Abstract

The contribution highlights the main insights of my M.Sc thesis’ research conducted in 2019. It focuses on the widely debated art market issue of the ever more unsustainable costs for the small-medium sized galleries to attend art fairs. Even though their centrality for the galleries’ growth and market affirmation, something has started to change. In fact, the involved actors have denounced an art fairs’ scenario whose participation costs increased at the point for which it became almost impossible to obtain valuable economic results. The situation is exacerbated by the existing booths’ purchasing system. According to this and to the standard art fair’s format with different sections where the galleries are included, the actors in the same section spend the same amount per square meters/feet not considering their effective heterogeneity. Then, they are forced to sustain costs not proportionated to their real economic capacities. Despite the adoption of some progressive measures, the art fairs still seem unable to develop a system reflecting the participants’ diversity. Thus, the research aims to dwell on the art fair business model with a focus on the booths’ purchasing system, hypothesizing the introduction of a pure progressive mechanism for which each one would pay according to what it has. The study has been conducted relying on a review of existing literature about the business model and its application in the Creative and Cultural Sector (CCS). Then, it has been done interviews to 3 selected art fairs’ directors, aimed at reconstructing the art fair business model, and to 4 contemporary art gallerists, evaluating the proposal and discussing the art fairs’ functioning. The directors’ interviews have been done submitting the questions via mail, while the gallerists have been met personally.

The study hopes to lay the foundations for more structured contributions in this field and to stimulate the debate on the way to do business in the art fairs’ environment.

Theoretical Background

The theoretical basis is represented by a comprehensive analysis on the way the business model concept has been defined during a 20-years’ time frame (1998-2018) and its application in the CCS.

Despite of the absence of a universal business model definition, it emerged a shift from the “particular” to the “general”. It relates to the elaboration of more comprehensive definitions since initially the business model was studied in relation to the e-business and technological-related fields. Then, the review highlighted a “convergence process”, both about how to define the business model – ever more as the ratio according to which the value is created, delivered and captured – and in relation to its main constituents – majorly associated with the categories of value creation, value capture and resources.

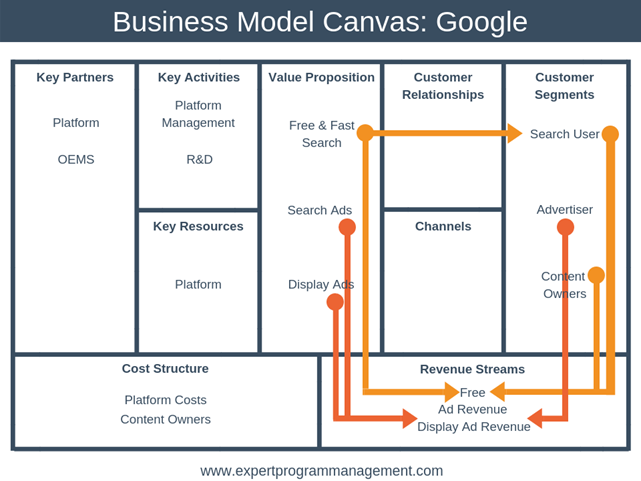

Passing to the business model use in the CCS, the major obstacle was the literature scarcity. However, the Business Model Canvas – a 9 blocks instrument to effectively communicating, representing and describing the ratio of the business model (Osterwalder, Pigneur, 2010) – emerged as a reference tool for the business model management and innovation.

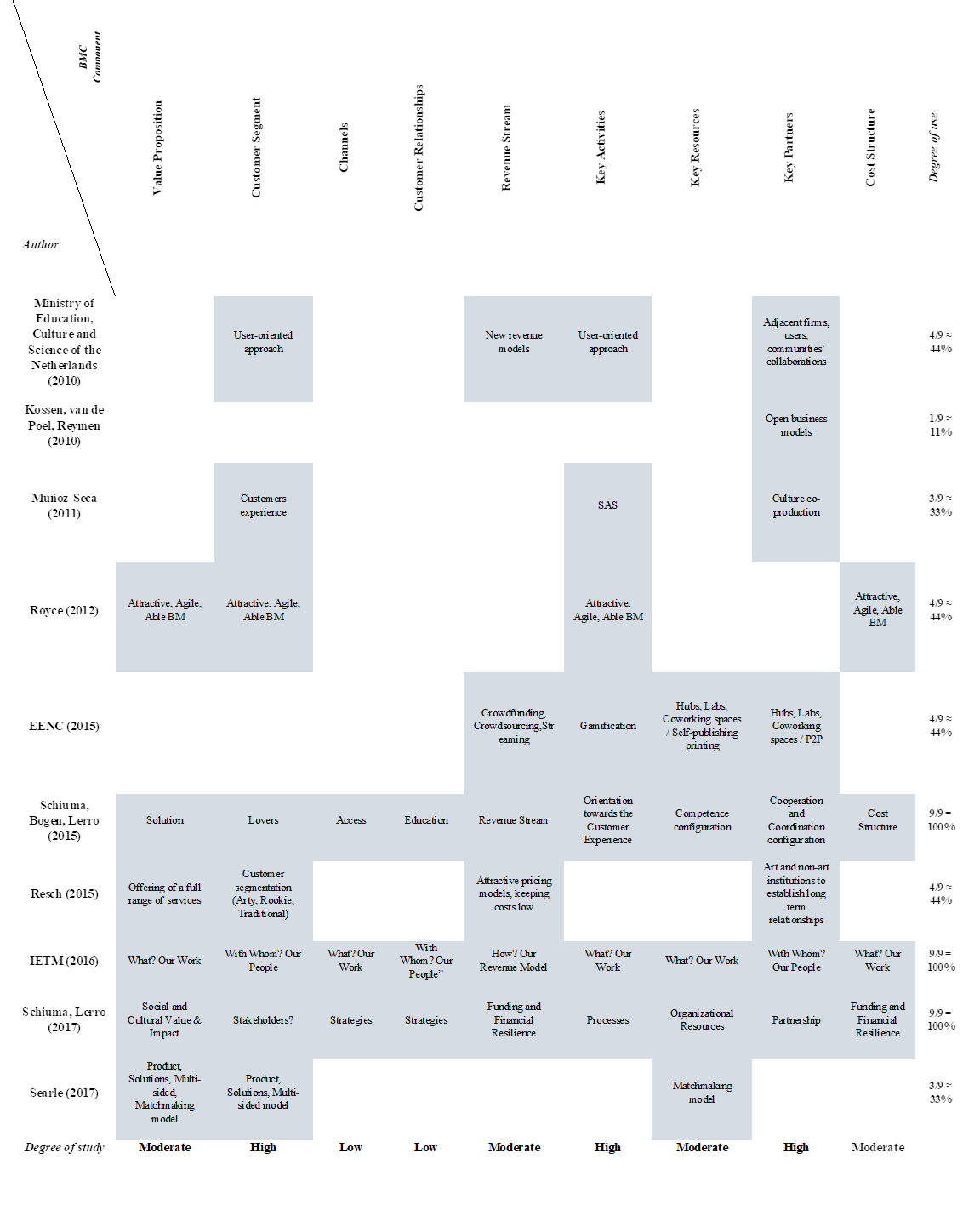

Thus, for each contribution it has been observed the BMC blocks considered and simultaneously the extent to which during a period of almost 10 years each BMC component has been used. It resulted an own elaborated table (see Appendix) for which only 3 contributions (Schiuma, Bogen, Lerro, 2015; IETM, 2016; Schiuma, Lerro, 2017) consider all the 9 blocks. Not for a chance, they are also the cases in which the authors deliberately consider the BMC as a reference tool trying to readapt it for the CCS. Then, while the key activities, key partners and customer segments’ blocks appear as the “most analysed”, curiously the customer relationships and channels do not benefit from the same degree of consideration. It might be because they are specific and different for each case, becoming almost impossible to make generalisations. On this line, the revenue stream component is not central since also in that case it would be difficult to identify generally accepted formula, requiring instead to rely on concrete cases study.

At large, despite the attempts it emerged that the research state of the business model application in the CCS is still in a developing phase.

Methodology

The methodology consists of 4 in person semi-structured interviews with the contemporary art galleries Massimo De Carlo gallery (Milan), P420 gallery (Bologna), 1/9 – unosunove arte contemporanea gallery (Rome) and Clima Gallery (Milan). The ratio was to collect contributions of actors belonging to each of the 3 categories “emergent”, “mid-career” and “established” – generally used during art fairs to label the participants – with the aim to have an overview on how the 3 main market levels evaluate the research proposal. For all the interviewees have been used the same 7 questions format (see the Appendix) but developing the interviews as discussions, leaving them free to introduce additional themes. Then, it has been done 3 structured interviews with the art fairs’ directors of Drawing Room Madrid (Madrid), photo basel (Basel) and paper positions Berlin (Berlin), submitted via mail (see the Appendix). Finally, it has been created an explanatory database collecting information on 50 selected Modern and Contemporary art fairs. It consists of 14 main variables: Fair’s name, Location, Typology of fair, Ticket price, Participant galleries, Number of visitors, Application fee, Booth costs per square meters (both for the Emergent and Established categories), Additional fee, Prizes, Sponsor and Partner (the database results are not part of the article).

Discussion

Unfortunately, only the Drawing Room Madrid director completed the interview format (see Appendix). Consequently, because of the lack of information from the directors (and gallerists) it has been impossible to reconstruct the art fair’s business model, limiting the research extension to widely debate the issues of a progressive payment system and fair’s mechanisms with the selected gallerists.

However, from the Drawing Room director firstly emerged a lack of economic competences to reconstruct the fair’s business model using the BMC, also considering her a humanistic background. Then, she explained how the fair’s pricing policy is conditioned by its small and regional dimension. Given the absence of worldwide participants and a low degree of internationalization, the establishment of the same prices would provide actors with the same success possibilities. Furthermore, she confirmed how they define prices basing on their internal costs to be financially sustainable and to make a moderate profit. Curiously, asking her opinion on the introduction of a pure progressive system and potential alternatives to the fair’s model (“super-partes” authority and galleries’ associations) she did not provide clear answers. Probably, the reticence to talk about similar matters and the limited available time to answer the questions could explain such results. Despite all, the director’s contribution provided with some valuable insights as the scarcity of more diversified and not only arts-related competences in this environment and the necessity to adopt a price policy greatly structured around the fair’s internal costs instead of a logic of simple adaption to the competitors’ actions.

Turning to the galleries’ side, they wanted to keep their names anonymous in the results’ discussions, for which it would have emerged “who said what”. Then, they agreed on using the generic labels “Gallery 1”, “Gallery 2”, “Gallery 3” and “Gallery 4”. According to this, the first gallerist’s main insights refer primarily to the today problem that collectors do not visit the gallery’s space anymore, putting the focus on fairs. What it emerges, is a daunting scenario for the galleries that are forced to attend as many fairs as possible to meet the collectors’ demand, feeding a system for which the gallery’s quality level also depends on the type of attended fairs. Paradoxically, he highlighted how for the galleries is still essential to be part of a similar system – both because economic and networking reasons – for the fairs their attendance is essential to exist, but the conditions established for their participation are simply unsustainable. Like all the other interviewees, he denounced an excessive number of fairs and a consequent “collectors’ dispersion” problem. Then, it became difficult to identify the most convenient fairs to be part of given the doubtful collectors’ presence, increasing the level of uncertainty for the sales’ results but having to sustain sure high costs. On this line, he both stressed the importance to prioritise the fair’s economic dimension to make it more sustainable instead of its mundane dynamics and to recover an economy putting at the centre the galleries, with art fairs as supporting actors. Today this logic is subverted. Collectors do not experience anymore the gallery space considering instead fairs as unmissable occasions to continuously find new artists and proposals. Going on, he completely agreed on the introduction of a progressive system but excluding the proposed idea to rely on the galleries’ profit, citing instead the number of years the gallery has attended the fairs, its years of activities and the prices of the exhibited works. Then, he rejected the idea of a “super-partes” authority because of the impossibility to create a unique regulation able to adapt everywhere. Instead, he proposed the creation of galleries’ associations with contractual power allowing them to negotiate more favourable conditions with the fair.

The Gallery 2 highlighted a really different perspective also because of its higher market dimension. Firstly, he stressed the fairs’ essentiality referring to the already cited economic and networking reasons and claiming that their high number is simply a reflection of the businesses’ profitability. On this line, he sustained the importance for the participants to be “prepared” in the sense of studying the market, gathering information on attendants and consequently on the type of artists who should be exhibited, getting off the perspective for which it is enough to simply “be present” hoping that someone will buy something. Consequently, he rejected the cited “collectors’ dispersion” problem since everyone working in the field knows “who goes where”. Thus, he also showed a different view of the progressive payment system. In fact, despite its theoretical rightness is affected by the intrinsic problem of lack of transparency. Regardless of all the potential reference variables, everyone would be incentivized to provide underestimated information to pay less even considering the impossibility to check information truth. Nevertheless, he believed that the profit level, number of human resources employed, artworks’ prices and patrimonial data could be used in theory for the definition of a sort of algorithm aimed at helping the payment of more proportionated costs, but still having in mind the transparency obstacle. More in general, he came up with a more positive view on art fairs’ and on their configuration as mundane events. Their ability to provide a diversified offer is not only essential to define competitive advantages and survive in the market but also contributes to increase their appeal for curators, collectors etc helping galleries to obtain better results. So, for him the commercial and mundane fairs’ spheres are today inseparable and essential. Considering the other proposals, he rejected the “super-partes” authority idea (same reasons of Gallery 1) and strongly doubted of the galleries’ ability to create negotiating associations given the impossibility to define common interests. Then, he concluded with some ideas to improve art fairs. Firstly, the importance of a VAT percentage and import tax reduction during the event to create more favourable conditions for the dealers. Then, the opportunity of smaller high-quality galleries to attend for free the fair and a change in the gallery-director dialogue. It should be created a constant and “personal” dialogue with the participants, proposing them “what to do” in terms of the most convenient gallery’s offerings for the fair, basing on their cultural proposals, target prices and sales potentiality. So, each gallery would be provided with a tailored strategy increasing the probability to obtain satisfactory results.

The Gallery 3 has much in common with the first one, not for a chance moving on a similar market dimension. In fact, he underlined the excessive fairs’ numbers and the “collectors’ dispersion” problem, adding that while major fairs have unsustainable costs, the newer ones are a “bet”. Despite their low costs they lack affirmation in the market reducing the chances to make positive results. On the other hand, today even major events do not grant galleries with satisfactory outcomes, stressing how it does not exist a right formula with which select fairs. Turning to the progressive system, he reputed it theoretically correct but difficult to be implemented since the reticence to provide data (as the profit) and the uncertainty about how effectively implement the potential variables (human resources, patrimonial data and exhibited artworks’ prices). Then, despite the rejection of the “super-partes” authority idea, he proposed an improvement of the associative tendency. On this line, galleries should create an own Chamber of Commerce aimed at managing their sensitive data in a way to both negotiating and participating with the fair entity to the budget formation (that today exclude the galleries’ participation). Finally, he agreed on the art fairs’ mundane side at the condition that would not excessively “distract” art world professionals with collateral events.

The Gallery 4 reflects a view more in line with the second interviewee. Firstly, he stressed how the huge fairs’ number represents the market response to the positive increase of the art-related demand. Then, he did not only refer to the positive economic and networking gains but also to a different view of the “collectors’ dispersion” issue. He explained a logic of “finding” and “losing” for which it is true that collectors spend the greatest part of their time attending fairs worldwide, but the possibility to attend such events automatically grant the gallery to access to the wide pool of the other actors’ collectors, in a logic for which what it is found almost always compensate what it is lost. Going on, he labelled the progressivity theme as dangerous and unfair. According to him, it is simply not equal that stronger actors would pay more since they have also been “small” in the past, risking generating discontent and inducing them to stop attending events that have potentially adopted this mechanism. Moreover, he marked the impossibility to find completely objective criteria on which structuring the progressive system. This is because of the incentives to lie in a way to pay less and the impossibility to check the truth of the given information. Turning to the alternatives, he both rejected the “super-partes” authority idea and the associative one. For him, the hypothetical association would not be able to attract enough galleries to rise a real contractual power with the fair not to mention the impossibility to define common objectives. Thus, viable solutions would be to improve the conditions already provided by art fairs (e.g. access to the “emergent” section if the gallery is in business for less than 8 years instead of 5) and to make more accessible their additional services (e.g. lighting/whitening services). The selected companies should establish market prices, allowing all participants to create appealing booths being then more competitive.

Conclusion

Summarizing the main research outcomes, it emerged a convergence process of the business model conceptualisation, from field-dependent to more comprehensive definitions, and a still-developing phase about its understanding through the BMC in the CCS.

Then, the art fairs’ scenario appeared as an “opaque” environment due to the lack of directors’ contributions and gallerists’ approximate knowledge. Instead, they showed different perspectives on the progressive payment system. The “smaller” actors highlighted a more optimistic view and stronger exigences about its adoption while the “bigger” ones stressed more its impracticability and partial unfairness. In that sense, they came up with interesting and provocative potential alternatives as the creation of galleries’ association with contractual power, structured gallery-directors’ dialogue, negotiations between fairs and governments (VAT, import tax), higher inclusion for free of smaller but high-quality galleries, creation of a galleries’ Chamber of Commerce, and general improvement of already existing fairs’ conditions. All of that, with a common rejection of the “super-partes” authority proposals. As regards the today fairs configuration as “events”, almost all the gallerists (3 out 4) were favourable on recognizing its essentiality for the fair’s market survival.

Finally, the results have to be interpreted considering the impossibility to reconstruct the art fair’s business model because of the lack of directors’ contributions and of quantitative analysis. Then, future studies could focus on the quantitative dimension using that study as a basis and involving more art fairs’ workers and art world professionals given the significant contributions and proposals obtained from a limited number of interviews.

Bibliography

MSc final thesis “The art fairs business model and a progressive price system: an empirical analysis” (Gabriele Medaglini, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, 2019).

Appendix

Contemporary Art Galleries’ Interview format (Italian version)

L’obiettivo della ricerca è ottenere una panoramica – il più dettagliata possibile – sul modello di business dell’ente fieristico, tramite interviste a diversi direttori di fiere d’arte internazionali e galleristi. Da qui, prendere dunque in considerazione l’idea di introdurre un sistema di pagamento progressivo per le gallerie partecipanti riguardo l’acquisto dei loro spazi di stand. Ad oggi infatti, le gallerie nella medesima sezione – come ad esempio “established” – pagano la stessa cifra per m^2, delineando una situazione per cui sia un’ipotetica galleria di dimensione mondiale che una più piccola (che forse è stata appena promossa in quella stessa sezione) sostengono lo stesso prezzo. L’idea dunque, è quella di sviluppare sistema di prezzo puramente progressivo, tramite il quale ogni galleria partecipante possa sostenere costi in base alla sua reale “capacità” (fatturato, numero di sedi, valore delle opere esposte e così via).

1. Parere sulla situazione attuale delle fiere d’arte (troppe/troppo poche, se sono ancora così fondamentali, se il loro meccanismo favorisce di fatto tutte le categorie di attori coinvolti);

2.Quanto l’attuale politica di prezzaggio grava sulla vostra partecipazione? In generale, dato il gran numero di fiere e gli elevati costi, ritiene che per continuare il processo di crescita (soprattutto per attori “medio-piccoli”) sia meglio incrementare la partecipazione a fiere meno blasonate e meno dispendiose o continuare comunque ad affrontare costi significativi ma essendo inseriti in un contesto più “rinomato” (con tutti i benefici del caso: network, collezionisti…);

3.Parere circa l’introduzione di un sistema di pagamento progressivo;

4.In teoria l’ammontare pagato dipenderebbe da variabili quantitative, prime fra tutte fatturato e numero di sedi. Sareste disponibili a fornire dati di questo tipo ad un ente privato come la fiera?

5.Commento finale su idea di introduzione di un sistema di pagamento progressivo per le fiere (percorribile o meno, corretto/non corretto ecc…). Quali potrebbero essere gli attori da coinvolgere per muoversi in questa direzione? A tal proposito come valuta l’idea di creare un’associazione di gallerie le cui quote associative sarebbero direttamente devolute al supporto degli attori più “piccoli” durante gli eventi fieristici (piccoli in base a parametri quali fatturato, numero di sedi e così via)? Oppure, come valuta l’idea di introdurre un organismo “super-partes” tale da stabilire un’univoca politica di prezzo e regolamentazione delle fiere a cui i vari enti debbano attenersi (invece che continuare a lasciare totale autonomia agli enti privati)?

6.Cercando di immedesimarsi nella prospettiva di un direttore di fiera e considerando come base le componenti del business model canvas *, riuscirebbe a compilarne le varie sezioni, risalendo così alla loro struttura interna? Oppure, quali sarebbero a suo dire le dimensioni principali su cui lavorare per facilitare una partecipazione più equa (e potenzialmente l’introduzione di un sistema di pagamento progressivo)?

7.Ulteriori considerazioni su cosa ad oggi le fiere d’arte possano migliorare per venire incontro alle esigenze delle gallerie partecipanti.

* Business Model Canvas: framework impiegato per la rappresentazione e descrizione del business model dell’attività. Componenti:

– Value Proposition: è il valore che si crea in virtù del soddisfacimento di un bisogno o risoluzione di un problema (non è il semplice prodotto/servizio);

– Customer Segments: il target di clienti a cui ci si rivolge;

– Channels: come il prodotto/servizio viene distribuito;

– Customer Relationship: le strategie con cui si punta ad incrementare il numero di clienti, con cui si mantengono quelli già esistenti, e con cui si cerca di aumentare il loro consumo del servizio/prodotto;

– Revenue Streams: composto da revenue model (strategia con cui si ottiene cash dai clienti – ad esempio “asset sale”: l’ammontare ottenuto deriva dalla vendita del bene/servizio, “subscription fee”: pagamento di un ammontare fisso da cui deriva la fruizione di un bene/servizio) e definizione della politica di prezzo (principalmente in base ai costi sostenuti o al comportamento della concorrenza):

– Key Resources: risorse necessarie per lo sviluppo del business;

– Key Activities: attività principali per il business;

– Key Partners: se per lo sviluppo del business è necessario stabilire relazioni con partner esterni;

– Costs Structure: tutti i costi da sostenere.

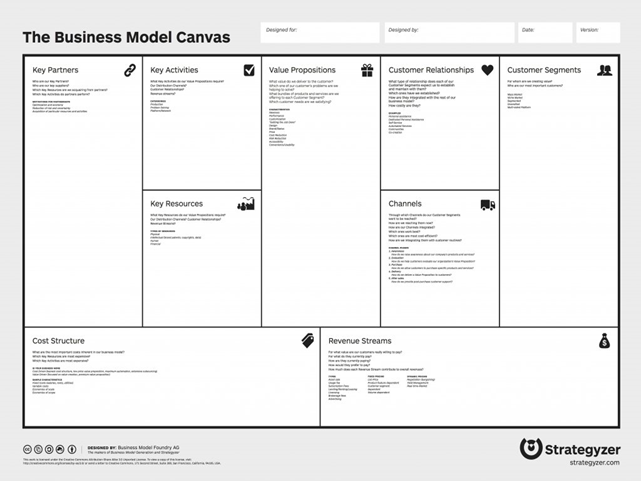

The framework:

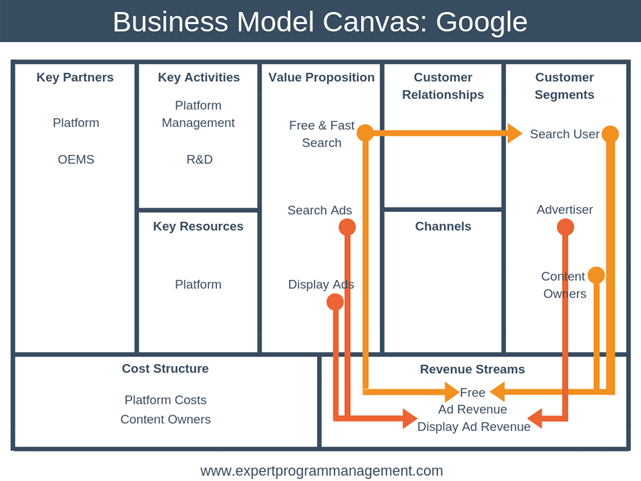

Example of Business Model Canvas:

Art Fairs Directors’ Interview formats (English version)

The research purpose is to have an overview – as detailed as possible – about the structure of the art fair’s business model relying on interviews to a selected pool of fairs’ directors and gallerists to reconstruct its business model. Then, making considerations about the idea of introducing a progressive payment system for the galleries as concerns the purchasing of their booths’ spaces. Nowadays in fact, the galleries in the same section, as for example “established” one, pay the same amount per square meter. So, both a hypothetical worldwide gallery and a smaller one (that maybe has just been promoted in that section) sustain the same stand fee. My idea in that sense is to evaluate the possible introduction of a purely progressive mechanism, for which each actor could sustain costs according to its real capacity (so basing on their level of profit, number of venues, price of the artworks exposed and so on).

1.Description of the fair’s governance model. Is it a private entity with its own right commissions? Or, is there a broader institution aimed to support/manage the overall activities (as the case of MilanoFiera with miart contemporary art fair in Milan)? If yes, what is it doing specifically?;

2.Your opinion about the idea of a progressive price system (in relation to the stand costs);

3.Considering the Business Model Canvas instrument *, would you be able to fill the relative blocks, reconstructing the art fair business model?

4.Basing on what has been said about the components of the canvas, is it possible to identify some main blocks on which intervene in a “savings” perspective, allowing a reduction of the participation costs of for the galleries (or potentially facilitating the introduction of a progressive payment system)?

5.How much does the pricing policy adopted by the other fair organizations affect? The prices definition in Photo Basel is mainly based on its “internal” scenario or is there a simple alignment to the behavior of the other fair entities?

6.A final comment on the idea of introducing a progressive payment system for fairs (possible or not, correct/incorrect etc …). What could be the actors that should be involved to move in this direction? In this regard, how do you assess the idea of creating an association of galleries whose membership fees would be directly used to support the “smallest” actors during trade fair events (an actor would be defined as “small” mainly based on its turnover and number of venues)? Or how do you assess the idea of introducing a “super-partes” organization to establish an unambiguous price and regulation policy of the fairs to which the various institutions must adhere? (instead of continuing to give total autonomy to private entities).

7.Final considerations on what art fairs can nowadays improve to ever more meet the needs of the participant actors.

* Business Model Canvas: framework used for the representation and description of the entity’s business model. It is composed of 9 main blocks:

– Value Proposition: it is the “value” that is created through the satisfaction of a need or resolution of a problem (it is not the simple product/service delivered);

– Customer Segments: the customers targeted;

– Channels: how the product/service is distributed;

– Customer Relationship: the strategies aimed to increase the number of customers, but also with which keep and grow the already existing ones (growing means to increase the level of their current level of service/product consumption);

– Revenue Streams: consists of the revenue model (the strategy with which you get cash from customers) and definition of price policy (mainly based on costs or on what the competitors do);

– Key Resources: resources needed for the development of the overall business;

– Key Activities: main business activities;

– Key Partners: if for the business development it is necessary to establish relationships with external partners;

– Costs Structure: the overall costs that have to be sustained for business development.

The framework:

Example of Business Model Canvas: