeological museum storage? What problems do they face?

In 2014-2015, a statistical survey was conducted by the writer during her doctoral research project at the University of Ferrara, in collaboration with the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and with the National Association of Local and Institutional Museums (Muttillo 2015, 2016, 2017).

The purpose of the survey was to create an updated and comprehensive mapping of the archaeological museum heritage not exhibited, collecting information on the management of goods in storage, mainly on: a) inventory and cataloguing; b) preservation: safety and control of risk parameters; c) structure and organization of storage; d) professional figures involved in the study, care and management of the collections; e) valuation of storage, in terms of accessibility, visibility and use.

Archaeological museums[1], both state and not state[2], have been investigated through a specially designed questionnaire, also available online [3]. The survey has allowed to identify critical elements and priority areas of intervention.

Survey’s results

There are 664 archaeological museums in Italy, of which 113 belong to the State and 551 do not belong to the State (list updated to 2015). The largest number of archaeological museums (state and non-state) is in central (n = 235) and southern (n = 158) Italy. The percentage of state museums is always smaller than that of non-state museums, except for southern Italy. The largest number of archaeological museums (state and non-state) is in central Italy, both in absolute value and in relation to territorial extension and population.

223 museums replied to the questionnaire, of which 61 state museums (54% of the total) and 162 non-state museums (29.4% of the total).

Based on the answers provided by the museums that participated in the statistical survey, these are the priority areas for intervention:

a) Inventory and cataloguing

Museums were asked to provide an estimated percentage (0%; 1-20%; 21-40%; 41-60%; 61-80%; 81%-100%; indeterminate) of the inventoried and catalogued goods in storage with respect to the total amount of stored goods.

Although these are average values, the percentage of inventoried and catalogued goods is very low:

Furthermore, a very low percentage of museums use a digital inventory.

These data appear to be in line with the results produced by the Working Group on Inventory Review coordinated by the Central Institute for Cataloguing and Documentation (Shepherd 2015; Tosti 2015).

The inventory process certifies the existence of a good, with the attribution of a record number, essential identification data, last provenance and economic value. It is the primary and unavoidable step to guarantee the existence, protection and preservation of a good. If a good is not inventoried, technically it does not exist. It does not even exist for the economic patrimony of the State.

Without proper documentation, museums are not able to know exactly what goods they keep in the storage, where they are placed, how they are stored, with obvious complications, even of an economic nature (in case of theft, damage and/or loss).

b) Personnel

The presence of professional personnel exclusively dedicated to the management of the storage is extremely rare in non-state archaeological museums (11%), while it appears more frequently in state museums (58%).

Among the people involved in the care and management of the collections, the archaeologist is the prevailing figure. Restorers, frequent at state museums, are very rare in non-state ones. Other professional figures (such as registrars, cataloguers, technical assistants) are poorly represented.

However, these persons are almost never present at all or they are usually shared among several institutions

The lack of qualified personnel is even more serious if we consider the continuous increase of the museum collections, declared by most of the museums participating in the survey. 70% of state museums and 50% of non-state museums have dynamic collections, which increase with new findings from excavations and rescue archaeology.

c) Valuation and accessibility of storage

The physical and intellectual accessibility of the collections is guaranteed not only through the exhibition of goods, but also by ensuring the consultation of non-exhibited goods.

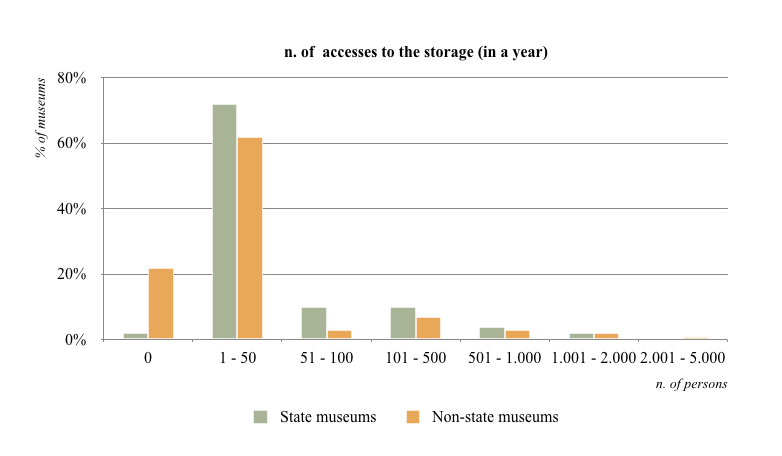

The number of accesses to storage on an annual basis is extremely low, both for state and non-state museums (it rarely exceeds 50 units in a year).

Moreover, at least one institute out of two does not have facilities and equipment to facilitate access for the disabled.

It should also be considered that not all collections of the storage can be viewed, mainly for conservation reasons (particular fragility or perishable state of goods) and safety (custody and surveillance problems), but also for scientific reasons (possibility of view only inventoried, studied and published material).

New technologies offer countless possibilities to ensure accessibility of unexposed materials (online databases, 3D reconstructions, digitised goods available online, etc.). However, at the time of the survey, none of the museums that responded provided the possibility to consult the database online of the stored material.

Therefore, considering the lack of personnel dedicated exclusively to the management of the storage, the limitations to consult the goods, the lack of space for the study/consultation of the goods, we understand how the guarantee of full physical and intellectual accessibility is still far from achieved; as well as the integrated vision of exhibition space and storage, the consideration of the latter as a resource, as a priority.

Conclusions

The statistical survey carried out among state and non-state archaeological museums has allowed to develop an exhaustive and updated mapping of the archaeological museum heritage that is not the subject of exhibition.

While considering the extreme heterogeneity of the Italian museum reality, it is believed that the results, presented briefly here, are not only noteworthy but also acquire particular relevance in consideration of the historical moment in which they are located, picturing the Italian museum situation immediately before the Franceschini reform (d.p.c.m. n. 171 of 29/8/2014).

The statistical survey has revealed that the implementation of the inventory and cataloguing is the priority area of intervention, which is the indispensable step for all other functions and activities linked to protection (even in the case of damage and/or theft), conservation, protection, accessibility, enhancement.

In this sense, it is necessary that the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities issues a prescription to carry out computerised inventory management, which will allow: simplification of documentation; management and traceability processes; rationalisation of resources; reduction of management times and costs; improvement of the quality of the processes; guarantee of widespread access to data and their circulation.

However, it would be appropriate to establish a unitary, unique and shared procedure in order not to repeat the occurrence of the difficulties already experienced for cataloguing.

In this sense, the proposal made by the Working Group on Inventory Review coordinated by the Central Institute for Cataloguing and Documentation is fundamental in modifying the inventoried system used at present with a single inventory management system and financial declaration shared by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (Shepherd 2015).

Considering the difficulties registered also in the cataloguing (Leon and Plances 2009), it would be desirable to further strengthen the collaboration between the various subjects involved in the cataloguing activity, to ensure a univocal information process.

Moreover, it is believed that more attention should be paid to the planning of the aspects related to the storage of material before the excavation. It would also be necessary to better regulate the post excavation, subordinating it to the fulfilment of minimum requirements the authorisation of the excavation concessions.

At the same time, a greater dialogue and cooperation between archaeologists and employees in the care and management of museum collections is desirable to improve the planning of aspects related to the management and organisation of storages.

Last but not least, it is considered necessary to promote greater awareness of the theme of museum storage as a fundamental resource for the entire community, not only for professionals.

In conclusion, the problem of storage is extremely complex and requires a systemic approach, a strategic planning at national level with criteria, methodologies and shared standards.

Unfortunately, the Franceschini reform did not improve the situation as it added further confusion on the assignment of tasks and functions between museums and superintendences.

It is not just a problem of a presumed ‘treasure’ that cannot be enjoyed by the community. It is a political and social problem: it is a loss of cultural and scientific value but also, as we have seen, an economic waste.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all those who have contributed to the planning and realisation of the research project and to all the museums and professionals that have participated in the survey. A special thanks to: Giuseppe Lembo, Roberto Lleras Pérez, Carlo Peretto, Carmela Vaccaro, Elizabeth Jane Shepherd, Jeannette Papadopoulos, Anna Maria Visser.

Footnotes

[1] Archaeological museum: museum with collections of objects, artefacts and materials from excavations or findings, dating back to the late Middle Ages included, bearing witness of ancient civilisations, including non-European ones. Museums of paleo-ethnology, prehistoric and protohistoric archaeology are included.

[2] State-museum: the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities is responsible. Non-state: public subjects other than the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities or private subjects (profit and non profit) are responsible.

[3] http://www.anmli.it/news/indagine-sulla-gestione-dei-depositi-museali-e-sulla-movimentazione-dei-beni-archeologici

References

Beaujard-Vallet, S 2011, “L’évolution du rôle des réserves muséales: les réserves délocalisées du musée de l’Armée”, in La Lettre de l’ocim 138, pp. 11-15.

Della Monica, A, Deloncle, J, May, R, Valaison, MC 2004, “Perpignan, un projet de réserves externalisées et communes. Pour une nouvelle démarche en matière de programmation des collections et de projet de reserves”, in Technè 19, pp. 106-114.

Fossà, B 2005, “I depositi: pianificazione, allestimento e fruizione”, in AM Lega (ed), Gestione e cura delle collezioni, Faenza, pp. 48-51.

Leon, A, Plances, E (eds) 2009, Osservatorio partecipato: le articolazioni del Catalogo nazionale. Rapporto 4, Roma.

Marini Calvani, M 2004, “Dallo scavo al museo e ritorno”, in F Lenzi, A Zifferero (eds), Archeologia del museo. I caratteri originali del museo e la sua documentazione storica fra conservazione e comunicazione, Bologna, pp. 125-129.

Mottola Molfino, A 1991, Il libro dei musei, Allemandi, Torino.

Muttillo, B 2017, Le risorse invisibili. Indagine sulla gestione dei depositi museali e sulla movimentazione dei beni archeologici in Italia, Aracne Editrice, Roma.

Muttillo, B 2016, “Il patrimonio invisibile dei musei. Indagine sulla gestione dei depositi museali archeologici in Italia”, in Forma Urbis XXI 6, pp. 6-9.

Muttillo, B 2015, “Indagine sulla gestione dei depositi museali e sulla movimentazione dei beni archeologici in Italia”, in B Muttillo, M Cangemi, C Peretto (eds), Le risorse invisibili. La gestione del patrimonio archeologico e scientifico tra criticità e innovazione, Atti del convegno (Ferrara 2014), Annali dell’Università di Ferrara di Museologia Scientifica e Naturalistica, pp. 69-72.

Papadopoulos, J 2015, “Movimentazione dei beni archeologici e gestione dei depositi”, in B Muttillo, M Cangemi, C Peretto (eds),, Le risorse invisibili. La gestione del patrimonio archeologico e scientifico tra criticità e innovazione, Atti del convegno (Ferrara 2014), Annali dell’Università di Ferrara di Museologia Scientifica e Naturalistica, pp. 15-24.

Rémy, L 1999, “Les réserves: stockage passif ou pôle de valorisation du patrimoine?”, in La Lettre de l’ocim 65, pp. 27-35.

Shepherd, EJ 2015, “Situazione attuale e nuove proposte per la gestione degli inventari e del valore patrimoniale dei beni archeologici dello Stato”, in B Muttillo, M Cangemi, C Peretto (eds), Le risorse invisibili. La gestione del patrimonio archeologico e scientifico tra criticità e innovazione, Atti del convegno (Ferrara 2014), Annali dell’Università di Ferrara di Museologia Scientifica e Naturalistica, pp. 29-38.

Shepherd, EJ, Benes, E 2007, “Enterprise Application Integration (EAI) e beni culturali: un’esperienza di gestione informatizzata assistita dalla radiofrequenza (RFId)”, in Archeologia e Calcolatori 18, 2007, pp. 293-303.

Tosti, F 2015, “I beni di interesse culturale “invisibili” nel Conto Generale del Patrimonio dello Stato”, in B Muttillo, M Cangemi, C Peretto (eds), Le risorse invisibili. La gestione del patrimonio archeologico e scientifico tra criticità e innovazione, Atti del convegno (Ferrara 2014), Annali dell’Università di Ferrara di Museologia Scientifica e Naturalistica, pp. 25-28.