“To the Congregation of the Oratory in Naples 250 ducati and for you, Dionisio Lazzari, at completion 1000 ducati as this much you have spent for marbles, mother of pearl, precious stones and more and in labor to build the steps with the pedestals for the High Altar of the church. 9 September 1654”

This is the transcript of an old credit certificate (Bancale) and its reason of payment, one of the documents preserved in one of the biggest archived collection of bank items that exists in the world and that dates back to 1573 up to our days, it is held in the Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli [1].

For many years this Archive has been frequented by archivists, students and researchers of economic and financial history, a magical place however, difficult to access, example of a lack of knowledge that characterizes the urban experience of Naples. An inaccessible place, just like madhouses, prisons and factories during modern times, finally retired and refurbished, with the construction of common use goods.

At 9:30 am of 10 June 2017, a group of people equipped with smartphones gathered outside the Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli to participate in the first digital Treasure Hunt of the Bank.

The Archive

The Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli is in via dei Tribunali in Palazzo Ricca that dates back to the 1500s and in the nearby palazzo Cuomo, where the ancient Bank of the Poor used to be and that now houses the Banco di Napoli Foundation. In the heart of the city, with about 330 rooms and eighty kilometers of shelving, millions of banking documents are collected and catalogued dating back from the mid 1500s to today. The Archive contains documents and news that tell the economic, social and artistic story of the south and the documents can reveal the structure and the evolution of the credit institutions of this region, along with the trade deals with other European countries.

At the beginning of the 1500, Naples was the second European city after Paris; its commercial port was one of the biggest on the Mediterranean. The streets were filled with noblemen, tradesmen, seamen and also a lot of people who survived by occasional and daily labor, often resorting to usury to satisfy primary needs. This is how the first charity organizations started, in an attempt of helping the weaker citizens escape usury.. Between 1500 and 1600 eight public Banks were established in the antique centre of Naples. As the years went by the Banks started accepting money as deposits and in turn used them to provide loans with interests, eventually converting in credit institutions. The charity institutions became richer and, to compensate the lack of money circulation, created the Bancali (certificate of deposit also known as ‘fede di credito’).

These transcripts of money deposited could be endorsed to private people or to the State and would contain a reason of payment. The certificates became a public act and started in part to replace coins. The State would use public banks to finance wars, pay supplies of food for the population, fund public works, while the poor would use them to pawn their goods; the rich, on the other hand, would simply deposit their money and treasures.

The Bancali thus became the ancestors of our modern bank checks.

For many years the Archive has been the exclusive place of reference for those who attempted to rebuild the economic history of the south of Italy by reading the Bancali.

Recently, after a change in leadership in the Banco di Napoli Foundation, the Museum of the Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli has been opened, with a project named “ilCartastorie”, with the scope of promoting the enormous heritage of stories and characters preserved in the transcripts of antique neapolitan public banks.

ilCartastorie, utilizing every communication channel available, from multimedia to creative writing, has returned to the city and the entire world the voices, the history and the stories collected in the numerous pages of the volumes held at the Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli. This activity, that started in 2015, has allowed the Museum of the Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli, with the project “ilCartastorie: the archives narrate”, to win the Prize of the European Union for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Awards 2017, awarded by the European Commission and Europa Nostra, and later in 2017 the Financial Cultural Heritage (FCH) prize awarded by the International Federation of Finance Museums (IFFM), in addition to the Cultura + Impresa 2016 prize.

Within the activities promoted by the Museum, in collaboration with Mappina – alternative map of the city [2] , the program Treasure Hunt has come to life.

The Hunt: from the Archive of the city to the Archive in the city

The Treasure Hunt of the Banco is a digital hunt that through use of the writings has brought the Historical Archive of Banco di Napoli in the city and the city in the Archive.

Through the mobile app “passAPPress”, that in neapolitan means “move onto the next one”, the participants walked through the historical centre of the city following the hints contained in the reason of payment of the Bancali, used as missions and narrated guides of the city. The reasons of payment of the Bancali explain why the Bank has to pay, from someone (“to the congregation of the Oratory of Naples 250 ducati and for you), to someone (Dionisio Lazzari) for working on something (the High Altar). This is how congregations, noblemen, abbesses, commissioned Dionisio Lazzari, Giovanni Lanfranco, Cosimo Fanzago, Ferdinando Sanfelice, artistic works of high value: altars, busts, paintings, spires, portals, enhancements and decorations of noble palaces and churches. Every certificate is like an urban story that becomes the mission that leads you through the city following the stages of an urban story that develops between 1637 and 1771 (these are the dates of the certificates used) and (re)discover the incredible urban heritage preserved by the Archive. Playing and using the Bancali as exploration missions the Hunt has brought outside the walls of the Foundation, in the city, the contents of the Archive, encouraging the participants to learn and recognise the role of the Foundation in the south of Italy thanks to the stories told in these ancient financial documents.

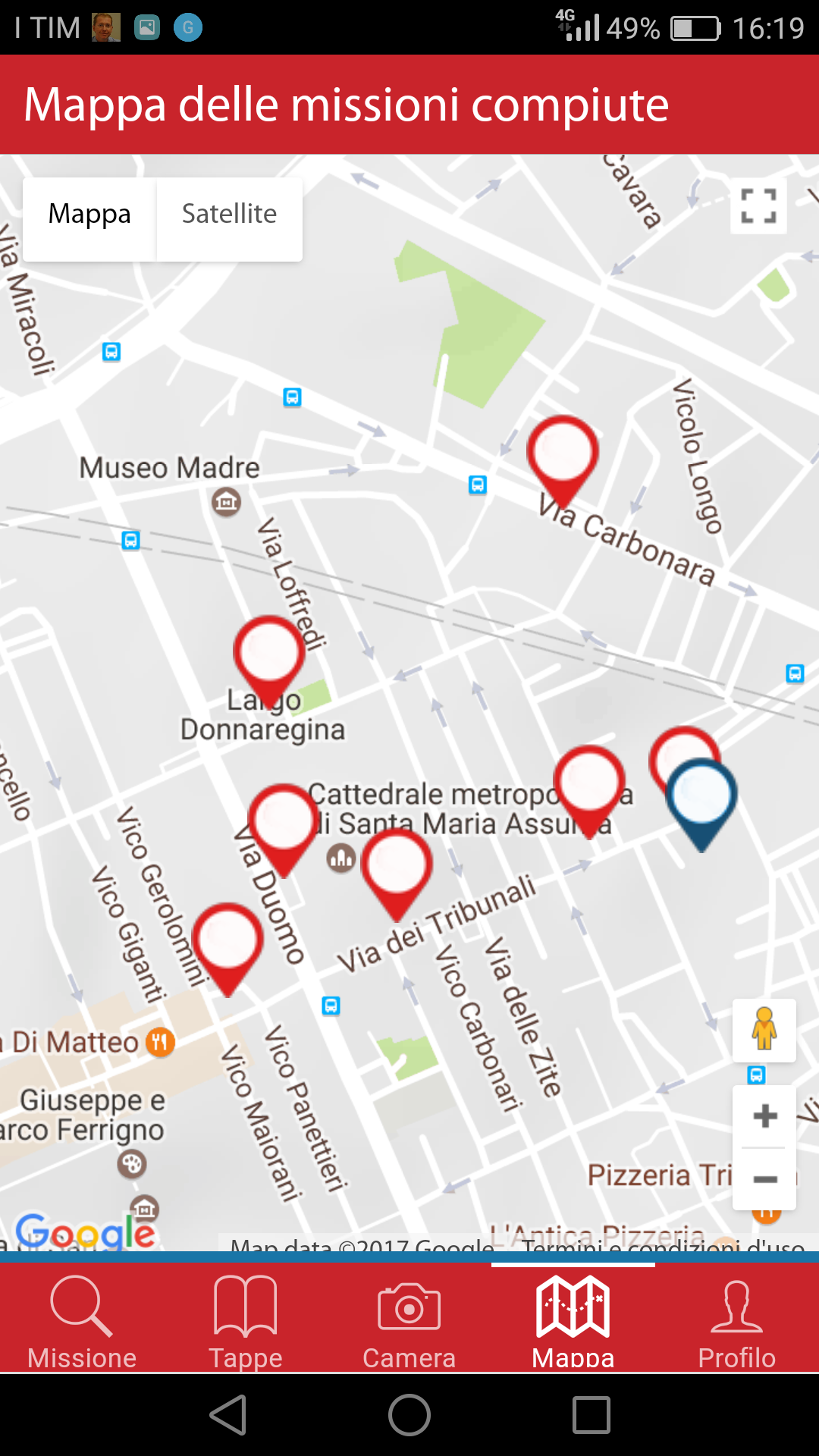

Once installed the app “passAPPress” (developed for iOS and Android smartphones and tablets), the participants, using the image and information on the certificate had to identify the place of the reason of payment. Every certificate is a mission to accomplish, stages achieved, and each time a notification appears on the app providing the content of the next mission. The participants, organized in groups, were able to explore the city using the missions and the “hints” contained in the reason of payment and, collecting evidence in the shortest time possible. All the missions accomplished progressively appeared on the digital map of the mobile app providing the routes the various groups covered during the Hunt.

Between a stop and next one, as the hunters passed by the places where one of the old Banks was located, a message would appear on their device telling the story, through images and text, of that particular Bank.

To make the competition more complex, to stimulate the group dynamics and discourage copycats, some missions were accessible through quizzes with close ended questions that asked the group about the history of the Archive and the Banco di Napoli Foundation. To make the competition more complex, to stimulate the group dynamics and discourage copycats, some missions were accessible through quizzes with close ended questions that asked the group about the history of the Archive and the Banco di Napoli Foundation.The Hunt ended at the Foundation, with the award of the prize to the winning group and the visit to the archive by all the participants.

Gamification as a tool of audience development

The Treasure Hunt was projected as a dynamic and strategic tool to reach a wider and more diverse audience for the Archive and, with the objective of generating greater active engagement of the participants, we worked on a variety of involvement and engagement tools [3] .

In particular, the financial documents of the Archive were used as tools to tell the story of the city. The objective of amplifying the audience of the Archive was achieved by involving the citizens not as receivers of the culture but as experts of the city. In this way, the desire to stimulate the city to enter the archives became its opposite: bring the archive in the city, encouraging the citizens to recognize and reinterpret the history through the documents, that are witnesses of its changes through the reasons of payments. Although the city, at times, is considered a petrified archive of its history, the hunt used the documents in the archive as narrative instruments of exploration, diffusion and sharing of the knowledge.

The knowledge the participants had of the city blended with the information contained on the documents from the Archive and with the history of the Archive itself. The Hunt ended with a visit to the Archive, giving back to the participants a material sense to their mission: the way the Bancali were used, transcribed and archived, the stories told in their reason of payment with the life and functions of the antique Banks spread around the city.

After the Hunt many participants expressed their admiration for the portal of Palazzo Ricca on via dei Tribunali dated back to the 1500s, they read about the tag that marks the home of the Foundation, admitted to peaking beyond the gates, and that although they knew of the Archive, they had never entered it.

To involve this new audience we addressed a group that had an average knowledge of digital equipment. Citizens who have some basic knowledge of the digital tools and could use “with ease and critical spirit the information technology for work, free time and communication”, no special technological ability was required.

Experimenting with new forms of involvement through digital media, we exploited mobile applications and gamification as a tool that could generate interest in an audience that was potentially interested in the archive but still extraneous to it.

We addressed an audience with digital skills that are of common use that we could productively involve in a game that would stimulate their own knowledge of the history of the city, promoting self-organization and using the competition as a game with a positive outcome, of enrichment for all the participants.

Dividing the players in groups that possibly didn’t know each other, for example, allowed the participants to research an active role in the competition: either by using the app “passAPPress”, reading and interpreting from ancient Italian the reasons of payment that contained the hints for the missions, or by searching the internet for the names of the artists related to the churches, monuments, buildings or old urban names, others searched for the shortest way to reach their destination, someone else would read the history of the archive searching for dates, places and events in an attempt to answer the questions of the quizzes.

Exploiting the opportunities offered by the new digital culture, the Treasure Hunt was a tool of urban gamification that reduced the “activation costs” to involve an audience that was potentially interested in the Archive and allowed us to create value through the interaction and fertilization between virtuality and reality, ancient and contemporary, the archive and the city. Utilizing the digital and self-organization abilities of the participants, their expertise or lack of, we stimulated an offline experience from their online interaction, discovering only at the end of the Hunt, the treasure, hidden up to that point, inside the Historical Archive of the Banco di Napoli, with its enormous heritage.

Footnotes

[1] http://www.fondazionebanconapoli.it/archivio/

[2] Mappina is a Cultural Association that promotes MappiNa – Alternative Map of the Cities, an urban communication platform built through collaborative mapping and aimed at creating a different cultural image of the city through the critical and operative contribution of its citizens.

www.mappi-na.it/

[3] For audience development refer to A. Bollo “50 shades of audience and the challenge audience development” (“50 sfumature di pubblico e la sfida dell’audience development”) found in F. De Biase (by), The audience of culture. Audience development, audience engagement, Franco Angeli, Milano, 2014