Abstract

In a fragile political and economic framework, the attention to the role that culture can play in creating the bass for the future of Europe is growing rapidly. This paper investigates the impacts that culture create in several aspects of our lives: from the social cohesion to the economic development, from the mechanisms through which culture shapes our cities to making sense of our lives through knowledge. Finally, in this paper we would like to point out the links that relate culture, economic development and intangible assets such as feeling of identity and trust.

The paper compare the evidence emerging from a recent paper commissioned by the Various Interests’ Group of the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) with the insights provided by several literature reviews and the results of specific projects dealing with culture and social dynamics.

In the first chapter, we present the study, comparing several ways to look at the phenomena involved in the process of trust building; in chapter 2 we will underline the relevance of intangible assets such as social cohesion, in Chapter 3 we will analyze, more in detail the necessity of a sustainable economic growth. Our conclusions will show how cultural interventions within the city territory can foster social inclusion, cohesion, and trust.

Introduction

Trust.

It’s difficult, nowadays, pronouncing this word without a sense of discomfort: in the day we’re writing this article, UK leaves Europe, [ while we are publishing this articles we’re counting the victims of the attack in Nice] (Editor’s Note), there is an increasing fear about IS and terrorism, there is also an increasing fear about the impact of the economic uncertainty on our daily lives.

So, how can we talk about trust? On which bases can we do it?

Indeed, we need, we have to talk about trust because of these reasons, because of these fears, and there is no way to talk about this topic but culture. (Fukuyama, 1995)

How can culture create trust?

At a more in depth look, this is not a difficult question. Culture, knowledge and memory are at the very heart of trust. Just think at your own life. You can feel a person trustworthy based on the knowledge you have about him/her, and the memory you have of what he/she did in the past, etc. etc.

At a structural level, culture can help in the process of trust building in several ways, but in this paper we would like to point out just a few that are, to our opinion, very important.

These topics could be divided into:

– Sense of Belonging and Identity

– Economic Development

These topics are deeply analyzed within a recent paper, commissioned by the Various Interests’ Group of the EESC to Agenda 21st For Culture and Culture Action Europe, a research that focuses on four main mechanisms relating culture, trust and identity in Europe. These mechanisms reflect also different point of view and different kind of interest dealing with Culture:

– Culture as a vehicle of economic growth;

– Culture as an instrument for reconverting cities;

– Culture as a tool for integration and inclusiveness;

– Culture as a pillar of European Identity within Europe and Beyond.

At a first glance, our two variables are strictly related with the four chapters of the study, dealing with the same phenomena in a different perspective. Sense of belonging relates with integration, inclusiveness and identity. Awareness is a desirable result of a set of knowledge that involves culture, history (a common history) and is, at the same time, the basis on which a sense of identity can be built. Finally, the economic development we refer to is the premise that allow a sustainable economic growth. Obviously, cities are the scenario where these mechanisms are more visible and sensitive.

Cities, indeed, are the places where change happens, and since a decade, the role that big municipalities play in the global challenge has grown significantly. However, this is not only a contemporary phenomenon: throughout European history, cities have consciously placed themselves centre-stage in our political systems (Jahier, 2016). Today, cities are becoming increasingly dominant in the social, political and economic landscape. Globally more people live in urban then in rural areas, with 54 percent of the world’s population in urban areas in 2014. (Agenda 21 for Culture – UCLG; Culture Action Europe, 2016).As the world continue to urbanise, sustainable development challenges will be concentrated in cities and more integrated policies will be needed. (United Nations, 2014)

Sense of Belonging and Identity

Trust, sense of belonging and identity are immaterial infrastructures that regulate cultural, economic and social life although they formally entered only in recent years within the economic debate (Zamagni, 2006). They represent both great objectives to achieve and useful tools to build a sense of social cohesion, that is, one of the most important goals in avoiding the escalation of act of terrors that are more and more frequent in recent days. “Cultural tools are clearly useful in speeding up the process of individual integration. In cities faced with problems including and integrating sectors of their population, agents of change are enormously valuable, especially when the built infrastructure and the manufacturing economy are in disrepair.” (Agenda 21 for Culture – UCLG; Culture Action Europe, 2016)

The role of culture as an empowering tool to foster social cohesion is a topic widely discussed in both the academic literature and the economic life. In this respect, evidence that points out the relevance emerging from projects is globally widespread.

Scottish Government recognize that an “Australian longitudinal example found that community-based arts activity developed feelings of identity and confidence in the community” (Ruiz, 2004), while Africalia’s experience allows us to point out the role of artists as agents of social change and inclusion (International Congress on Culture and Sustainable Development, 2013).

There are also strong evidences proving that “promoting cultural diversity in national and international policies fosters social inclusion and equity, (UNESCO). These evidences emerge from projects involved in supporting social cohesion through culture and arts in Latin American cities (Interarts, 2016), and on the other hand, it has been demonstrated that in Russia “social cohesion […] is shown to be conducive for economic development, institutional performance, and quality and governance”. (Menyashev & Polishchuk, 2012)

Furthermore, “among the challenges cities face, few are greater than finding the right tools to foster inclusion” (Agenda 21 for Culture – UCLG; Culture Action Europe, 2016), and the report recently commissioned by EESC envisages three distinct areas of interest: the intercultural dialogue and migration, gender topics, and the special needs emerging from different kind of disability.

Recent news sections and events highlight how pertinent could be the relevance of these topics, and the urgency we need to create solutions to bridge out the different cultures that live in our territory. In this sense, we are invited to understand our need in creating an equilibrium based on cultural diversity, it doesn’t matter how fragile could be, should be a priority for the future of Europe and the Member States: “As a source of exchange, innovation and creativity, cultural diversity is as necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for the nature.” (UNESCO, 2002)

Cities are the place where this cultural diversity should flourish and this process involves at the same level government, regions and mayors. Several efforts have been made in order to create a territory in which the cultural differences could be view as a key development factor. In facts, “social cohesion is valued not only because it may have certain developmental and economic implications but also because it has intrinsic value too”. (Pervaiz, Chaudhary, & Van Staveren, 2013).

It is in this direction that most international cities are working on, following a double strategy: on one hand there is an even growing interest about intangible assets; on the other hand, this interest matches with the necessity to renew material infrastructure (road, railways, etc.) (Landry, 2006)

This common interest created in last decades a great set of interventions (Bianchini & Parkinsons, 1993), and a great awareness that pushed up both the number and the quality of structural-intangible asset renewal. (DETR; CABE, 2000) Meanwhile, the establishment of the specific cluster of Cultural and Creative Industries (Commissione Europea, 2010) shown with more strength how a cultural driven economic model could represent a great opportunity (British Countries Creative Industries Unit, 2004) for the transition from an industrial economy to a service economy (Waterfront Auckland, 2014). This led the debate to a still unresolved question: the measurement of the impacts of cultural and creative industries in the overall economy (Ernst&Young, 2014) (Eurostat, 2016) (The Learning Museum, 2013).

The Economic Growth

The economic impact of cultural interventions (whether they’re included in the CCI cluster or not) remain a question point that needs a general incontrovertible answer. There is, indeed, a huge amount of studies, researches and reports investigating this report, but there is a lack of shared data-sets (Eurostat, 2016), and indicators (Monti S. , Bernabè, Casalini, & Quadrelli, Cultural Accountability – Una questione di Cultura, 2015).

The reason is obvious; culture provides relevant impacts in almost every aspect of the economy: from the interpersonal relationship (Casalini & Tavano Blessi, 2013) to the brand image of entire nations (Monti S. , Bernabè, Casalini, Marchese, & Stuto, 2014). Therefore, creating a set of indicators and statistical variables able to combine the different impacts within a specific territorial area is a task of most relevant in the near future.

We do have statistical reports, proxies and very accurate analyses, but, most of times they refer to data-sets that are obsolete, or different from each other. Neither at the Country nor at the Union level, there are sets of specific variables that allow us to share and compare data emerging from different experiences.

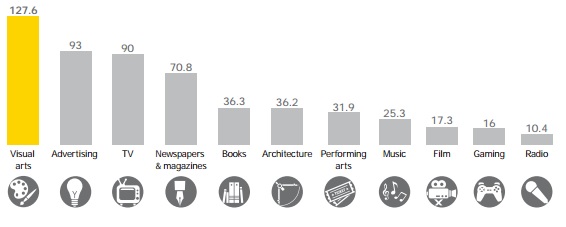

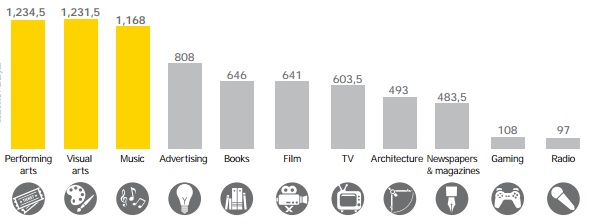

One of the most recent reports published by Ernst&Young (Ernst&Young, 2014) indicates facts and figures about CCIs in Europe. Following this report, CCIs contribute to 4.2% of Europe’s GDP, with revenues of € 535,9 billion and with more 7 millions of Europeans directly employed in creative and cultural activities.

In 2006, following KEA (KEA European Affairs, 2006), the Cultural and Creative Sector generated a turnover of more than € 654 billion, contributing to 2.6% of European Union GDP, employing 5.8 million people (equivalent to 3.1% of total employed population in EU25).

The impacts the entire sector generates both directly and indirectly are, probably, bigger than this: the reports do not take into account several variables. Among others the reports do not take into account the real estate impact of cultural institutions (Center for Creative Community Development, 2010), the community integration deriving from cultural consumption (Huang & Liu, 2016), the influence on the export (Bernier, 2005) and the impacts of mega-events (Matheson, 2006) (Mûller, 2015), as well represented by Olympic Games, Universal Expositions and the European Capitals of Culture.

Despite this debate, however, the role of economic impacts is by now fully acknowledged. In the case of European Union, to date, the political dimension of Culture has been understated and subtle. The Treaties clearly defend the principle of subsidiarity. Article 167 of the TFEU states that “The Union shall contribute to the flowering of the culture of the Member States”. Nonetheless, it adds that “at the same time [it will bring] the common cultural heritage to the fore”.

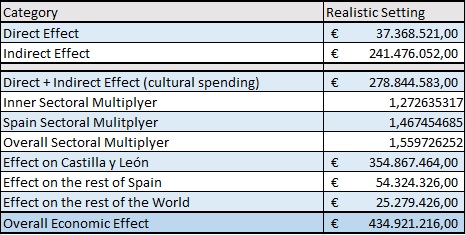

More in detail, as quoted in (Agenda 21 for Culture – UCLG; Culture Action Europe, 2016), there is a useful analysis of the estimated impacts of 2002 Salamanca European Capital of Culture (Herrero, Sanz, Devesa, Bedate, & del Barrio, 2006). In that paper, authors highlight the dimension of the importance of the three main domains of any cultural intervention: direct, indirect and induced effects.

Analyzing the expenses and the added values produced during the period 2010-2012, and using the Input-Output matrix in order to establish the multiplying effects, authors establish the overall economic effect in € 434.921.216,00.

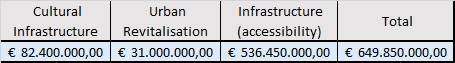

For comparison, the bidding book of Matera 2019 indicates in the preliminary budget infrastructural investments for € 649.850.000,00

Once again, the place where culture is showing its main impacts is the urban territory. Cities today are looking for new paradigm to foster their economic and social development, and all the most important framework implies willy-nilly the cultural phenomenon: in a few decades the paradigm shifted from the creative (Landry & Bianchini, 1995) to the Sharing City (McLaren & Agyeman, 2015).

In this scenario, particularly interesting are the experiments of cultural-led urban renewal. In facts this kind of operation has generated in few years a great variety of innovation both in the governance and in the management of cities.

With specific regards to the urban renewal phenomenon, some authors highlighted the relevance of culture as an empowering tool (Monti & Casalini, Empowering Culture) for society, borrowing the definition of empowerment as indicated by Rappaport (Rappaport, 1981).

Furthermore, several authors point out that urban renewal phenomenon, one of the most important approaches of culture within the urban territory, could be historically related to dimensions of social control, even if in its recent implementations the evidence of such a social control is less visible then it was used to be. (Le Galès, 2002)

Finally, culture-led urban interventions are able to redefine both the built environment and the intangible assets that characterize specific areas, streets or neighborhoods, enabling, sometimes, the setting up (or the reconstruction) of local economies.

Creating wealth, or at least, re-establishing the normal conditions of a market economy, is a crucial aspect of the complex way we can look at the cultural phenomena today: knowledge, awareness, identity, social inclusion and cohesion are at the very heart of the future and the development of our Europe, but in order to build a sense of common trust, a peculiar attention to the economic lifestyle of citizen is needed.

Conclusions

In this paper we tried to explore the great challenges culture is dealing with, as well as the need for a better recognition of the extremely wide and eclectic series of impact that culture can generate in our economic and social scenario.

In doing so, we compared different approaches and several studies and reports made in last years, with a specific focus on the report recently commissioned by the Various Interests’ Group of the EESC in order to establish in which ways culture can lead us in a more sustainable Europe.

European Union is facing hard periods (the menace of terroristic attacks, the Brexit, etc.) and there is a growing need of new injection of trust.

Culture could be, should be, one of the most important tools to create social cohesion, trust, economic development and growth.

There are also growing interest and awareness about the role that culture can play within this scenario, and the recent work of the Various Interests’ Group goes in this same direction, pointing to the inclusion of the development of culture as one of the pillars for a sustainable development of the Union.

There still are difficulties in order to fully acknowledge the power of culture as well as culture has an enormous untapped potential. Our role, in this process, is to create even more opportunity, even more insights and evidences, in order to achieve a shared definition of the impacts that culture generates within the territories and the citizenship.

Our goal is to show that trust is one of most important intangible assets on which build a stable and sustainable society. Europe should look at the future through cultural perspective. It’s on us (politicians, academics and economic investors) the duty to carry on this view. We got the tools to make it possible. We will able in doing it.

References

Agenda 21 for Culture – UCLG; Culture Action Europe. (2016). Culture, Cities and Identity in Europe. Bruxelles: European and Social Committee.

Bernier, I. (2005). Trade and Culture. In P. F. Macrory, A. E. Appleton, & M. G. Plummer, The World Trade Organization: Legal, Economic and Political Analysis Volume I (p. 2331-2378). United States of America: Springer Edition.

Bianchini, F., & Parkinsons, M. (1993). Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

British Countries Creative Industries Unit. (2004). Creative Industries. British Council.

Casalini, A., & Tavano Blessi, G. (2013). Cultura, Beni Relazionali e Benessere. In E. Grossi, & A. Ravagnan, Cultura e Salute. Milano: Springer-Verlag.

Center for Creative Community Development. (2010). Brief Summary of the Economic Impact of MASS MoCa in Berkshire County, MA. Center For Creative Community Development.

Commissione Europea. (2010). Libro Verde – Le industrie culturali e creative, un potenziale da sfruttare. Bruxelles.

DETR; CABE. (2000). By Design; Urban Design in the planning System: toward better practice. Department of the Environment, Tansport and Regions.

Ernst&Young. (2014). Creating Growth – Measuring Cultural and Creative Markets in the EU. Ernst&Young.

European Union. (2001). Green paper – Promoting a European framework for corporate social responsibility.

Eurostat. (2016). Culture Overview. Tratto da Eurostat: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/culture/overview

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Penguin Books.

Herrero, L. C., Sanz, J. Á., Devesa, M., Bedate, A., & del Barrio, M. J. (2006). The Economic Impact of Cultural Events – A case study of Salamanca 2002,

European Capital of Culture. European Urban and Regional Studies, 41-57.

Huang, X., & Liu, X. (2016). Consumption and Social Integration: Empirical Evidence for Chinese Migrant Workers. Economics.

Interarts. (2016, January). Culture and Arts Supporting Social Cohesion in Latin American Cities. Tratto da http://www.interarts.net/en/encurso.php?p=445

International Congress on Culture and Sustainable Development. (2013). How does culture drive and enable social cohesion and inclusion? Hangzhou: People’s Republic of China.

Jahier, L. (2016). Inaugural Speech. A Hope for Europe. Bruxelles: European Economic and Social Committee.

KEA European Affairs. (2006). The Economy of Culture in Europe. Bruxelles: KEA.

Landry, C. (2006). The Art of City Making. EarthScan.

Landry, C., & Bianchini, F. (1995). The Creative City. London: Demos Comedia.

Le Galès, P. (2002). European Cities. Social Conflict and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Matheson, V. A. (2006). Mega-Events: The Effect of the world’s biggest sporting events on local, regional, and national economies. College of the Holy Cross, Deparment of Economics, Faculty Research Series.

McLaren, D., & Agyeman, J. (2015). Sharing Cities – A case for Truly Smart and Sustainable Cities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Menyashev, R., & Polishchuk, L. (2012). Social Cohesion, Civic Culture and Urban Development in Russia. OECD Working Paper.

Monti, S., & Casalini, A. (s.d.). Empowering Culture.

Monti, S., Bernabè, M., Casalini, A., & Quadrelli, F. (2015). Cultural Accountability – Una questione di Cultura. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Monti, S., Bernabè, M., Casalini, A., Marchese, R., & Stuto, G. (2014). Italia. Brand e Destinazione. (S. Monti, A cura di) Napoli: Graus Editore.

Mûller, M. (2015). The Mega-Event Syndrome: Why so Much goes Wrong in Mega-Event Planning and What to do about it. Journal of the American Planning Association.

Pervaiz, Z., Chaudhary, A., & Van Staveren, I. (2013). Diversity, Inclusiveness and Social Cohesion. The Hague: Institute of Social Studies.

Rappaport, J. (1981). In Praise of Paradox: A Social Policy of Empowerment Over Prevention. American Journal of Psychology, 1-25.

Ruiz, J. (2004). A Literature Review of the evidence base for culture, the arts and sport policy. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Education Department.

The Learning Museum. (2013). Report 3: Measuring Museum Impacts.

UNESCO. (2002). Universal Declaration of Cultural Diversity. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

UNESCO. (s.d.). Culture: A Driver and Enabler of Social Cohesion.

United Nations. (2014). World Urbanization Prospects (Revisions). Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Waterfront Auckland. (2014). Urban Regeneration Delivery and Funding Models. Auckland: Waterfront Auckland.

Zamagni, S. (2006). L’economia come se la persona contasse: Verso una teoria economica relazionale. Forlì: Università di Bologna.