Introduction

Urban development has long been an issue beyond the scope of European policies, and therefore rested in the domain of the individual member states. However in the definition of territorial development principles and objectives for the EU territory as a whole, for which the 1999 European Spatial Development Perspective and the 2007/2011 Territorial Agenda of the European Union are the decisive documents, a crucial importance has been attributed to the European cities and their regions. The globalisation process, which has led to a profound restructuring of socioeconomic, cultural and spatial relations, may be “conceptualised as a multi-layered process of expanding and intensifying transnational networking” (Krätke et al., 2012: 2), and it is urban regions that are seen to constitute the nodes, in which the transnational flows e.g. of people, capital, and knowledge intersect as they provide the service functions necessary for the control and coordination of world-wide linkages (Kujath, 2002; Hall, 2004; Parysek, 2007; Sm?tkowski & Gorzelak, 2008).

In accordance to both the principle of achieving territorial cohesion, and to the objective of improving global competitiveness of the EU on the basis of a knowledge-intensive economy, the strengthening of urban regions is seen as a key policy. Concerning the aspect of territorial cohesion, the target is to create especially outside the “EU Pentagon” a couple of dynamic centres that become well-integrated into the global economy, and thus contribute to the development of their respective part of Europe. As stated in the 2007 Leipzig Charter defining essential recommendations for the development of European cities, through the application of integrated development policies European cities and their regions are to be turned into “centres of knowledge and sources of growth and innovation” by exploiting their “unique cultural and architectural qualities, strong forces of social inclusion and exceptional possibilities for economic development” (Leipzig Charter 2007: 1).

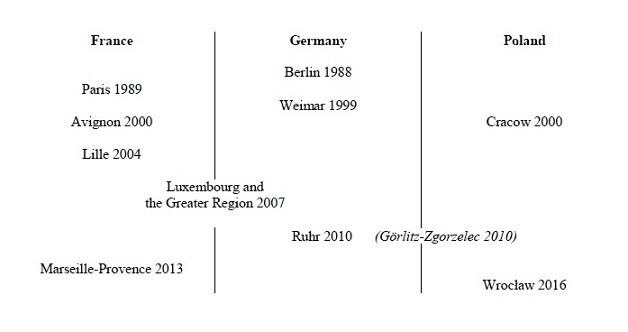

This article will look at the aspect of how this shift from urban to integrated urban-regional development policies is expressed by the example of the European Capital of Culture (ECOC) venture. In the outlined context, this former seasonal city festival to promote the variety as well as the shared values of European culture has in fact evolved into an example for “a kind of European urban policy by different means” (Habit 2011: 154). The ECOC event helps to build cooperation structures across administrative and administration boundaries, requests the definition of a place identity – and of a city image deriving from that – in the sense of strategic marketing, assists in specialisation and cluster building policies notably in the fields of creative and culture industries, and contributes to a heightened attractiveness based on culture infrastructure and heritage. As all of these aspects have become issues surpassing the boundaries of cities, the ECOC has in consequence taken a “regional turn”. This turn from a cultural event to an urban regeneration engine, and then to a policy tool for urban-regional development by culture, will be discussed by the example of the French, German and Polish ECOCs (fig. 1). A final impetus is to lie on the question on how far this turn is reflected in the case of the Central Eastern European cities.

Fig. 1: The ECOCs involving French, German and Polish cities

Source: own compilation

ECOC as a seasonal city culture festival

The idea to establish a “European City of Culture” was born in an attempt by the then twelve European Community member states to create a counterbalance to the overwhelming economic character of joint policies. Culture was seen as a mean to bring the people of Europe closer to each other and to raise acceptance for the European integration project. So starting in 1985 with Athens, the European Commission denominated annually “an individual city, enabling it to act as a focus for artist activity, and a showcase of cultural excellence and innovation” (Griffiths, 2006: 417). The cities – to be chosen in an intergovernmental selection process – were to represent the common elements of European culture, and at the same time its variety and rich diversity. In consequence national governments chose to propose cities with a broad culture life of European standing, such as Florence in 1986 and Amsterdam in 1987.

Berlin 1988

This was followed by the nomination of divided Berlin – in practice of course only of its Western half (where 2 of the then 3.1 million city inhabitants lived) – for 1988 by the West German federal government. So again a national culture hub had been selected, yet at the same time the choice was a political statement to demonstrate that Berlin – despite its marginal geopolitical location – was well a city in the middle of Europe, and a place well able to demonstrate “the identity of European culture across nations and blocks” (Hassemer, 1988: 515). So there may have been some geopolitical macro-regional aspect to this ECOC in wording, however the event itself was seen as a bit of a “chill-out” after the pompous celebrations of the 750th city anniversary in 1987 which actually had been combined with the implementations of a large number of architectural and urban projects (among them the final presentation of the International Building Exhibition). In consequence Berlin 1988 had the character of a cultural festival whose programme left hardly any marks on the socioeconomic and physical development of the divided city.

Paris 1989

The French capital city, with its then about 2.2 million inhabitants in an agglomeration with more than 9 million, stands arguably for the most neglected of all ECOC events – sometimes swiftly described by the words “no programme, no budget” (Oerters, 2008: 98). The municipality of Paris concentrated on organising the national celebrations of the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution in 1989 by numerous large-scale events, and it did not quite embrace the idea of organising at the same time a ECOC programme. The underlying problem was that the nomination as European City of Culture 1989 had been promoted by the national government on the European level without much prior consultation with the city’s authorities, anticipating that the event would be an enrichment to the national celebrations. As a result the city of Paris treated the title rather as an award honouring its cultural importance (ibid.), and organised only a small low-budget cultural programme without any long-term effects.

ECOC as an urban tourist, image and regeneration project

The low-key event in Paris was to be followed by the ECOC that is widely seen to have profoundly changed the character of this venture in the long run: Glasgow 1990. Other than all of its predecessors this city had a reputation rather based on industrial decline and social problems than on culture, so as Booth & Doyle (1994: 32) put it “the title of ‘European City of Culture’ was in Glasgow’s case bringing the status rather than the status of the city bringing the title.” Glasgow became a symbol of how a de-industrialising city may implement a campaign based on culture to reinvent itself, to change its image and start a restructuring process. And consequently Glasgow gave a new meaning to the ECOC event: it started to be seen as a restructuring engine creating economic benefits deriving from increased tourism figures, boom of the culture industries, image enhancement and urban regeneration. Nevertheless most ECOCs of the 1990s still were big national culture hubs (Dublin, Madrid, Lisbon, Luxembourg, Copenhagen, Stockholm), while Antwerp 1993 and Thessaloniki 1997 were somewhat following in the steps of Glasgow in that both cities – characterised by a decline in industry and port activities – were struggling to revive their local economy and to regenerate their cityscape. There was however one main objective uniting all ECOC in that period: to improve the image of the respective city, to strengthen its culture infrastructure, and to enhance its capacity to attract tourists, notably in the context of a quickly expanding city trip market (Evans, 2001; Mittag & Oerters, 2009). It is in this context that the respective second French and German ECOC, and the first Polish one, are to be seen.

Weimar 1999

The locally-born idea of making Weimar the first ECOC East of the former Iron Curtain was quickly embraced by the German federal government. 1999 was not a coincidentally chosen date, as it marked the 250th birthday of Goethe, the 240th birthday of Schiller (with the life of both of them being closely related to Weimar), the 80th anniversary of the Bauhaus school (founded in Weimar) as well as of the proclamation of the Weimar Constitution (Germany’s first democratic constitution), the 50th anniversary of the proclamation of the Federal Republic of Germany, and the 10th anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall. So the tiny city of Weimar with its 65,000 inhabitants is undoubtedly a cultural hub of European standing and “synonymous with the remembered unity of German and European culture” (Keohane, 1999: 40), yet with the site of the Buchenwald concentration camp it stands also for Nazi barbarism. In addition, it is a city that figures twice on the UNESCO World Heritage list with its Bauhaus as well as Classical Weimar ensembles. The huge financial impact was used to renovate the numerous historic cultural heritage sites and museums in Weimar that had suffered under socialist lack of investment for decades, and to refurbish the whole cityscape, its housing fabric and public spaces. Because of its limited size, Weimar is perhaps the only example where the European Capital of Culture title has indeed led to an upgrading of nearly the whole city. It became “a nice looking city, a little ‘Disneyworld’ faking its own images and staging its own narratives” (Hassenpflug, 2004: 22), yet this focus on the “myths of Weimar” (ibid.) itself meant that there was very limited – if any – impact on a regional scale, and even in the close-by cities of Erfurt, the capital city of Thuringia, and of Jena (each some 20 km away) the event was not making much difference.

Avignon 2000

The turn of the millennium marked the modification of the procedures to select a ECOC. In 1995 the European Union had enlarged to 15 members, and another 12 countries were waiting to join the EU. In consequence the list of potential ECOCs grew longer as the prestige and socioeconomic effects of this event had made it attractive both for city municipalities and their national governments, which rivalled to get a designated year for their candidate city. After lengthy negotiations the European Commission and the European Parliament agreed in 1999 on turning the ECOC (now uniformly named European Capital of Culture) from an intergovernmental to a Community action, and to define formal procedures for the selection process (Mittag & Oerters, 2009). As a result the decision was taken to assign from 2005 on one year for each country for which it could propose a ECOC to the European Commission. And there was the option to have more than one ECOC in one particular year, which from 2009 would become consequently used to select one city from an old and one from a new (accession in 2004 or later) EU member state. These new procedures had somewhat be preceded by the earlier decision of the European Commission to grant the ECOC title in the symbolic year of 2000 to no less than nine cities all over Europe, including two in the then EU candidate countries and two in non-EU countries. This decision was meant to pay tribute in the millennium year to the European cities’ role in culture and civilisation, yet it also was undoubtedly an effective mean to shorten the long list of ECOC candidate cities. Among the cities selected was the second French ECOC, the city of Avignon. The municipality of this comparatively small city with some 85,000 inhabitants aimed at integrating “its already strong position as a tourist destination with the ‘European’ dimension of the City of Culture initiative” (Ingram, 2010: 17). In consequence Avignon 2000 is another example of a city using its existing large cultural potential – in this case based on the outstanding cultural heritage as medieval “City of Popes” and on the annual Avignon Theatre Festival of European renown – to stage a year-long cultural festival that boosts tourism figures, has a lasting image effect, and is a catalyst for the upgrading and refurbishment of the cultural and tourist infrastructure (including the building of a new arts museum), as well as of the public space. So Avignon 2000 had the “top priority” of raising the city’s international profile (Sacco & Blessi, 2007: 128) and left a clear mark in the cities’ fabrics and infrastructure, it had however few synergy effects for neighbouring communes and the region.

Cracow 2000

The city of Cracow with some 750,000 inhabitants is the historic capital of Poland and arguably the country’s most important cultural centre, with its vast Old Town together with the Wawel castle being a UNESCO World Heritage site. In the early 1990s a local initiative lobbied for making the city the first Polish ECOC, and the idea was embraced and finally successfully lobbied on the European level by the Polish government. So Cracow was to become one of the nine ECOC in 2000, and – together with the Czech capital of Prague – one of the first in an East Central European country. Cracow 2000 was to become the highlight of a five-year-long culture festival inaugurated in 1996 on different themes, which was accompanied by a nationwide as well as international marketing campaign. While the cultural activities were quite impressive the event was hardly linked to any investment in cultural infrastructure or heritage, which actually constituted a main point of complain by local culture and tourist managers (Hughes et al., 2003). However the event achieved the objective of turning around the negative trend in tourist figures in the 1990s, and it is felt that it “helped in the international promotion of Cracow” (Gierat-Biero?, 2009: 85) in that it had its share in the steep development of the city into a major tourist destination after 2000. One has to conclude however that an effect concerning the mastering of the post-socialist transformation process – be it the regeneration of run-down urban fabrics, or the restructuring of the local economy – had neither been achieved, nor even been defined as objective. There was also no regional aspect involved, not least because voivodeships as regional self-government units were not created in Poland before 1999.

ECOC as a regional restructuring project

The first decade of the new millennium saw a broad variety of ECOC types. On the one-hand side there was a tendency towards smaller cities constituting rather regional than national culture centres, and trying to use the event to boost tourist figures and to make themselves better known internationally. On the other hand side there was an increase of de-industrialising large urban centres that wanted the ECOC event in order to strengthen or to kick-off a restructuring and regeneration process, so of cities following the footsteps of Glasgow 1990. And as a result of the 1999 reform of procedures to nominate a ECOC, the selection process has been in effect shifted to the national level. So particularly in larger member states selection procedures were created, replacing to some extend the practice of sheer informal and “behind-closed-doors” lobbing. In addition, in 2006 the European Commission published a “Guide for cities applying for the title of European Capital of Culture” defining for the first time the expectations of the EU concerning a ECOC. The choice of Liverpool 2008 may be seen as the first example of an open contest in structures defined by the national government, including pre-selection and short-list procedures (Griffith ,2006). This included the necessity for interested candidate cities to prepare sophisticated concepts on how they would organise the event, including organisational and financial structures, guiding motives and themes, integrated public and private partner institution, envisaged urban projects, prepared festivals and happenings, etc. (Tölle, 2013). All this may have been included in ECOC concepts before, yet by now such detailed concepts were to be prepared by a large number of candidates – of which of course in the end only one would win and actually stage the event. In consequence ECOC bits are being prepared most thoroughly by those municipalities that expect the highest impact on their city’s development, and by those that will use the main aspects of the candidate concept – perhaps in a reduced form – as corner points for their development policy anyway. Hence the ECOC has become closely linked to the field of urban development according to emerging EU concepts, which explains why the venture – just like the task of city development in general – has started to expand into city regions. And as the preparation of a candidature requires networking right from an early stage, it is a logic consequence that the network of partners supporting the bit may be extended beyond city boundaries. It is in this context that the ECOC has started to take a regional turn.

Lille 2004

The overall idea of Lille 2004 was to support the transformation from a declining industrial city at the periphery of France towards an international service as well as culture and innovation hub in the heart of Europe. Lille 2004 is seen as perhaps “the most European” (Sacco & Blessi, 2007: 132) of all Capitals of Culture, as networking for this event included indeed promoting the city – lying at the crossroads of the Eurostar lines to Paris, London and Brussels – as an attractive location for international headquarters and firms, as well as presenting it as a cross-border metropolis. This policy for a declining textile industry city had been started in the 1990 and included a strategy of socioeconomic restructuring by urban projects for the whole agglomeration, whose flagship was the erection of the new high-speed train station “Lille Europe” that had been combined with a large-scale urban brown-field site project, i.e. the building of a new business district under the name of Euralille. The driving force of this process was the “Urban Community of Lille Métropole”. Lille Métropole unites 85 communes with 1.1 million inhabitants (of which 230,000 live in the city of Lille), however it is but the central part of a larger conurbation with common structural problems that extends well across the urban community’s boundaries. In addition, this conurbation has a cross-border character as it includes communes in Belgium, which had led to a tradition of regional cross-border cooperation (Letniowska-Swiat, 2002). In consequence the ECOC event was extended to the whole wider metropolitan region around the city of Lille, i.e. to 193 cities and towns, some of them in Belgium: “The event was conceived from the start as a cross-border event, with the Flemish and Walloon neighbours of Kortrijk and Tournai, but also in a regional dimension, at the scale of the whole Nord-Pas-de-Calais.” (Paris & Baert, 2011: 35).

This was reflected by the representatives in “Lille Horizon 2004”, the association managing the event, as well as by the contributors to the ECOC’s budget – both including local and regional partners from the French and the Belgian side. The event was certainly one of the steps towards the creation of the “Eurométropole Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai” cross-border district with two million inhabitants in 2008, which at that time was the first European Grouping for Territorial Cooperation to be created in the EU (ibid.). Lille 2004 was clearly inscribed into the policy of restructuring an urban conurbation by urban projects (including the building of two new cultural facilities, conversion of post-industrial buildings into social and cultural centres, renovation of cultural facilities and heritage objects), of strengthening the base for culture and creative industries, of raising tourist figures, and of supporting the socio-cultural basis for building a cooperating cross-border metropolitan area (Sacco & Blessi, 2007; Paris & Baert, 2011). Thus it may be concluded that just as Glasgow 1990 had shown the potential to use the ECOC event to support a culture-led regeneration and restructuring process of a de-industrialising city, Lille 2004 demonstrated that this may be extended to the scale of a metropolitan region.

Luxemburg and the Greater Region 2007

The city of Luxemburg with about 100,000 inhabitants had been European City of Culture in 1995, and had used the event for massive investment in the building of an extended cultural infrastructure. This formed the basis for the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg being the centre point (and the coordinator) of the 2007 European Capital of Culture event that actually comprised the cross-border territory of the Greater Region (Großregion/Grande Région with more than 11 million inhabitants). This is the Luxembourgian-German-French-Belgian transnational cooperation space widely seen as constituting a role model for the European integration process, as here numerous multi-level cross-border cooperation structures built since the 1970s have resulted in the creation of a cross-border region with own institutions and defined cooperation fields. Hence organising the ECOC venture – awarded for the first time to a region – meant the implementation of a flagship project of cultural integration: “The Greater Region, laboratory of Europe” was the federal leitmotiv of Luxembourg 2007 (‘Luxemburg and …’, 2008: 20). Each of the five regions involved (i.e. Luxembourg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saarland, Lorraine, and Wallonia) was responsible for one cultural topic, which was reflected in the organisation structure of the event. There were two associations called “Luxemburg and Greater Region, Capital of Culture 2007”: one comprising of government and institution representatives from the Grand Duchy and its capital city, and a second one – with the annex of “Cross-Border Structure” to its name – with representatives from the Grand Duchy and the four regions in Belgium, France and Germany. Accordingly, the general coordination of the programme was executed by an institution in Luxemburg, yet there were also five regional coordinators installed. Of the top twenty culture events (according to numbers of visitors), seven took place in one of the German regions and six in French Lorraine, while five in Luxemburg and two across the Greater Region (ibid.: 33).

A clear marketing and communications objective was to “construct a new regional identity, and reinforce the cultural identity of the region” (ibid.: 55). And from a regional management and marketing perspective, the ECOC event was to have a lasting effect indeed, as its cross-border structures were afterwards used to create the “Espace culturel Grande Région”, i.e. an institutionalised form to continue working on the creation of a regional cultural identity for the Greater Region. It also contributed to reinforce the position of Luxemburg as a cultural pole in that region (Sohn, 2009). However the shire size of the Greater Region territory, seen in relation to budget volumes and the objective of attributing a central role to Luxemburg, combined with insufficient financial engagement of the regions and the political barriers inevitable in cross-border projects, led to the result of an uneven distribution of lasting effects between Luxemburg itself and the Greater Region. So it is fair to conclude that the first ECOC event organised in a transnational macro-region was in the first place about region-building and attracting large visitor numbers. The objective was to help to build a common regional identity for a functional cross-border region, i.e. to add a cultural dimension to a region of economic (notably in the form of work commuting) and political transnational cooperation.

It was however only marginal related to the issue of restructuring this former coal and steal area, which probably led to disappointments particularly in the Lorraine region. Here the lasting effects of Lille 2004 on this cross-border agglomeration had led to “enormous expectations” (‘Luxemburg and …’, 2008: 88), even though it became quickly clear that neither context nor budgets were comparable. Luxemburg and the Greater Region 2007 was also not particularly related to objectives concerning the built-up of culture or creative industries, even so such aspects were addressed.

Ruhr 2010

In 2006, the European Commission nominated “Essen representing the Ruhr” as ECOC 2010. So the event was again given to a restructuring urban region, i.e. the Ruhr region, once the economic heart of Germany and characterised by coal and steel production. In the 1990s, its restructuring process had been supported by the decade-long event of the “International Building Exhibition Emscher Park” that implemented muster and flagship projects throughout the region on topics such as brown-field site development, industrial and mining land restoration, using industrial heritage for cultural and tourist functions, creating technological incubators, or regenerating inner cities (Percy, 2008). In the logic of what was named a “one thousand flowers” revitalisation strategy, the objective was to kick-off and then sustain the transformation of the economic structure as well as the image of the Ruhr. After the final presentation event of the International Building Exhibition in 1999 local and regional actors were looking for ways and structures to keep its momentum, and the ECOC bid is to be seen as one of the results of this intention. The Ruhr with its 5.3 million inhabitants consists of 53 cities and communes that are organised in the Ruhr Regional Association, and it was this intercommunal body that launched the ECOC candidature and chose the municipality of Essen – the city in which the Ruhr Regional Association has its seat – to formally represent the bit.

So quite congruent to the main objectives of Lille 2004 (and also Liverpool 2008 or Linz 2009 since then), Ruhr 2010 was about culture-led restructuring and regeneration by projects, strengthening of the culture and creative industries base, image and tourism campaign, and integration processes in the local community. However there are two aspects worth highlighting: Firstly, the support of creative industries networks became a major issue. One of the four main themes of the ECOC event was named “city of creativity”, and the defined objective was to foster the potential of creative industries by strengthening and extending existing networks between the creative industries community in the Ruhr Region, and by supporting new initiatives (Heinze & Hoose, 2011). Numerous activities in the other main themes also supported this objective, notably urban projects within the “city of opportunities” theme and culture events within the “city of culture” theme (Mittag & Oerters, 2009: 84). The objective of supporting regional economic development had even taken the forefront to such an extent that critics started complaining about the neglect of art support. And secondly, this time the ECOC objectives were not just extended to an urban region, but actually the ECOC was an urban region.

The city of Essen (after a short period of discussion whether it should be Essen or Bochum) may have accepted the organisational burden to represent the Ruhr and thus to play a somewhat pre-eminent role in the event (e.g. Essen had a year-long cultural programme, while each of the other 52 communes was a so-called “local hero” for just one week), yet it was not its centre point. In the Ruhr 2010 association created to organise the event the decisive members were not only the city’s representatives, but equally the representatives of the Ruhr Regional Association, the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, and the body of representatives from local industrial families and companies supporting the structural change in the Ruhr Region.

Candidature Görlitz-Zgorzelec 2010

The selection of Essen representing the Ruhr as ECOC 2010 was the result of a process that originally involved 15 candidatures, of which two were finally submitted to the European Commission by the German committee. The big rival of Ruhr 2010 was the joint German-Polish candidature of Görlitz and Zgorzelec, one of the so-called twin cities on Oder and Neisse that in 1945 were divided into a German and a Polish commune as a result of the new demarcation of the German-Polish border. Even though this candidature was unsuccessful in the end, it merits some attention here as Görlitz and Zgorzelec 2010 came close to add a new regional perspective to the ECOC, i.e. a borderland dimension (Liubimau, 2009). The key motive of the ECOC candidature was to build cultural bridges between both sides and communities, and thus to contribute to the creation of a joint German-Polish (and not a German and a Polish) borderland identity. The “European City of Görlitz and Zgorzelec”(as it calls itself officially) is a theatre of close cooperation in numerous fields (and using German-Polish as well as EU funds) since the early 1990s, and it was to become the focus point of cross-border cultural interaction, and of creating a cross-border cultural identity, in the German-Polish borderland. As this is a region with a difficult socioeconomic situation on both sides of the border, leading on the German side even to the phenomenon of massive economic and demographic shrinking processes, the ECOC bit is also to be seen from the perspective of creating economic growth by increasing the attractiveness for economic activities, notably tourism, and for qualification and education offers, notably in a trans-border German-Polish and European context. Some of the projects conceived for the ECOC bit actually have been implemented, of which the reconstruction of the Old Town Bridge, offering again a direct pedestrian link between the historic centre of Görlitz and Zgorzelec, is the pre-eminent and most symbolic example.

Marseille-Provence 2013

There had been fierce competition to get the 2013 title between several French cities, and most had referred to the “success of Lille 2004” in their candidature (Paris & Baert, 2011: 34). So it comes to no surprise that both the aspect of regeneration by culture and of an extension to the urban region would play a major role in the concept of the fourth French ECOC, and finally the title was awarded to a metropolitan region, i.e. the “Urban Community of Marseille-Provence Metropolis” and surrounding urban districts. The creation of the “Urban Community of Marseille-Provence” as late as in the year 2000 was part of a multi-layer long-run policy effort to tackle the socioeconomic problems of the Marseille metropolitan area. However the territory covered by the urban community falls well short of comprising the functional agglomeration, as a number of larger municipalities in a rather favourable socioeconomic situation (e.g. Aix-en-Provence) refused to tie closer links to “trouble-ridden” Marseille, and preferred to install their own so-called agglomeration communities with their surrounding communes.

Despite this somewhat tense situation – to which added different political party belongings of mayors – the Marseille-Provence 2013 bit received early support in the whole urban region, which is why the administrative board of the management body of the event, the Marseille-Provence 2013 Association, assembled representatives not only from the city of Marseille and from Marseille-Provence Metropolis, but of six urban districts, each in turn represented by one municipality, and one further municipality. In addition, there were representatives of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur Region, of the Bouches-du-Rhône Department and of numerous public and private institutions throughout the region. In consequence it was clearly expressed that Marseille-Provence 2013 “is a regional culture project” (‘Marseille-Provence 2013’, 2008: 116).

Concerning the “Urban Community of Marseille-Provence Metropolis” as the core area of the event, defined development strategies for this area included both a general outline plan for culture and the ECOC concept itself, putting the event in the direct context of “enhancing economic growth, influence and attractiveness throughout the area”, of creating “an economy based on knowledge, innovation and creativity”, and of fostering “the growth of tourism (…) especially with regard to cultural tourism” (ibid.: 105). Accordingly a special long-run tourism development plan has been prepared parallel – and closely related – to the ECOC programme, while the ECOC bid as such was seen to be “entirely based on the territory’s desire to play a part in building a creative Europe” (ibid.: 208). In addition, the ECOC was also to constitute a continuation – in the form of the construction of new cultural facilities – of the urban regeneration policy by major urban projects. The flagship project of this strategy – started in the 1990s – is the large-scale port redevelopment project of Euroméditerranée that concerning its programme and geostrategic naming had the political objective of making Marseille a pre-eminent European metropolis in the Mediterranean region. In consequence a number of large-scale urban development projects, most of them on inner-city brown field sites, were implemented. The flagship project was the Museum of the European and Mediterranean Civilisations in Marseille, which is undoubtedly about “equipping the Marseille transformation train with a powerful locomotive of the ‘architecture-event’ type” (Rodrigues Malta, 2009: 326). So Marseille-Provence 2013 is to be seen as part of an overall redevelopment strategy for city and region, to enhance its position in the Mediterranean region and to foster creative and culture industries by networking.

Wroc?aw 2016

According to the ECOC regulations, Poland is to have its second ECOC in 2016. Poland was therefore to become the first example of staging on a grand scale a national pre-selection concourse to designate a city in a new Central European EU member country. With the obvious exception of Cracow all but the smallest voivodeship capital cities, as well as the capital city of Warsaw, submitted application documents in 2009. In the following year five of these eleven cities were shortlisted by the Polish ministry of culture, before in June 2011 the Lower Silesian capital city of Wroc?aw with around 630,000 inhabitants was proclaimed as ECOC 2016. Wroc?aw is undoubtedly one of the strongest Polish economic urban centres with a diversified economic structure. Development strategies are aiming at making the city more attractive for foreign investment, profiting in particular from the location close to the German and to the Czech border, as well as for tourists. The city’s municipality had applied twice unsuccessfully for organising the world exhibition (EXPO 2010 and 2012), however Wroc?aw was to become one of the host cities of the 2012 European Football Championship in Poland and the Ukraine, and used the event to upgrade its sport and transport infrastructure by major investments. The motivation for the ECOC candidature is to be seen from this perspective, as the event is interpreted to be “a highlight in the city’s efforts to clearly mark its place on the map of Europe” (‘Instytucja Kultury Wroc?aw 2016’, 2011: 23).

Judging from the application document, Wroc?aw 2016 is predominantly seen as a tool to attract tourists, upgrade the cultural infrastructure, refurbish the cultural heritage, and to marketing the city on an international stage. However regional aspects are rather weakly addressed. The Institution of Culture Wroc?aw 2016 as managing body is a municipal unit, and most public money in the ECOC budget will be from the city’s budget, with additional funds from the region, i.e. the voivodeship and some partner municipalities. The latter aspect refers to the fact that Lower Silesia is to represent Wroc?aw 2016’s regional dimension, yet apart from the voivodeship’s support for its capital city the application names only seven cities in that region that signed a cooperation agreement with the city of Wroc?aw, plus the Czech city of Hradec Králové and the German city of Görlitz as those were historically associated with Lower Silesia. With regard to the more critical socioeconomic situation around Wroc?aw than in the city itself, Wroc?aw 2016 seems rather to be interpreted as a chance to “revive and tighten links between Wroc?aw and Lower Silesia” (‘Instytucja Kultury Wroc?aw 2016’, 2011: 17) based on a mobilising effect of the event on the region in the fields of tourism and culture. So it is rather vaguely hoped that the ECOC event will open a chance for further regional cooperation, which perhaps – as one feels inclined to add – may include progress in the process of creating intercommunal metropolitan cooperation structures.

Quite specific however is the programme of building or revitalising urban ensembles as well as culture and heritage objects. The list includes two new major cultural objects, i.e. the National Forum of Music and the Wroc?aw Modern Museum, as well as the refurbishment of the 1913 Centennial Hall (a UNESCO World Heritage object), the modernist buildings of the 1929 “WUWA” Living and Workspace Exhibition, the famous Four Temples District, the central Market Place area, and the inner-city banks of the Odra river, and in addition the regeneration of two derelict inner-city tenement housing areas. While all of the said objects and ensembles are situated in Wroc?aw itself, regeneration works are to be extended to the region in one respect, i.e. to enhance the tourist and culture functions along the Castle and Garden Trail in the Jelenia Góra Valley. These projects reflect the general approach of Wroc?aw 2016 to concentrate on culture-led regeneration and general strengthening of the attraction of the city rather than on regional restructuring and networking.

Conclusions

As the French and the German examples reflect the ECOC has undergone significant changes. From an ephemeral culture festival (as in the case of Berlin 1988 or Paris 1989) it has evolved into a tool for territorial marketing, economic development, social cohesion and regeneration of derelict urban areas. Thus it turned into an ingredient of EU territorial development policy in times of globalisation, and consequently since the turn of the millennium the ECOC started to overstep city boundaries by first including regions, and then by regions becoming a ECOC. For this regional turn, various dimensions may be differentiated: the first facet is the metropolitan region whose centre city organises the event together with the communes and supra-local entities to which it is functionally connected.

Here the two French examples of Lille 2004 and Marseille-Provence 2013 are a point in case, and it is no coincidence that in both cases the urban agglomeration, comprising only the centre part of the metropolitan region but institutionalised in the form of intercommunal urban communities, played a major role in conceiving and organising the event. In the case of the Southern French metropolis it is even its urban community – not municipality – that officially got the ECOC title. The two said cases, together with Ruhr 2010, represent the second regional facet: the ECOC comprising a declining industrial region. Ruhr 2010 – even though it may have been represented by the city of Essen – is in effect the first example were the ECOC event was not only taken place in an urban conurbation, but actually organised by it – in form of its intercommunal Regional Association.

And in all three examples the ECOC event was used to continue and to strengthen a regeneration and restructuring process that had been started – not least in the form of urban flagship projects – decades before the event. In addition, all three examples have been strongly supported by regional self-government entities, i.e. regions and departments in France and federal states in Germany, which is the third facet. In the case of Luxembourg and the Greater Region 2007, the ECOC event even extended to a territory not defined on the communal, but on this regional level. Apart from the Duchy and the city of Luxemburg itself, the organisational structures included the representatives of regional entities. The transnational character of the Greater Region (in which four nationalities and three languages come together) leads to the fourth facet, i.e. the ECOC as a border region, of which Lille 2004 with the integration of Belgian communes was the first practical example, while Berlin 1988 at its time could not include any cross-border aspects but in the form of the political statement made by attributing the title to the divided city.

The unsuccessful bit of Görlitz and Zgorzelec 2010 would have been an example of giving the title to a borderland in the immediate sense. In conjunction with the cross-border aspect the network region may be defined as the last facet of the ECOC’s regional turn. Other than in the case of the selection of comparatively small cities – as e.g. Weimar 1999 or Avignon 2000 – the ECOC may always have had the challenge to be visible and perceptible throughout an urban space, however with the extension to a regional dimension this has become even more difficult. So the strategy to choose projects throughout a region and to link them by common themes and objectives rather than by visual and architectural means has become more sophisticated. To that adds the approach to use the ECOC event for building competence networks or clusters in the fields of culture and creative industries, which was a strong feature of Ruhr 2010, and to a lesser degree also for Marseille-Provence 2013.

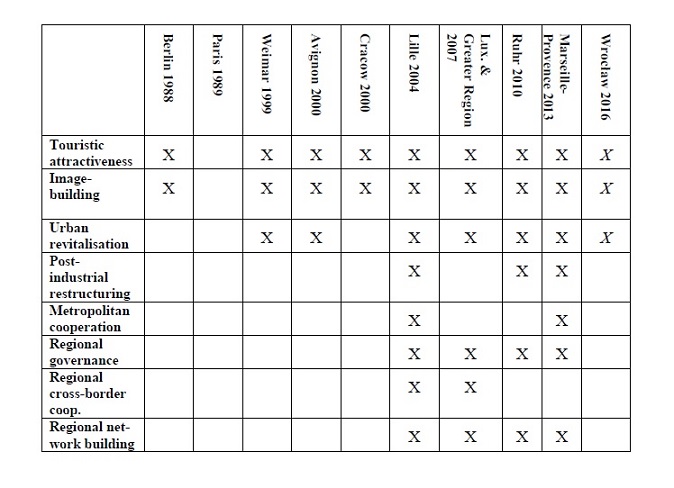

Fig. 2: Priority aspects (in addition to culture dimension) of the French, German and Polish ECOCs

Source: own compilation

When finally looking at Wroc?aw 2016 from the perspective of the French and German examples (fig. 2), it appears that this event will be rather following the footsteps of Weimar 1999 and Avignon 2000 than of Lille 2004, Ruhr 2010 or Marseille-Avignon 2013. It is focusing on image-building, tourist attraction, culture infrastructure upgrading and heritage refurbishment while – at least in its application document – somewhat neglecting economic restructuring aspects, including the potential of culture and creative industries. Wroc?aw 2016 has however clearly more ambitions than Cracow 2000, which was solely focused on city marketing and tourist figures, as it sees the event as a tool for city development. It is striking that the two ECOC in Poland – so in what for a long time had been called a transformation country – have put the least emphasis on change, while this has been the main theme in Western cases such as Lille 2004 or Ruhr 2010.

Concerning the regional dimension, Wroc?aw 2016 – apart from being supported by the voivodeship of Lower Silesia – is rather reluctant in its objectives. This may be interpreted as reflecting the general lack of cooperation between cities and their regions in Poland, especially on the metropolitan level. Judging by the application document, Wroc?aw 2016 is to enhance the competitiveness of the city rather than to support the restructuring process in the far less prosperous urban region. While it may well be argued that the process to prepare Wroc?aw 2016 is of course still ongoing, and that it remains to be seen which urban-regional dimension the event will finally have, the problem of cities in East Central Europe to respond to the requirement of building strong metropolitan regions in the understanding of EU territorial development concepts (Tölle 2013) appears to become visible also by the example of the regional turn of the European Capital of Culture.

Literature

Booth, P. and Doyle, R. (1994), “See Glasgow, see culture,” in: F. Bianchini and M. Parkinson (ed.), Cultural policy and urban regeneration. The West European experience, Manchester: University Press, 21-47.

Evans, G. (2001), Cultural planning. An urban renaissance?, London & New York: Routledge.

Gierat-Biero?, B. (2009), Europejskie Miasto Kultury. Europejska Stolica Kultury. 1985-2008 [European City of Culture. European Capital of Culture. 1985-2008], Kraków: Instytut Dziedzictwa.

Griffiths, R. (2006), “City/Culture Discourses: Evidence from the Competition to Select the European Capital of Culture 2008,” European Planning Studies 14 (4): 415-430.

Habit, D. (2011), Die Inszenierung Europas? Kulturhauptstädte zwischen EU-Europäisierung, Cultural Governance und lokalen Eigenlogiken [The orchestration of Europe? Capitals of Culture between EU Europeanization, cultural governance and local intrinsic logics]. Münster: Waxmann.

Hall, P. (2004), “European cities in a global world,” in: F. Eckardt and D. Hassenpflug (ed.), Urbanism and Globalization. Frankfurt (Main): Peter Lang, 31-46.

Hassemer, V. (1988), “Berlin – Kulturstadt Europas 1988. Das Programm und seine Organisation” [Berlin – European City of Culture 1988, The Programme and its Organisation], Zeitschrift für Kulturaustausch, 4 (38): 513-517.

Hassenpflug, D. (2004), “Germany, Weimar and the Bauhaus. A Micro-Analysis of Globalization,” in: F. Eckardt and D. Hassenpflug (ed.), Urbanism and Globalization, Frankfurt (Main): Peter Lang, 15-22.

Heinze, R. G., Hoose F. (2011), “Ruhr.2010 – Ein Event als Motor für die Kreativwirtschaft?” [Ruhr 2010 – An event as an engine for the creative industries?], in: G. Betz, R. Hitzler and M. Pfadenhauer (ed.), Urbane Events, Wiesbaden: VS, 351-368.

Hughes, H., Allen, D. and Wasik, D. (2003), “The Significance of European “Capital of Culture” for Tourism and Culture: The Case of Kraków 2000,” International Journal of Arts Management, 5 (3): 12-23.

Ingram, M. (2010), “Promoting Europe through ‘Unity in Diversity’: Avignon as European Capital of Culture in 2000,” Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Europe, 10 (1): 14-25.

Instytucja Kultury Wroc?aw 2016 (2011), Przestrzenie dla pi?kna – na nowo rozwa?one. Aplikacja Wroc?awia o tytu? Europejskiej Stolicy Kultury 2016 [Spaces for Beauty – newly considered. Wroc?aw’s Application for the title of European Capital of Culture 2016], Wroc?aw.

Keohane, K. (1999), “Re-membering the European citizen: the social construction of collective memory in Weimar,” Journal of Political Ideologies, 4 (1): 39-59.

Krätke, S., Wildner, K. and Lanz, S. (2012), “The Transnationality of Cities: Concepts, Dimensions and Research Fields. An Introduction,” in: S. Krätke, K. Wildner and S. Lanz (eds.), Transnationalism and Urbanism, New York & Abingdon: Routledge, 1-30.

Kujath, H. J. (2002), Die Logiken internationaler und nationaler ökonomischer und politischer Verflechtungen zwischen Metropolräumen [The logics behind international and national economic and political interrelations between metropolitan areas], Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 6/7: 289-300.

Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities, 2007.

Letniowska-Swiat, S. (2002), “Pratiques et perceptions d’une métropole transfrontalière: l’exemple lillois” [Practices and perceptions of a cross-border metropolis: the case of Lille], in: B. Reitel, P. Zander, J.-L. Piermay and J.-P. Renard (ed.), Villes et Frontières, Paris: Anthropos, 99-113.

Liubimau, S. (2009), “Place-Promotion and Scalar Restructurings in Urban Agglomeration on Internal EU Borders: The Case of Goerlitz-Zgorzelec,” Polish Sociological Review, 2 (166): 213-228.

Luxemburg and Greater Region, Capital of Culture 2007. Final Report 2008.

Marseille-Provence 2013, 2008. Marseille-Provence 2013 – European and Mediterranean. Application to become the European Capital of Culture, Marseille.

Mittag, J. and Oerters, K. (2009), “Kreativwirtschaft und Kulturhauptstadt: Katalysatoren urbaner Entwicklung in altindustriellen Ballungsregionen?” [Creative Economy and Capital of Culture: Catalysts of Urban Development in De-Industrialising Urban Regions?], in: G. Quenzel (ed.), Entwicklungsfaktor Kultur. Studien zum kulturellen und ökonomischen Potential der europäischen Stadt. Bielefeld: Transcript, 61-92.

Oerters, K., 2008. “Die finanzielle Dimension der europäischen Kulturhauptstadt. Von der Kulturförderung zur Förderung durch Kultur” [The financial dimension of the European Capital of Culture. From funding culture towards funding by culture], in: J. Mittag (ed.), Die Idee der Kulturhauptstadt Europas. Anfänge, Ausgestaltung und Auswirkungen europäischer Kulturpolitik. Essen: Klartext, 97-124.

Paris, D. and Baert, T. (2011), “Lille 2004 and the role of culture in the regeneration of Lille métropole,” Town Planning Review, 82 (1): 29-43.

Parysek, J. J. (2007), “Metropolitanisation from a Central-European perspective at the turn of the 21st century,” Quaestiones Geographicae, 26B: 85-95.

Percy, S. (2008), “The Ruhr: From Dereliction to Recovery,” in: C. Couch, C. Fraser and S. Percy (eds.), Urban Regeneration in Europe. Oxford: Blackwell, 149-165.

Rodrigues Malta, R. (2009), “Infrastructures et culture pour une image de ville renouvelée. Marseille et autres cités portuaires d’Europe du Sud” [Infrastructure and culture for the image of a regenerated city. Marseille and other port cities of Southern Europe], in: C. Prelorenzo and D. Rouillard (eds.), La métropole des infrastructures, Paris: Picard, 316-327.

Sacco, P. L. and Blessi G. T. (2007), “European Culture Capitals and Local Development Strategies: Comparing the Genoa and Lille 2004 Cases,” Homo Oeconomicus 24 (1): 111-141.

Sohn, C. (2009), “Des villes entre coopération et concurrence. Analyse des relations culturelles transfrontalières dans le cadre de ‘Luxembourg et Grande Région, Capitale européenne de la Culture 2007’” [Cities between cooperation and competition. An analyses of cross-border cultural relations within “Luxembourg and the Greater Region, European Capital of Culture 2007”], Annales de géographie, 3 (667): 228-246.

Sm?tkowski, M. and Gorzelak, G. (2008), “Metropolis and its Region – New Relations in the Information Economy,” European Planning Studies, 16 (6): 727-743.

Tölle, A. (2013), “Transnationalisation of development strategies in East Central European cities. A survey of the shortlisted Polish European Capital of Culture candidate cities,” European Urban and Regional Studies. Epub ahead of print 30 December 2013. DOI:10.1177/0969776413512845.